REDD+ projects make up the largest number of carbon credits in the voluntary carbon market (VCM), which was worth nearly US$2 billion in 2021 – almost fourfold its 2020 value.

To continue reading, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

This is a long way since the first REDD credit was issued under the Voluntary Carbon Standard in 2011.

In the span of a decade, REDD+ – which stands for Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and forest Degradation, with the “+” referring to sustainable forest management, conservation, and reforestation – has gone from a little-known United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) framework to a critical policy solution for rainforest nations.

Up until last year, projections of the growth of the VCM had been bullish. The non-profit initiative Ecosystem Marketplace painted an optimistic picture for 2022 in its annual “State of the Voluntary Carbon Markets” report, as carbon prices trended upwards.

In 2021, carbon prices soared to a global average of US$4 per tonne – a value not seen since 2013 – driven largely by rising prices for nature-based credits, which often trade at a premium due to the additional non-carbon benefits they bring, such as local community development and biodiversity conservation.

However, since its peak at the start of 2022, the price of nature-based offsets has slumped by over 90 per cent, to US$1.82 at the time of publication, coinciding with macroeconomic headwinds and media reports that have called into question the environmental claims surrounding certified rainforest credits, which are used by notable international corporations.

Nature-based Global Emissions Offsets (N-GEO), or carbon credits generated by projects that reduce, remove, or prevent carbon emissions through nature-based solutions, were trading at a premium over other offsets in the voluntary carbon market in 2022. However, their prices have since plummeted. Source: CarbonCredits.com

Criticisms of REDD+ are not new. As a type of avoidance carbon credits, which focus on preventing greenhouse gas emissions that would have otherwise been released into the atmosphere, most observers have pointed to how REDD+ offsets can never perfectly predict long-term emission reductions.

Charles Bedford, chief impact officer of the global carbon markets investing firm Carbon Growth Partners, shares this sentiment. He said: “It’s easy to pick fights in the carbon market because all carbon projects are based upon a prediction about the future, and all predictions about the future are wrong. It’s just about how much.”

Before becoming a carbon markets investor, Bedford was the Asia Pacific managing director of The Nature Conservancy, a global non-profit conservation group. He left The Nature Conservancy to start Carbon Growth Partners in 2021, with the aim of unlocking more funding for nature conservation and restoration projects – traditionally the realm of philanthropic causes – while generating financial returns for investors.

Having worked on conservation solutions, including market-based solutions, for over two decades, Bedford has seen the carbon offsets market develop since its infancy. He believes that REDD+ projects remain the best bet for incentivising developing countries with significant forest cover – which tend to be nations with low governance, as Bedford points out – to prevent deforestation.

“Not cutting down a forest means forgoing income from harvesting timber. So if we don’t figure out a way to replace the income that poor countries can get from harvesting the forest, then they will harvest the forest,” Bedford said.

Under the REDD+ framework, developing countries can receive results-based payment for reducing emissions from deforestation. But there have been controversies around how the financial incentives and benefit-sharing mechanisms are structured in these projects, and how consent is obtained from Indigenous peoples and local communities that own the land.

For these reasons, it takes “a lot of effort” to get comfortable with such projects. “We believe in REDD+, but it takes a fair bit of due diligence to be comfortable with REDD+ projects, so we’ve only invested in a few of them,” Bedford shared with Eco-Business on a trip to Cambodia’s Keo Seima and Southern Cardamom REDD+ projects that several media outlets were invited to.

Charles Bedford (middle) looking at a pile of over 6,000 confiscated chainsaws amassed from the last decade at the Sre Ambel Patrol Station within the Southern Cardamom REDD+ project. Image: Eco-Business/Gabrielle See

Bedford said his firm has done “shallow” due diligence on all 30 REDD+ projects that have issued considerable credits, and “deep” due diligence on the top ten projects, which account for about 90 per cent of these issued credits. To date, Carbon Growth Partners has only invested in REDD+ projects in Asia and Latin America, like Cambodia’s Keo Seima and Colombia’s Selva de Matavén, but is starting to look at Africa after a recent hire there.

Amid the market turbulence last year, the firm’s original fund, Carbon Growth Opportunities Fund, outperformed other benchmarks like the global derivatives marketplace CME Group’s Nature-based Global Emissions Offsets (N-GEO) and GEO. The investment manager has attributed this performance to its focus on high-quality carbon assets and diversified portfolio.

