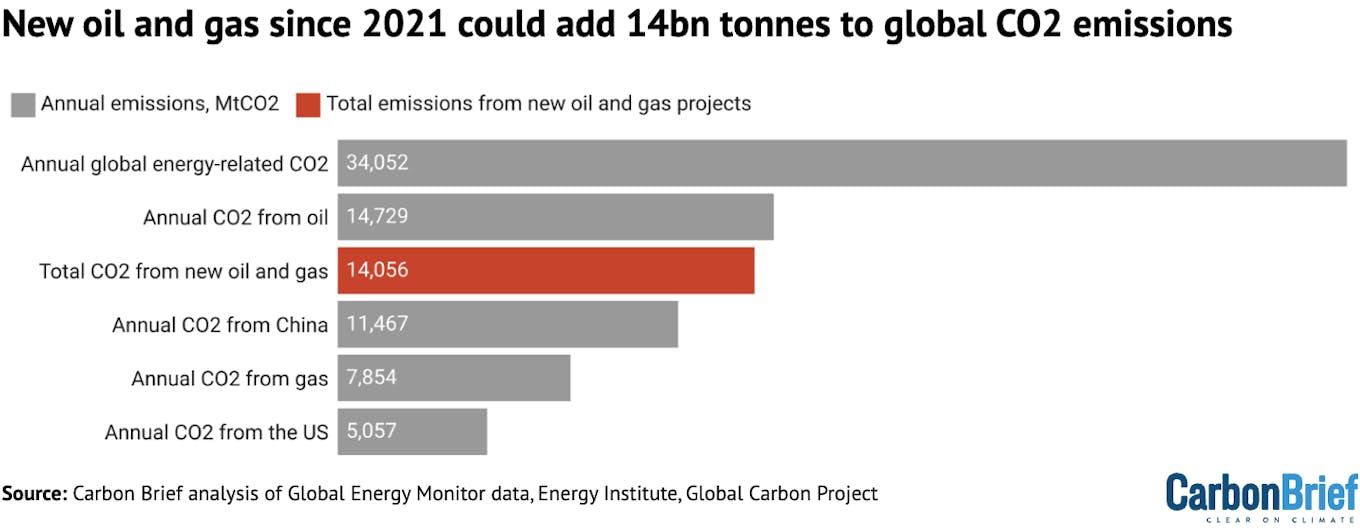

This would be equivalent to more than an entire year’s worth of China’s emissions.

It includes 8GtCO2 from new oil and gas reserves discovered in 2022-23 and another 6GtCO2 from projects that were approved for development over the same period.

These have all gone ahead since the International Energy Agency (IEA) concluded, in 2021, that “no new oil and gas fields” would be required if the world were to limit global warming to 1.5°C .

Since then, world leaders gathering at the COP28 summit at the end of 2023 have also agreed to “transition away from fossil fuels”.

