The language of sustainability professionals changed in 2020.

To continue reading, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

New words and phrases became common parlance as sustainability folk tried to make sense of one of the most calamitous years of the 21st century.

Not all of the words in this list are new to the sustainability dictionary. Some have grown in popularity with the dominant social and environmental themes of the year. Most are coronavirus-related. Some describe the state of the climate, biodiversity and equality in a year that started with forest fires, and was interspersed with growing pandemic-induced public concern over the plight of the natural world, and the killing of an African American by a policeman that set off a global movement against racial injustice.

As people and companies searched for the right words to describe themselves, not everyone managed to avoid drinking the kool aid. In a corporate blurb, one multinational nutrition firm told Eco-Business last month: “As a purpose-led, performance-driven, science-based company, we marry scientific expertise and innovative power to develop sustainable, scalable solutions.”

Here are some words and phrases that rolled off the tongues of the sustainarati in 2020:

Virus-washing

McDonald’s separated its iconic golden arches logo supposedly to show solidarity with people practising social distancing. Image: Advertising Age

The pandemic has provided an irresistable, year-long platform for companies to talk about how much they care. McDonald’s wasn’t the only company to be accused of virus-washing this year, when the fast food giant divided its golden arches logo to show solidarity with the need to social distance.

Build back better

First used at a United Nations conference on future disaster avoidance in 2015, the term became popular this year as the rallying cry of US presidential hopeful Joe Biden, who promised economic recovery for the millions of unemployed Americans if he won the White House, and to take on racial injustice and climate change at the same time. Since then, politicians and business leaders all over the world have been using the phrase (some preferring “green recovery”, another popular buzzword in 2020), promising citizens and consumers a brighter, more sustainable future. South Korea is among the few Asian countries to make sustainability central to economic recovery plans.

Shecession

The uneven impact of the global economic downturn on women. Unlike the 2008/2009 global financial crisis, which disproportionately impacted men, the pandemic-induced economic contraction has been harder on women, noted C Nicole Mason, president and chief executive of the Institute for Women’s Policy Research in the United States. She used the term “shecession” to describe a recession that was hurting predominantly non-white, females in the US. Globally, the pandemic has hit young, low-income families the hardest, particularly in countries reliant on global trade, tourism, commodity exports, and external financing. Among the hardest hit sectors in Southeast Asia has been recycling, with a contraction in trade in recycled goods all but wiping out jobs for millions of informal workers.

Net zero

In July, United Nations secretary-general António Guterres said in a speech to Tsinghua University that there was “no excuse” for humanity to fail to limit global warming to 1.5ºC, which means the world must achieve net-zero emissions before 2050, and cut emissions by half by 2030. That speech, and the UN’s Race to Zero campaign, has prompted more than 100 countries and 1,500 companies worth US$11.4 trillion to make net-zero promises. Net zero has replaced carbon neutral as the more popular term.

Sanitary cities

Social distancing circles in Domino Park, Brooklyn, United States. Image: Marcella Winograd/Wunderman Thompson

The pandemic prompted city planners to think about how to redesign cities to protect the health of residents and support “sanitary lifestyles”. In the Italian town of Vicchio, squares were painted in the town centre to help people social distance in public, while in Domino Park in Brooklyn, white circles on the grass indicated the safe distance for people to keep physically apart.

Nature-based solutions

Talk about how to combat climate change and reduce greenhouse gas emissions by burning less fossil fuels has dominated conversations about how to avert planetary catastrophe, with little thought spared for environmental conservation — until 2020, when the business world started talking more about using natural ecosystems to curb emissions. In Singapore this year, a plan is hatching to use nature-based solutions to lay the foundations for a carbon credits market.

Woke

A word that until recently meant being aware of and responsive to social and racial injustice, is now more likely to signifiy pretentiousness and cultural elitism, opined the Guardian in January. First used by African American communities in the 1960s, woke experienced a resurgence on the back of the Black Lives Matter movement and entered the Oxford Engish dictionary in 2017. But in 2020 woke shifted “from virtue signal to dog whistle” for the self-righteous.

Carbonomics

In a year of net-zero targets, carbonomics was used in conversations about the cost of decarbonisation. Popular in environmental, social and governance investing circles, it was used this year by Bloomberg for its Future of Energy show and Goldman Sachs in its The Green Engine of Economic Recovery report.

Biocontributive (or regenerative)

Consumers increasingly want to buy into brands with the smallest possible environmental footprint, but brands are increasingly saying that they can do better — by restoring the resources they use. Biocontributive, regenerative or carbon-positive brands are now in demand, and go one step further than companies talking about carbon offsetting and carbon neutrality. Agriculture and tourism were the two sectors that talked most about regeneration in 2020.

