Protected areas are places that conserve nature and cultural resources. Although they are often largely free of human interference, many areas permit a certain amount of activity, such as growing crops.

The new study, published in Nature Sustainability, finds that cropland has expanded at an “alarming” rate in protected areas between 2000 and 2019.

The study uses three datasets, covering different time periods, to assess the extent of this expansion. It shows that the annual rate of cropland expansion grew by as much as 58-fold over nearly two decades.

This poses a “great potential threat to biodiversity conservation” and, without changes in crucial protected areas, the global land conservation target for 2030 “will not be reached”, the study says.

A researcher who was not involved in the study says that the findings highlight “the need for a real conversation about what we expect protection to look like” in achieving nature targets this decade.

Global protected areas

There are more than 260,000 protected areas around the world, including national parks, forests and wildlife sanctuaries. Such areas have different protection requirements, ranging from strict nature reserves to larger zones that allow a certain amount of sustainable use of natural resources.

They are an “important tool” for storing carbon, safeguarding biodiversity and reducing risks from climate hazards, according to the International Union for Conservation of Nature.

“

People are going to encroach on protected areas if there aren’t alternative livelihoods available and I don’t think there’s meaningful consideration or investment in what that can look like.

Dr Caitlin Blaser-Mapitsa, senior lecturer, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg

Almost every country in the world agreed to conserve 30 per cent of the world’s land and 30 per cent of the ocean by 2030 as part of a wider nature deal at the COP15 biodiversity summit in Montreal last year.

This would be a significant increase. According to a March 2023 Protected Planet report, just over 17 per cent of the world’s land and inland waters are currently protected and conserved areas. That figure is almost 28 per cent in the UK and 13 per cent in the US.

Previous research has estimated that 6 per cent of global protected area is used for croplands. To understand how this area is changing over time, the new study uses satellite imagery to remotely assess the extent of cropland expansion in protected areas around the world.

The researchers mainly focus on one high-resolution global cropland dataset derived from previous research, which covers expansion from 2000 to 2019. This is a comprehensive dataset frequently used for cropland studies, several researchers tell Carbon Brief.

The study also assesses two other datasets on global land cover changes from studies using similar high-resolution maps and covering slightly different time periods.

All three datasets show an increase in croplands in protected areas, but with varying results, ranging from an increase of 7,559 square kilometres (km2) over 2000-15 to 53,383km2 over 2000-20.

As of April 2023, the total protected land area around the world is 21,513,805 km2.

Despite the large ranges, Prof Erle Ellis from the University of Maryland, Baltimore County, who is one of the co-authors of the research, says that the study shows that remote sensing using satellites is a “very effective” tool to assess changes in global protected areas. He tells Carbon Brief:

“It really is, I would say, one of the first truly data-driven global assessments of cropland in protected areas.”

Prof Luca Börger, a professor in ecology and biodiversity at Swansea University, who was not involved in the study, tells Carbon Brief that the findings are “timely and relevant” and in line with other research. He says:

“The expansion of agriculture or croplands used in protected areas is quite worrying and one needs to understand why.

“Even by using different datasets with contrasting definitions and accuracy of cropland definitions, consistently [the researchers] show that the rate of cropland expansion in protected areas has increased considerably.”

Cropland ‘encroachment’

The study also looks at how the extent of cropland growth in protected areas differs around the world. It finds that 79 per cent of this expansion over 2000-19 took place within the Afrotropics, a region largely encompassing sub-Saharan Africa.

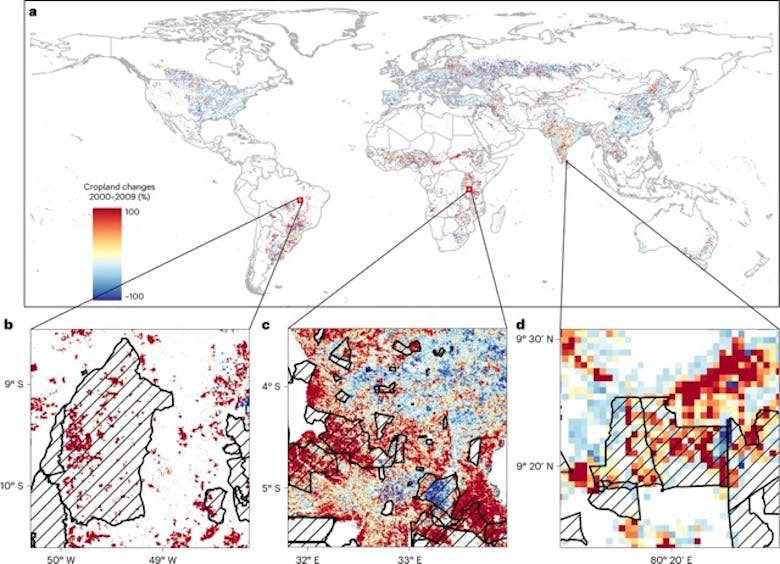

The map below shows the percentage change of cropland in protected areas around the world from 2000-19, based on the main dataset used in the study. The red areas indicate an increase in cropland changes, while the blue areas show a decrease.