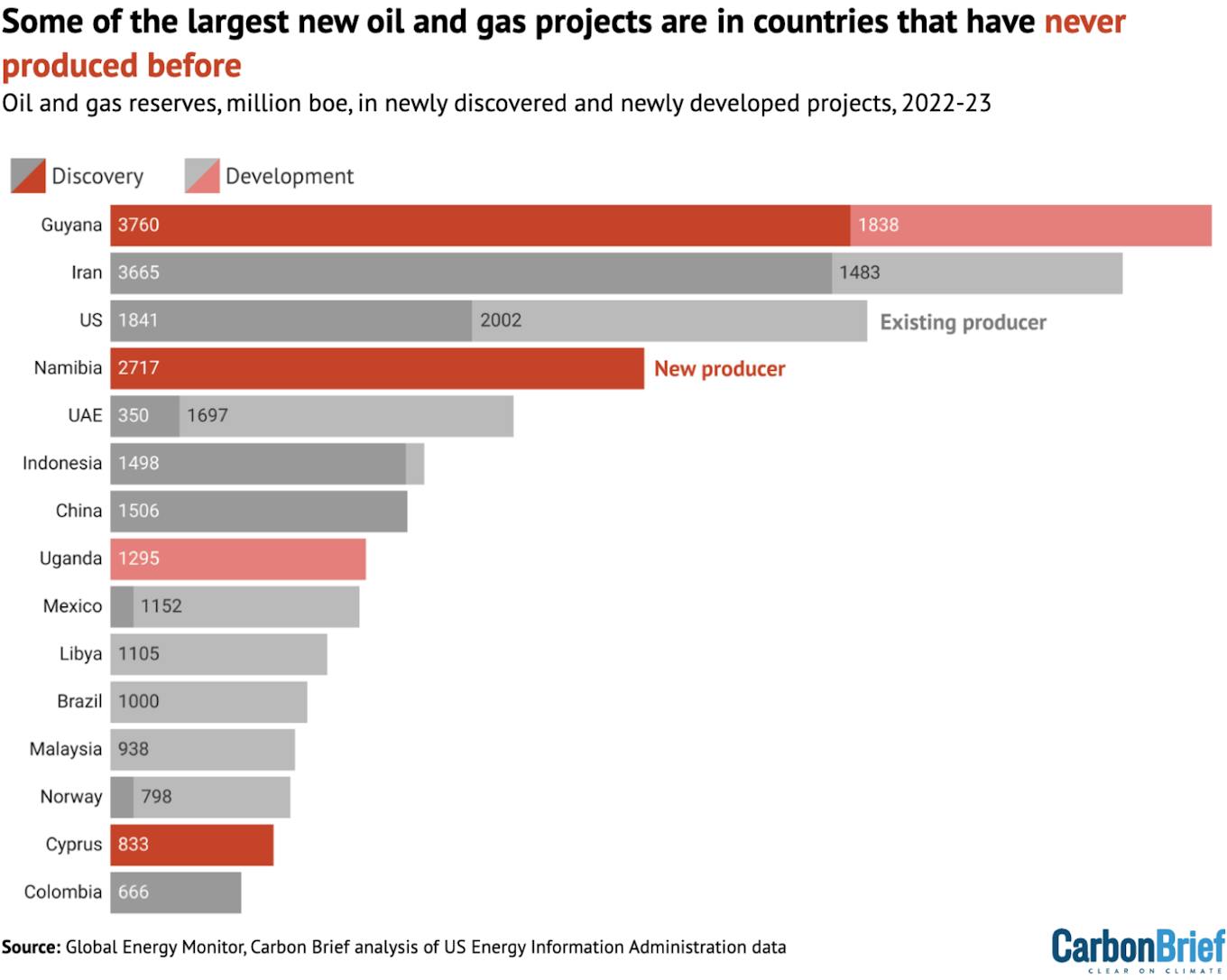

Despite this, nations such as Guyana and Namibia are emerging as entirely new hotspots for oil and gas development. At the same time, major historic fossil-fuel producers, such as the US and Iran, are still going ahead with large new projects.