Climate (or planet-based) diets

The first thing anyone can do to reduce their impact on the planet is eat differently. Climate diets are now a thing, with eating less meat and drinking less coffee well thought of among climate-minded dieticians. A study in January found that half of American consumers say they don’t eat meat for environmental reasons, and one in five millennials have changed their diet to shrink their environmental footprint.

The perfect earth-friendly diet depends on where you live, according to a study by World Wide Fund for Nature, Bending the Curve: The Restorative Power of Planet-Based Diets. The report comes with a calculator that works out the best “planet-based” diets for each country. In Sweden, if everyone ate less meat, emissions would fall by half. In Indonesia, if everyone had enough to eat, emissions would inevitably rise regardless of the type of food consumed.

Agritourism (or agrotourism)

For people who have little regular contact with the countryside, agrotourism teaches city folk about life on a farm, and how the food they eat is grown. This increasingly popular vacation option could be a lifeline for struggling tourism and hospitality businesses. Banyan Tree Hotels & Resorts pivoted to agrotourism in June by partnering with a boutique farming collective to open an organic farm in Thailand.

Genderless fashion

Genderless fashion by Lacoste. Image: Lacoste

Gender equality was no longer enough in 2020. So the fashion business has started designing clothing that is gender neutral, genderless, or gender inclusive. “People don’t want to be defined by what someone tells them is right for them or isn’t,” said Chris Walsh, UK vice-president of sportswear brand Adidas, in an interview with Vogue this year. “It used to be that pastel colours were very gender-specific, but we don’t see that anymore. We just produce the best shoes and allow people to adopt them however they want to.”

The isolation economy

Social distancing and lockdowns have spawned a trade in services that keep people productive and entertained while stuck at home. But those same forces have also brought about mental health issues such as increased aggression towards unfamiliar people, loneliness, low self-esteem, and fear — a payday for psychologists.

Guerilla gardening

A guerrilla garden in Los Angeles. Image: Umberto Brayj

In a year when more people than ever worried about how to feed themselves, guerilla gardening — the cultivation of plants (usually edibles) on land that the grower does not own — returned to vogue. In countries such as land-scarce Singapore, there were even calls for military land to be turned into edible forests. Food security was a matter of national security, conservationists argued.

Intentional communities (or eco enclaves)

For those who have the means of escape, intentional communities have become in-demand places to move to this year. Not to be confused with communes, intentional communities are towns built with a specific spiritual or political beliefs in mind. Many have sustainability, wellness, and land conservation as guiding principles. For instance, the town of Serenbe in the United States was constructed near a woodland, houses are built using a traditional form of Japanese carpentry, and organic farms grow native crops. In recent years, the number of intentional communities, or eco enclaves, has ballooned globally to more than 1,200, according to the Foundation for Intentional Community, a non-profit that supports these experimental towns.

Bee-washing

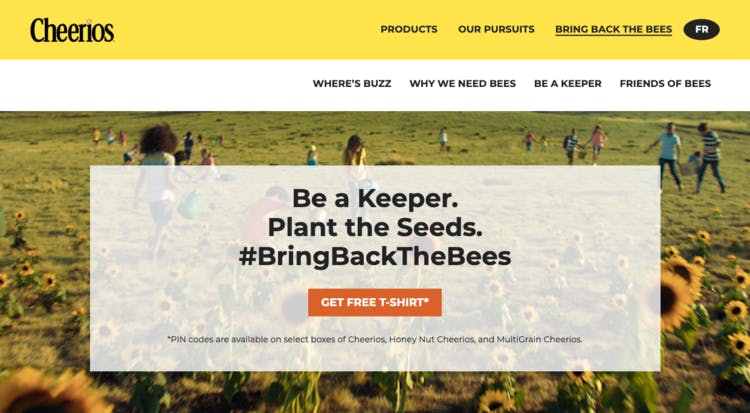

This is an example of bee-washing by cereals brand Cheerios, according to bee-washing watchdog, bee-washing.com.

The decline of an animal hailed as the most important living thing to humanity has not been lost on brands with an eye for environmental issues that generate buzz. Albert Einstein once said that if bees disappear, humans would have four years to live. Seventy per cent of the world’s agriculture depends exclusively on bees, but bee populations have plummeted as a result of deforestation and the uncontrolled use of pesticides. Latching on to this problem, companies in Europe and the United States have started to claim their products are bee-friendly or run CSR programmes to “save the bees”.

Have we missed any? Let us know by writing to news@eco-business.com. This story is part of our Year in Review series, which journals the stories that shaped the world of sustainability in 2020.