Global distribution of cropland changes in protected areas (a). Areas in red are places where cropland changes have increased, while areas in blue show a decrease. The bottom panels show three examples of areas with significant cropland changes: a large protected area (b); the Afrotropics (c); and a category of protected area with strict protection (d). The hatched areas in (b-d) mark the boundaries of existing protected areas. Source: Meng et al. (2023).

The study says that funding shortages, poor governance, poverty and illegal wildlife trade hinder conservation management in the Afrotropics.

Börger notes that this region has “less cropland area” to begin with. Furthermore, he says it contains “populations that are often marginalised”, who “actually need access to more food” – which may explain part of the increase in recent decades.

Dr Caitlin Blaser-Mapitsa, a senior lecturer in monitoring and evaluation at the University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, notes that croplands or other human activity in protected areas should not always be viewed as an “encroachment”. She tells Carbon Brief:

“For Africa to reach this 30 per cent goal, it fundamentally implies including settled areas more robustly within protected areas. I think there’s often a kind of assumption that settlement within protected areas is bad, like it makes it less pristine. I really don’t think that’s the model of conservation that’s appropriate in the region.

“If we are going to protect 30 per cent of the land soon, that has to be with people – both inside and outside of the protected area.”

Reasons for expansion

One potential reason for cropland expansion is poor management of protected areas, the study says. Blaser-Mapitsa says that while she does have “real concerns of the quality of the management”, there are other factors that need to be considered. She adds:

“I think a lot of it really is about the model of resourcing. People are going to encroach on protected areas if there aren’t alternative livelihoods available and I don’t think there’s meaningful consideration or investment in what that can look like.”

The study notes that a holistic approach to conserving areas is needed, as stricter rules to halt cropland expansion in protected areas can result in “severe threats to global justice and harm people who are already marginalised”.

Ellis says it is clear that “just having cropland in a protected area doesn’t necessarily mean there’s a problem. It depends on the kind of protected area.” But, he adds:

“You wouldn’t want to see really rapid expansion…and that is what’s being measured here. You want to see a more stable cropland pattern in those settings.”

In 2019, protected areas under strict management regulations showed less pressure from cropland expansion than areas with more flexible rules, the study says. However, it notes “drastic changes” in cropland expansion since 2000 in one type of strictly protected area covering wilderness areas with little human activity.

Börger says crop growth increases in even well-protected wilderness areas is “higher than I would have expected” and “quite worrying, because these are the last wilderness areas we have globally”.

The study notes that expanding croplands can disrupt the connectivity of landscapes, cause terrestrial biodiversity loss and reduce the effectiveness of protected areas.

The researchers also combine information around cropland dynamics and species extinction risks in protected areas to assess whether areas with faster rates of cropland expansion also experience faster extinctions.

This examination focuses on birds, mammals, amphibians and reptiles that were “imperilled by agricultural activities”.

Although the study finds consistently high values for cropland expansion and species risk in the Afrotropics, national parks and large protected areas, cropland expansion overall did not have a significant impact on biodiversity extinction risk in protected areas.

Power of small protected areas

Previous research has looked at global cropland expansion in large protected areas since 1990, but the new study also focuses on smaller areas of at least 0.09 hectares, or 900 m2.

The study finds that smaller protected areas provide more effective protection than relatively large areas. Areas smaller than 20km2, although comprising an overall small portion of global protected areas, have experienced less cropland expansion than larger areas.

Ellis says that this may be because most smaller protected areas tend to be in wealthier parts of the world, adding:

“It actually takes a lot of effort per unit area to make a small one. The big ones tend to be these projects that are more international projects.”

He continues:

“In Africa, you’re not going to see a million small protected areas…You may have small conservation areas that are not listed or strongly protected. Being present in this database [of protected areas] and being small tends to be associated with countries that are wealthier and have more resources to manage these things.”

Blaser-Mapitsa says the study raises issues that need to be further examined in the years ahead. She tells Carbon Brief:

“I think what this study points to is the need for a real conversation about what we expect protection to look like in this 30 per cent that we’re looking for.

“I think very often these targets sound good because they’re quite reductionist and sometimes they mask the complexity, which is where the real conversations need to happen.”

This story was published with permission from Carbon Brief.