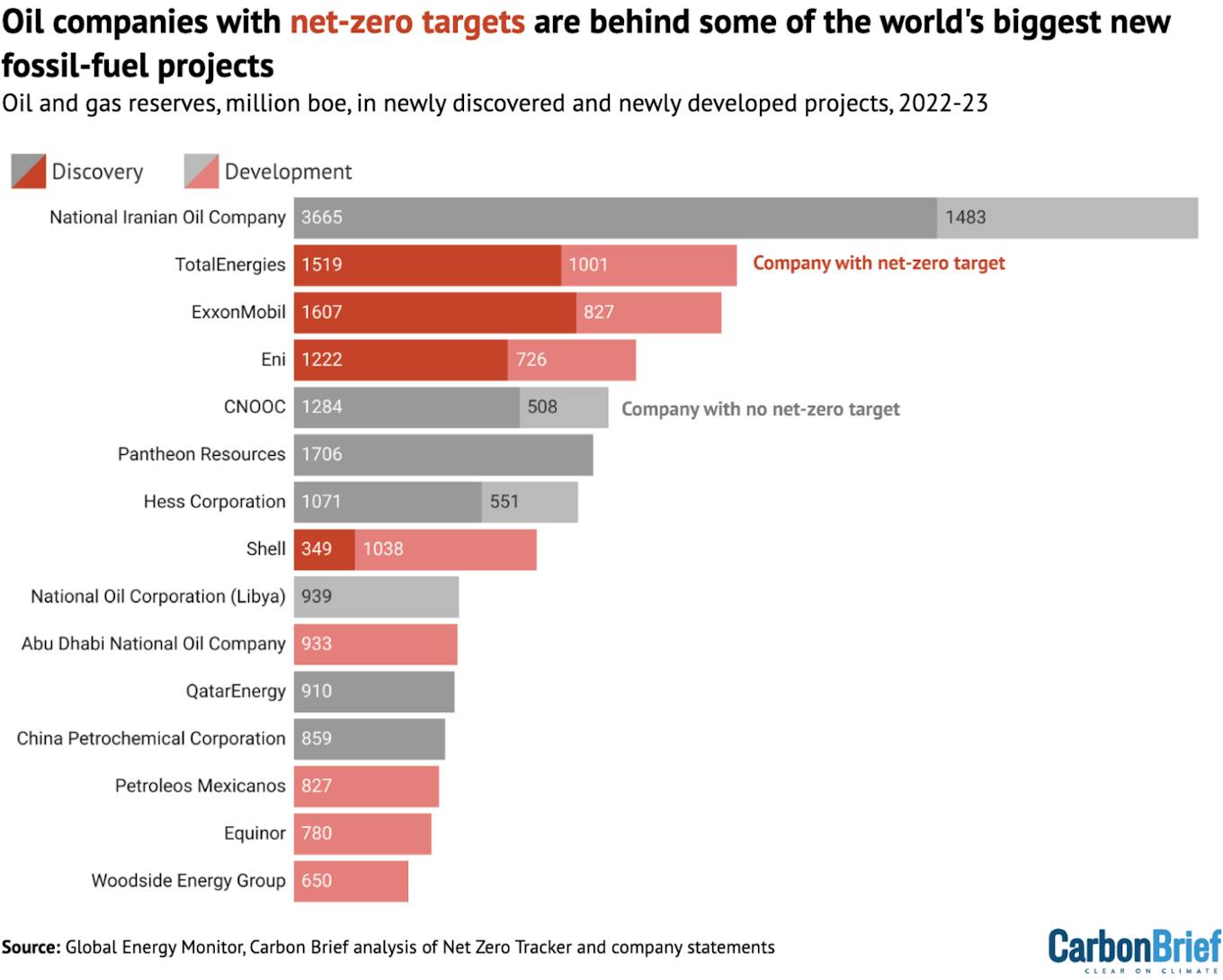

Additionally, oil majors such as TotalEnergies and Shell that have made public commitments to climate action, are among the biggest players investing in new oil and gas extraction around the world.

More oil, more CO2

In 2021, the IEA issued its first “net-zero roadmap”, setting out a pathway for the world to limit warming to 1.5°C. The influential agency concluded that:

“Beyond projects already committed as of 2021, there are no new oil-and-gas fields approved for development in our pathway.”

This statement has become a rallying cry for campaigners and leaders pushing for a phase out of fossil fuels.

The IEA has since clarified that there would be no need for new oil and gas developments if the world gets on track for 1.5°C. It has also slightly softened its language, by allowing for new oil and gas projects with a “short-lead time” within its 1.5°C scenario.

Yet it has also warned of the risk of “overinvestment” in new developments, noting that current spending is “almost double” what would be needed under its 1.5°C pathway.

In any case, the IEA’s message has been widely ignored by oil and gas companies, which have continued to search for new extraction opportunities.

In its new global oil and gas extraction tracker, GEM identifies 50 new sites discovered in 2022 and 2023, after the IEA issued its initial net-zero roadmap. The oil and gas reserves from these projects amount to 20.3m barrels of oil equivalent (Mboe).

The tracker also identified a further 45 projects that have reached “final investment decision” (FID) since the IEA’s roadmap, with an extra 16Mboe of reserves. FID is the point at which companies decide to move ahead with a project’s construction and development.

If all the oil and gas in the newly discovered reserves is burned in the coming years, an extra 8GtCO2 would be released into the atmosphere, according to Carbon Brief analysis. Adding the reserves discovered between 2022-23 brings this total to 14.1GtCO2.

This is equivalent to more than one-third of the CO2 emissions from global energy use in 2022, or all the emissions from burning oil that year, as shown in the chart below.

Total CO2 emissions that would be emitted if all the oil and gas reserves from newly discovered and newly developed projects between 2022-23 were burned (red) compared to annual emissions from different countries and energy sources in 2021 (grey). CO2 emissions were calculated based on oil and gas reserves listed in the GEM global oil and gas extraction tracker database. When the fuel type was not specified, Carbon Brief assumed a 50:50 split. Source: Carbon Brief analysis of Global Energy Monitor data, Energy Institute, Global Carbon Project.

These findings are in line with mounting evidence that both company and government plans for fossil fuels are not aligned with their own climate goals.

According to the most recent UN Environment Programme “production gap” report, companies are planning for gas and oil production that is 82 per cent and 29 per cent higher, respectively, than would be needed in a 1.5°C pathway.

The remaining “carbon budget” of emissions that can be released while retaining a 50 per cent chance of limiting warming to 1.5°C is just 275GtCO2, according to the Global Carbon Budget consortium of scientists. Burning all of the contents of the new oil and gas schemes identified by GEM would use up 5 per cent of this remaining budget.

Moreover, the GEM report points out that new projects take, on average, 11 years to start producing significant amounts of oil and gas. This means that most will not enter production until the 2030s.

