The Covid-19 pandemic has led to a temporary fall in air pollution in many parts of the world, as economic activity has ebbed and movement restrictions have de-clogged congested cities. But smog was still a big killer in 2020, according to analysis from environmental group Greenpeace and Swiss air quality technology firm IQAir.

To continue reading, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

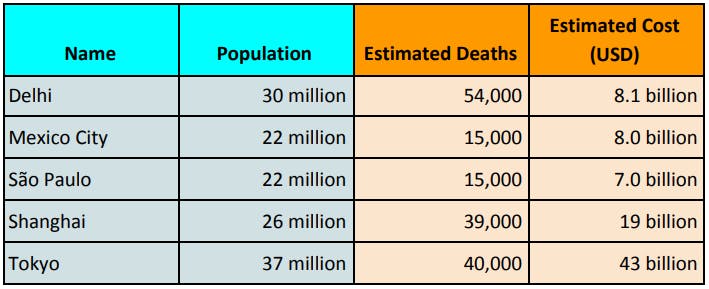

In the world’s five biggest cities, Shanghai, Tokyo, Dehli, Mexico City, and São Paulo, small particulate matter in the air known as PM2.5, which penetrates deep into the lungs, killed 160,000 people prematurely in 2020.

Particulate pollution causes health problems such as lung cancer, heart disease, stroke, and even diabetes.

Delhi, the world’s most polluted city, sustained an estimated 54,000 avoidable deaths due to PM2.5 air pollution in 2020 — more than five times the reported deaths from Covid-19 to date.

Jakarta, which overtook Beijing in a ranking of the world’s smoggiest urban centres last year, lost 13,000 lives to air pollution in 2020, more than double the Covid casualty rate in the Indonesian capital.

Tokyo, which for an Asian city has relatively clean air — with PM2.5 levels about 70 per cent above the limit deemed safe to breathe by the World Health Organisation — registered 40,000 deaths from bad air in 2020, while losing 1,180 people to the coronavirus.

Greenpeace’s study also recorded the economic cost of air pollution in a year in which the global economy went into recession.

No city in the study suffered as big an economic contraction as Tokyo, which lost US$43 billion to smog in 2020. Shanghai lost US$19 billion to air pollution.

The cost of air pollution is calculated based on healthcare costs and lost productivity.

Los Angeles recorded the highest financial cost of PM2.5 air pollution per capita, at US$2,700 per resident, while Jakarta lost the equivalent of 8.2 per cent of the city’s total GDP to poor air quality.

“The fact that poor air quality claimed an estimated 160,000 lives in the five largest cities alone should give us pause, especially in a year when many cities were seeing lower air pollution levels due to less economic activity,” said Frank Hammes, chief executive of IQAir.

Aidan Farrow, air quality scientist at Greenpeace Research Laboratories, the environmental group’s science unit in the United Kingdom, told Eco-Business that the research demonstrates the need to urgently scale up clean energy, build electrified, accessible transport systems and end reliance on polluting fossil fuels.

“The chance that improving air quality could reduce our susceptibility to diseases like Covid is a strong argument in favour of action that will improve air quality and another reason to shift from fossil fuel to clean renewable technology,” he said.

Some studies have shown that air pollution makes it easier for people to contract the coronavirus, as well as develop more severe symptoms. One paper suggested that 15 per cent of Covid deaths worldwide, and up to 27 per cent of Covid deaths in East Asia, could be attributed to long-term exposure to air pollution.