In terms of project type, the fund was less exposed to REDD+ and non-CORSIA (Carbon Offsetting and Reduction Scheme for International Aviation) renewables, and more exposed to blue carbon and cookstoves, which held up better in value compared to the first two project types last year.

As the VCM seeks to restore trust, “integrity” and “quality” have become the latest buzzwords among industry players. For this reason, numerous guides for companies looking to buy credible forest carbon offsets have also been freshly penned this year by the World Business Council for Sustainable Development (WBCSD) and eight conservation and Indigenous organisations.

Bedford ran Eco-Business through a checklist his firm uses to “go deeper” into the quality of REDD+ projects, once basic due diligence, such as verifying credentials of the project on a trusted registry and assessing counterparty risks, has been done.

The three factors he looks out for in REDD+ offsets:

1. A conservative baseline

There are two main components in a conservative baseline, Bedford said. First, the deforestation rate in the country must not be overestimated at the time of assessment. Second, the deforestation rate for the country where the project is located must not go below what was estimated. For instance, if the deforestation rate for a country was conservatively estimated at 1 per cent but turned out to be 2 per cent after a decade, the project is theoretically generating credits twice as good as it claimed.

The world’s biggest carbon credits certifier Verra recently updated its new consolidated methodology, which uses a jurisdictional allocation approach to determine project baselines so that projects no longer have to rely on a reference region – or a nearby area with similar drivers of deforestation – to project future deforestation. Project baselines are also now re-assessed every six years instead of ten.

Project design documents (PDDs) typically have 60 to 70 pages dedicated to complex calculations of the baseline emissions and carbon stocks within the project, which is particularly important in the avoided deforestation world.

“It’s not just a REDD+ problem,” said Bedford, who added that a conservative baseline is also important in other project types like cookstoves and renewable energy, “But it’s a REDD+ problem because it’s just a little harder to make predictions about the future and be right about them.”

Carbon Growth Partners outsources the work of poring over PDDs and cross-checking the historical data cited in them to third party vendors with skill sets in remote sensing and GIS (Geographic Information Systems) analysis in forestry.

Rating agencies, like Sylvera, offer subscription access to baseline estimations, which Carbon Growth Partners also uses. “That gives us an easy first step and if we feel like we need to get deeper, then we’ll hire somebody to go even deeper,” said Bedford. “Often, the big buyers in the corporate sector will use rating agencies as a surrogate to do the hard due diligence for them.”

A staff from the Jahoo Gibbon Camp, a sustainable ecotourism camp within the Keo Seima REDD+ project, conducting a maintenance check on an arboreal camera trap, which contributes to the biodiversity monitoring at the site. Image: Eco-Business/Gabrielle See

Bedford emphasised that his firm is “not dependent” on rating agencies. They are either employed as upfront screening tools to weed out poorly rated REDD+ projects, or from a defensive perspective, to keep up to date with rating changes for projects it owns, in case the changes affect the market value of these projects.

2. Strong implementation capacity

Potential buyers should look at the track record and experience of project developers, who are non-governmental organisations (NGOs) or private companies, to assess how well they can implement projects with rural communities in low governance countries.

While most of this due diligence can be done online, Bedford said that he prefers to meet project developers and partners where the project is located, so they can walk him through it. For this reason, Bedford visited Cambodia’s Keo Seima REDD+ project, which is supported by the international conservation NGO Wildlife Conservation Society, before investing in it. He is also considering investing in the Southern Cardamom REDD+ project which he visited.

As of 19 June, Verra has opened up a review of the Southern Cardamom project on the back of allegations of rights abuses by the NGO Human Rights Watch. The project is suspended from any new credit issuances while the investigation is ongoing.

3. Ownership of the project by Indigenous peoples and local communities

For more qualitative aspects of the project, like its ownership by Indigenous peoples and local communities, Bedford said the company would send independent people on the ground to assess them. These people will need to be knowledgeable about the country, the local contexts, and what a good development project looks like.

