For the past four years, Southeast Asia has largely escaped the thick bouts of smoke that enshroud much of the region known as “the haze”. But the likely return of the El Niño dry weather phenomenon is testing the fire preparedness of the regional bloc as northern Asean experiences some of the worst air pollution of the last decade.

To continue reading, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

Smoggy skies in northern Thailand have led to levels of PM2.5 – fine particle air pollution that penetrates deep into the lungs – rocket to 22 times the recommended limit by the World Health Organisation – and hospitalised nearly 2 million people with respiratory illnesses since the start of the year.

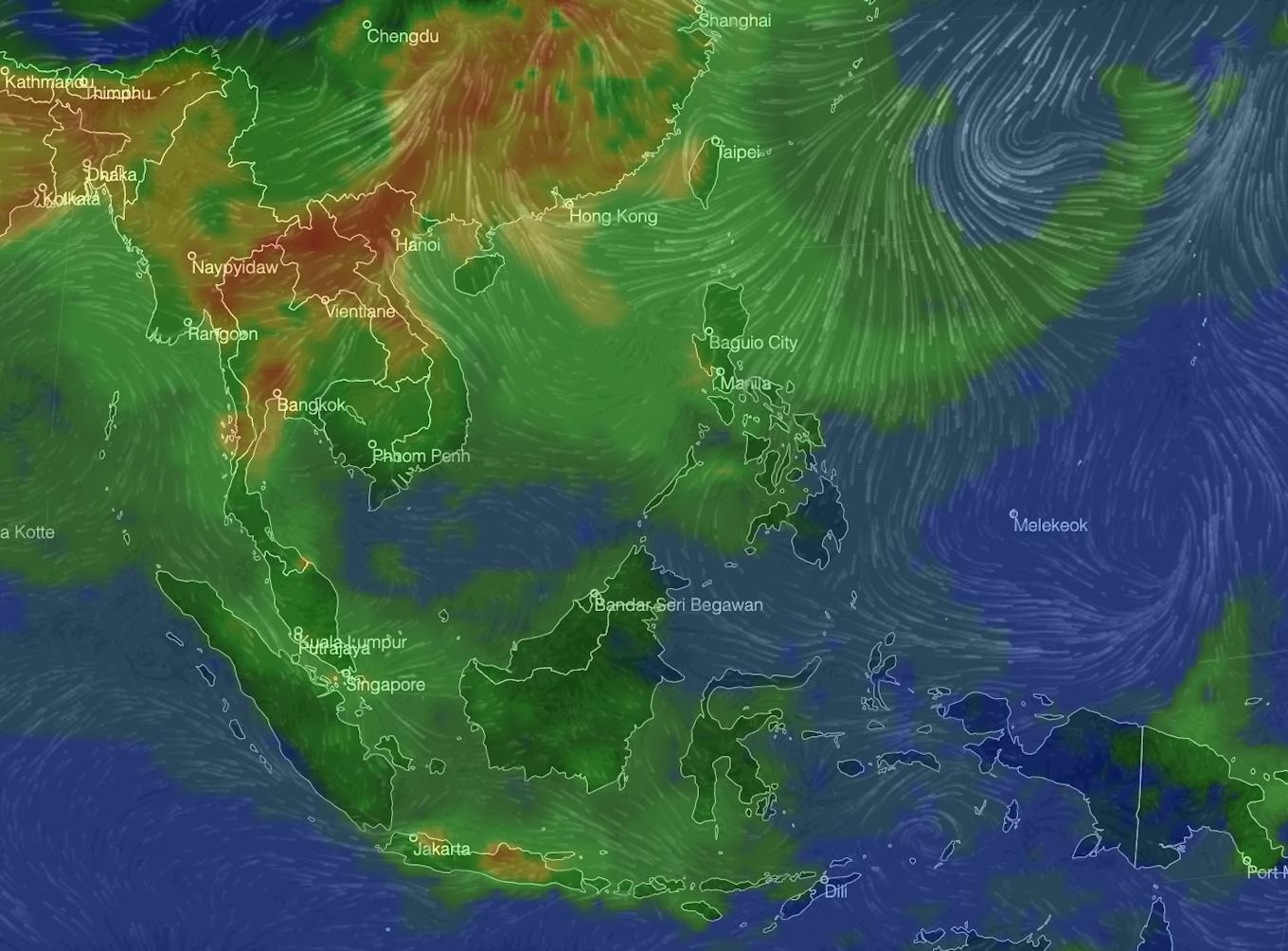

Laos, southern Myanmar, and northern Vietnam have experienced similarly poor air quality. This week, Luang Prabang, Yangon and Hanoi ranked among the cities with the world’s worst air pollution, according to IQAir, a community air pollution monitoring firm.

Seasonal agricultural waste burning has shouldered some of the responsibility for northern Asean’s smog.

“It is too early to blame a particular company or industry [for the haze in northern Asean], but previous episodes have been linked to the expansion of maize contract farming to supply regional and global livestock feed supply chains,” said Faizal Parish, director of Kuala Lumpur-based nonprofit Global Environment Centre (GEC).

“There is also the burning of rice straw and other agriculture residuals [that contributes to the haze],” he told Eco-Business.

The red areas across northern Thailand, southern Myanmar, Laos and northern Vietnam indicate unhealthy air quality. Green areas in Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore and most of Indonesia indicate better air quality. Image: IQAir Earth

Now, scientists worry that the likely return of El Niño could mean smoky skies in the rest of the region as the dry season approaches.

The last few years have seen an unusual run of consecutive La Niña events, meaning wet weather in much of the region. But now the weather pattern could switch to El Niño conditions, said Professor Ben Horton, director of the Earth Observatory of Singapore, a unit of Nanyang Technological University that monitors climate change.

El Niño and La Niña are opposite phases of the El Niño Southern Oscillation (ENSO), a change in temperature between the ocean and the atmosphere over the east-central Tropical Pacific. El Niño is a warm phase, La Niña is a cold phase.