By this point, according to the IEA, fossil-fuel demand would have fallen by “more than 25 per cent” if the world gets on to a 1.5°C-compliant pathway.

GEM also notes that its analysis likely underestimates the scale of new fossil fuel developments. It excludes smaller sites and those where the size has not been publicly announced, such as new gas fields discovered in Saudi Arabia in 2022.

The IEA updated its net-zero scenario in 2023 to reflect the continued expansion of fossil-fuel projects since its previous report. It stated that:

“No new long lead time conventional oil and gas projects need to be approved for development.”

It added that falling demand for fossil fuels “may also mean that a number of high cost projects come to an end before they reach the end of their technical lifetimes”, again if the world gets onto a 1.5°C pathway.

To reflect the IEA’s new language around avoiding “long lead time” and “conventional” projects, GEM excludes expansions of existing projects and “unconventional” sites from its analysis. The report notes that including them would roughly quadruple the size of the reserves that reached a FID in 2022-23.

Oil majors

Many oil companies have made it clear that they do not intend to wind down their fossil-fuel operations in the near future.

This is true even for those that have made commitments to climate action, such as Shell and TotalEnergies. (Some oil majors have also watered down their pledges in recent months.)

As the chart below shows, many of the companies with the largest share of new oil and gas schemes have also announced net-zero targets.

Top 15 companies by ownership of new oil and gas projects that were either discovered (dark red) or reached their “final investment decision” (light) in 2022-23. Companies often share ownership of projects, so reserves have been divided up based on the percentage share of each project belonging to companies. Source: Global Energy Monitor, Carbon Brief analysis of Net Zero Tracker and company statements.

The top rankings are dominated by publicly traded oil majors, such as ExxonMobil, and national companies, such as the Abu Dhabi National Oil Company (ADNOC) – which is led by COP28 president Sultan Al Jaber. Saudi Aramco, the world’s largest oil company, is missing from the GEM tracker, likely due to the lack of data from Saudi Arabia.

The emissions that could result from new gas fields run by the state-owned National Iranian Oil Company alone amount to 1,700MtCO2, according to Carbon Brief analysis. This is higher than the annual carbon footprint of Brazil.

Meanwhile, oil and gas in new projects being developed by TotalEnergies and ExxonMobil could generate roughly 1,000MtCO2 – equivalent to Japan’s annual total – for each company.

At the recent CERAWeek industry conference, many oil and gas industry leaders argued against a transition to cleaner forms of energy. For example, Saudi Aramco chief executive Amin Nasser told attendees: “We should abandon the fantasy of phasing out oil and gas.”

As companies continue searching for more oil and gas, executives have consistently emphasised that demand for fossil fuels, rather than production, is the problem.

Most recently, in an interview with Fortune, ExxonMobil chief executive Darren Woods placed the blame on the public, who he said “aren’t willing to spend the money” on low-carbon alternatives.

New country ‘hotspots’

New nations, mainly in the global south, are opening up as “global hotspots” for oil and gas projects, according to GEM.

Notably, Guyana is set to have the highest oil production growth through to 2035. Over the past two years, it has already been the site of more new oil and gas discoveries than any other country. Namibia has also opened up as a major new frontier in fossil-fuel extraction.

The chart below shows how nations that have recently been targeted for oil and gas exploration, now make up a large portion of new discoveries and developments.

Top 15 countries by location of new oil and gas reserves that were either discovered (dark red) or reached their “final investment decision” (light) in 2022-23. Source: Global Energy Monitor, Carbon Brief analysis of US Energy Information Administration data.

The expansion of oil and gas production in the global south is a highly politicised topic.

Many African leaders, in particular, argue that their countries are entitled to exploit their natural resources in order to bring benefits to their people, as global-north countries have done. At COP28, African Group chair Collins Nzovu stated that oil and gas were “crucial for Africa’s development”.

(It is worth noting that, according to GEM’s analysis, companies based in the global north such as ExxonMobil, Hess Corporation and TotalEnergies own most of the reserves in the new global-south projects.)

Meanwhile, wealthy oil producers such as the US, Norway and the UAE justify their continued fossil-fuel extraction by saying their production emissions are relatively low. Others, such as the UK, argue that they need to exploit domestic reserves to preserve their energy security.

Even in a 1.5°C scenario, the IEA still includes a significantly reduced amount of oil and gas use in 2050. Most of it goes towards making petrochemicals and producing hydrogen fuel.

However, in last year’s report on the position of the oil and gas industry in the net-zero transition, the agency also emphasises that this does not mean everyone can continue producing.

“Many producers say they will be the ones to keep producing throughout transitions and beyond. They cannot all be right,” it concludes.

This story was published with permission from Carbon Brief.