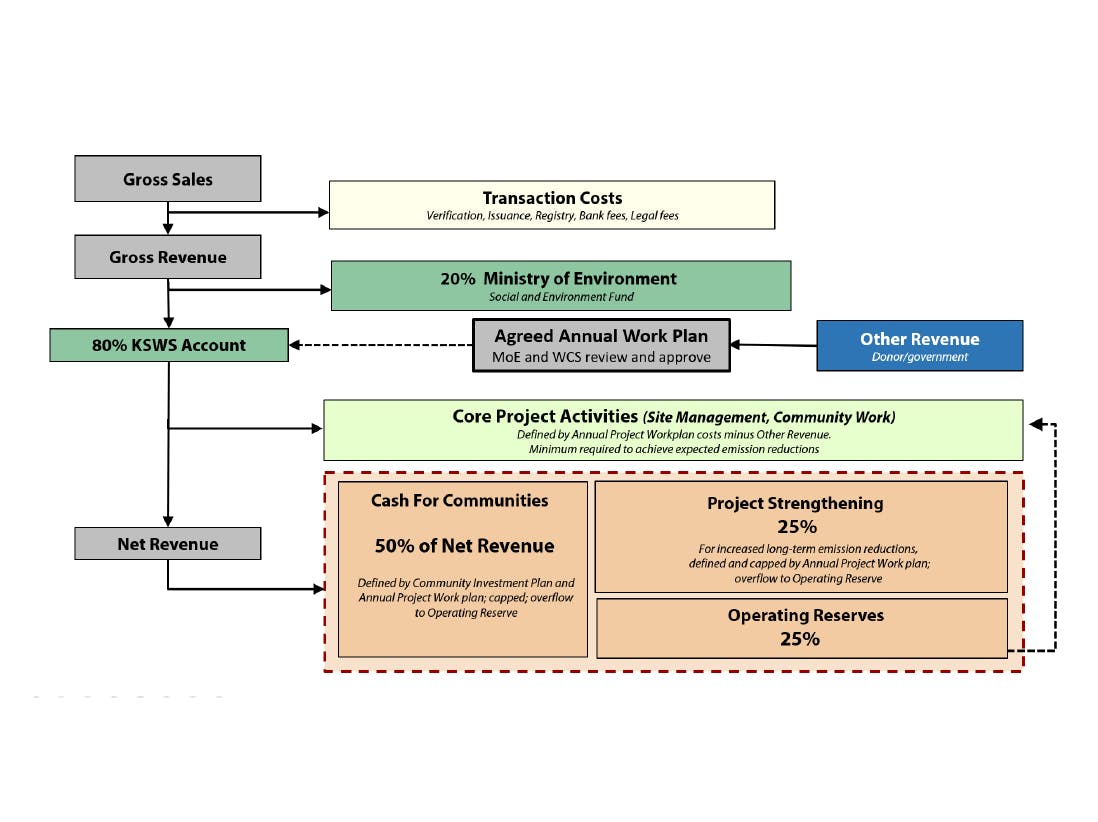

The issue of ownership concerns both figurative buy-in from the communities – determined by speaking to people on site – as well as literal ownership, around deal structure and funds flow. “The traceability of funds from the retiree [of the carbon credit] back down to where and how much is spent on the ground is important both from a project success and equity perspective,” said Bedford.

A flowchart showing how the Keo Seima REDD+ revenue feeds back into government, project, and community funding. Source: WCS Cambodia

Additional factors:

1. Country risk

A country can have high sovereign risk, which is the risk of a government defaulting on its debt, but potentially still carry less risk of reversal in emissions avoidance. Bedford cited the example of Cambodia, which has relatively high economic and political risks, but generally “scores well” in his view for REDD+ projects due to its commitment to the REDD+ model, as well as the clarity around its nationally determined contribution (NDC) and the financing needed to achieve it.

2. Implementation risk

This refers to how well partners can execute the project on the ground, which depends on their experience, political connections, and sensitivity to local communities.

3. Reputational risk

This concerns the benefit sharing agreement of projects and the values of the partners, which Bedford prefers to assess by visiting them in person on the ground. Such site visits helps him to get to know who they are and how they think about the project, as well as their reputation on the ground, said Bedford.

Media access to the sponsored trip to Cambodia’s Southern Cardamom and Keo Seima REDD+ projects was facilitated by Everland.

Read more about the complex dynamics behind REDD+ projects in Cambodia in this special report.