The last El Niño spell, in 2016, exacerbated forest fires in Southeast Asia, mainly on Indonesian peatlands drained for palm oil and pulp and paper production, which killed an estimated 100,000 people prematurely from smoke inhalation and cost US$35 billion to bring under control.

Horton said projections that the region is heading into an El Niño are “not concrete enough yet”.

However, a returning El Niño could result in unprecedented heatwaves, making 2023 hotter than 2022, Horton projected. Such heatwaves could result in food and water insecurity and poverty for millions of people, he noted.

Fire ready?

Faizal Parish, director of Kuala Lumpur-based nonprofit Global Environment Centre (GEC), said that the intensity of the fires and haze this year will depend on the severity of the drought as well as fire prevention measures.

He said there was a risk that some Asean countries have become “complacent” after successive wet years.

However, he said Indonesia should be better prepared than in 2015, after which the government agencies responsible for fire and peatland management were strengthened and efforts were taken to prevent fires from breaking out in vulnerable areas.

Many of the fires were caused deliberately by farmers, as burning the land is a cheaper way of clearing it for planting than using machinery. Peatlands drained to grow crops by industrial plantation companies are vulnerable to fire and will continue to burn long after they catch fire, as the carbon-rich soil burns underground.

“I believe that Indonesia is preparing well for El Niño. However for other Asean member states, I am not sure as budgets and capacity for fire prevention are still very limited in other countries as evidenced by the massive fires and haze in northern Asean,” Parish said.

Parish said his organisation is not expecting a drought and haze as severe as 2015, adding that such phenomena are hard to predict.

GEC is helping the Asean secretariat develop an investment framework for haze-free sustainable land management intended to be completed by September.

In February, Indonesian officials said there was a 50 per cent chance of an El Niño event this year and warned farmers and plantation firms to be on guard. Plantation firms have reportedly spent millions on fire prevention and suppression since the 2015 haze outbreak.

Indonesia has suffered particularly severe haze outbreaks that have affected the rest of the region, including neighbouring Malaysia and Singapore, in 1997, 2015 and 2019.