1. What is COP21?

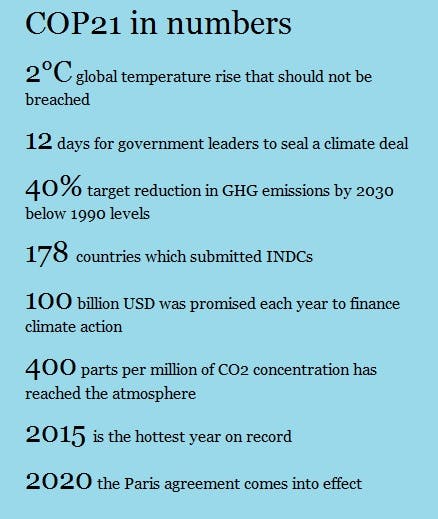

From November 30 to December 11, representatives from almost 200 nations will gather in Paris for the 21st Conference of the Parties or COP21, under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change.

To continue reading, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

COP21 will be the 21st conference since governments started meeting annually in 1995 to coordinate government efforts to tackle climate change. The first meeting was held in Berlin, Germany. At COP21 in Paris, governments will seek to make history by achieving the first ever universal agreement on climate change.

2. Why is it important?

The main objective of the meeting is to ink a global treaty for nations to collectively reduce their greenhouse gas emissions.

Scientists have pointed to excessive emissions of these gases such as carbon dioxide and methane - released from the burning of fossil fuels for energy production and destruction of forests, for instance - as the main contributor to global warming.

Some groups continue to question the link between such human activities and higher greenhouse gases in the atmosphere. But agencies such as the United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and the UN’s World Meteorological Organization have shown that global warming has been accelerating since the Industrial Revolution started in 1760. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s (IPCC’s) 2013 AR5 report also found that “the warming of the climate system is unequivocal”.

If nothing is done to curb emissions, the rise in global temperatures could exceed what is considered the “safe” threshold of 2 degrees Celsius and lead to devastating changes in weather patterns and rising sea levels.

Over the past decade, millions of people have suffered the devastating impact of numerous climate-related events: Hurricane Katrina in the United States in 2005, Typhoon Haiyan in the Philippines in 2013, as well as the the debilitating drought in California and the unusually strong El Nino this year.

3. What have governments been doing all this time?

Governments and civil society organisations worldwide have been working for decades to address climate change. In fact, it has been 50 years since the threats of climate change were raised by scientists.

But formal negotiations among governments started only after the Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil in 1992, which eventually led to the formation of the UNFCCC. All nations signed a UNFCCC treaty, agreeing to establish a framework for negotiating specific international treaties, or protocols, that may set binding limits on greenhouse gases.

They also agreed to report on their progress in reducing their emissions.

In 1997, the first global treaty on climate change was signed in Kyoto, Japan. The Kyoto Protocol mandated industrialised regions such as the US and Europe, responsible for most of the pollution, to reduce their emissions. The goal was to reduce emissions by 5 per cent by 2012 from 1990 levels - an amount deemed necessary to prevent further warming.

In 2009, the UNFCCC attempted to negotiate a universal agreement at COP15 in Copenhagen, Denmark. This highly-anticipated event failed to reach a consensus as developing nations refused to agree to emissions targets while developed nations were accused of not pulling their weight.

Instead, a Copenhagen accord was presented by world leaders on the last day of the summit, recognising the need to limit global temperature increase to 2 degrees.

As a response to criticism that rich countries’s economic activities in the past were responsible for climate change, a US$100 billion Green Climate Fund was set up for developing countries by their developed counterparts.

Over the succeeding years, governments set the roadmap for a legally binding climate deal to be formally negotiated in 2015. This is scheduled to take effect in 2020.

4. What sort of agreements are expected to come out of COP 21?

The French government is hopeful that a new universal agreement on climate change will be signed and enforced by all nations by 2020. Unanimously adopting a new emissions target is necessary this time because the emissions limits set up under the Kyoto Protocol will no longer be binding by 2020.

Since October this year, 170 countries have submitted their Intended Nationally Determined Contributions (INDCs) or national climate action plans to the UNFCCC prior to the formal negotiations in Paris.

These INDCs, composed of targets which governments plan to implement in their own countries, should be consistent with the global goal of capping temperature rise at under 2 degrees.

A crucial aspect of this new agreement is a commitment to finance projects in developing and vulnerable countries that will mitigate as well as help them adapt to the impacts of climate change. The UN, under the Green Climate Fund, is hoping to raise US$100 billion per year by 2020 to finance such initiatives. Policy analysts say financing could be one of the sticking points at the Paris talks.

5. How will the talks affect you and me?

Many countries are already implementing measures to reduce emissions but some of the biggest policy reforms required to reduce carbon emissions would be to shift energy production from fossil fuels to renewable sources.

For governments, this would mean scrapping subsidies for these industries. There is also a growing movement among Investors and companies to divest their coal and oil holdings and finance cleaner alternatives such as solar and wind energy instead.

Investing in energy-efficient technologies is also seen as an important means to reduce energy use and put less pressure on resources. In some countries, companies may also soon be required to report their environmental footprint and submit a concrete action plan on how to reduce that.

More funds may also go to conserving forests to absorb carbon, instead of converting them into farmland for agricultural commodities.

Meanwhile, new taxes may be levied on goods and services that pollute the environment, which would mean that consumers may have to pay more for them. On the other hand, clean technologies such as electric vehicles and solar power may become cheaper as more investment is funnelled into these industries.

While some experts say that current national pledges still fall short of what’s needed to make a big dent in emissions, they agree that a weak agreement is better than no agreement at all. It would be a great starting point for countries to start taking unilateral action and implement policies that would contribute to a greener, better world.

At a time when terrorist activities and geopolitical crises are dominating the global agenda, we need something that would restore hope for the future. A successful agreement from Paris would do just that.