In the four years since 2015, when some of the worst forest fires on record destroyed 2.6 million hectares of land in Indonesia, the region’s big agribusiness firms have spent millions of dollars on fire prevention and suppression schemes—and a fair amount on public relations to publicise their efforts.

To continue reading, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

But as haze pollution billows from burning forests in Sumatra and Kalimantan to neighbouring Malaysia and Singapore, triggering memories of 2015, a question mark hangs over the effectiveness of Big Agri’s fire-fighting programmes.

Since June, 300,000 ha of land—more than four times the area of Singapore—has burned in Indonesia, much of it carbon-rich peatland drained for agriculture that is particularly flammable in the dry season. A drought projected to stretch into the middle of October has raised fears that this haze outbreak could match 2015, when daily carbon emissions from the fires exceeded those of the European Union.

Schemes such as the Fire Free Village Programme (FFVP), which was started by Singapore-headquartered pulp and paper giant Asia Pacific Resources International Limited (April) in 2015 and later grew into a collective of palm oil firms and green groups called the Fire Free Alliance, were designed to bring an end to the practice of using fire to clear land—the main cause of the haze.

“

This is a cultural and behavioural change challenge equivalent to getting people to wear seatbelts in cars or give up smoking.

Anita Neville, senior vice-president, group corporate communications, Golden Agri-Resources

The alliance’s aim is to educate local communities of the dangers of using fire, and kill a slash-and-burn culture that has persisted for more than four decades. Financial incentives in the form of infrastructure grants are awarded villages that stay fire free, and tools and training provided to farmers to clear land without burning it.

Are these programmes working?

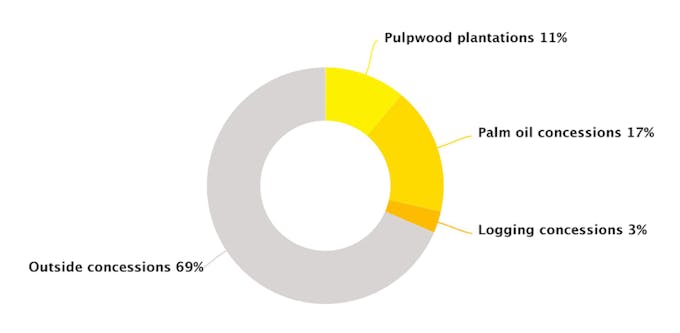

Fire alerts by land use area, August - September 2019. Source: Global Forest Watch

The big pulpwood and palm oil firms say that their schemes are showing results, and are in line with zero-deforestation commitments many have made.

Since 2014, the area of burnt land on or near April’s concessions has fallen by 90 per cent, and the company has engaged with 77 communities across an area spanning more than 600,000 ha in Indonesia’s Riau province.

April’s bigger competitor, Asia Pulp and Paper (APP)—which was heavily implicated in the fires of 2015—runs a no-burn community engagement programme that has reached 307 villages. APP gives monthly cash incentives to local firefighting councils, called Masyarakat Peduli Api, if their villages stay fire-free, and works with communities to find sustainable alternative uses of land such as vegetable and fruit farming. The company has said it has spent US$150 million on fire prevention and suppression since 2015.

Satellite data seems to back up the companies’ claims. The number of hotspots in concessions is much smaller than the proportion outside company boundaries, and that percentage has fallen since 2015, according to data from Global Forest Watch (GFW). Less than a third of hotspots or fire alerts turn about to be actual fires.

GFW data also shows that, between June and September, about 1 per cent of fire alerts (2,342 out of 177,519 hotspots) occurred on APP supplier land, and less than 1 per cent (615 hotspots) on April supplier land.

Update, 22 September: A report from forestry information website Foresthints, which used data from Indonesian Environment and Forestry Ministry, found haze-causing forest fires in APP and April concessions.

A cheque for IDR 100 million (US$7,500) is awarded to village representatives living in a concession run by palm oil company Golden Agri-Resources in West Kalimantan. The award is for keeping their village fire free. Image: Eco-Business

Smallholders take the heat

This year’s haze, which began in earnest in July, has mainly been caused by smallholder farmers using fire to expand their plantations, suggested Carolyn Lim, senior manager of corporate communications for Singapore-headquartered palm oil company Musim Mas, which is a member of the Fire Free Alliance. The company works with smallholders to encourage sustainable agriculture as part of its no-deforestation strategy.

Anita Neville, senior vice-president, group corporate communications, for APP’s sibling palm oil company Golden Agri-Resources (GAR), said the current low price of palm oil has forced smallholders to scrimp on fertiliser, so many have resorted to fire to improve soil fertility. GAR’s no-burn community programme is called Desa Siaga Api.

Tackling slash-and-burn culture in Indonesia is “equivalent to getting people to wear seatbelts in cars or give up smoking,” said Neville, adding that many fires in community areas have been started by dropped cigarettes and neglected cooking fires.

“These behaviours will take more than three years to change. This is why GAR is extending fire awareness to schools in our most fire-prone areas and has been experimenting with WhatsApp messaging using gifs as a means of spreading messages of fire avoidance and prevention,” she said.

Fire prone

While smallholders are taking much of the blame for the haze, the big companies are responsible for large areas of peatland that are prone to fire. Last month, a drone study by green group Eyes on the Forest found that peatlands within APP and April-affiliated concessions designated for rehabilitation by the Ministry of Environment and Forestry after the 2015 fires had not been properly restored.

Both April and APP have said that the efforts of its affiliates comply with peatland management and restoration regulations.

Eyes on the Forest coordinator Nursamsu said that while the big pulp and oil palm companies may have largely put a stop to burning, they continue to drain peatlands in plantations. “This creates the ideal conditions for fires to start and spread in contiguous peatland areas,” he said.

Meanwhile, activists worry that a new regulation issued by the forestry ministry in July, which redefines the area of peatland eligible for protection, will make large areas of peatlands available for companies to cultivate. The regulation emerged a few months before Indonesia authorities said that 80 per cent of burnt areas could be turned into oil palm plantations or other industrial crops.

The search for scale

One idea to scale up corporate fire prevention schemes would be for more companies to combine their efforts, although the bitter rivalry between companies like APP and April could prove an obstacle.

April’s sustainability operations manager and chair of the Fire Free Alliance, Craig Tribolet, said his company’s programme is open to all, and has encouraged APP and other Sinar Mas companies to participate since FFVP’s founding, and “would value their imput”.

Bernard Tan, Singapore country president of Sinar Mas, APP’s owner, said it would be useful to first study the effectiveness of the programmes to learn which work best. APP plans to expand its fire programme to 500 villages by 2020.

Aidil Fitri, executive director of Hutan Kita Institute (HaKI), an Indonesian green group that protested against a proposed supplier for a massive new mill APP built in Sumatra in 2017, suggested that both companies should focus more on keeping peatlands wet rather spending millions on fire prevention. “Communities could receive incentives from companies for keeping their land areas wet, even during the dry season,” he said.

Syahrul Fitra, a researcher at non-governmental organisation Auriga Nusantara, said fire-free village programmes are not a substitute for a “fundamental shift” away from drained peatlands for agribusiness firms in Indonesia. “Details of the restoration work APP and April claim to have completed are not open to the public, so it’s impossible for civil society to verify whether progress is being made,” he said.

No-burn initiatives need to go hand in hand with peatland rehabilitation and protection, added Benjamin Tay, executive director of the People’s Movement to Stop Haze (PM.Haze), the green group member of the Fire Free Alliance whose work includes blocking drains and canals in the peatlands to re-wet the soil.

He pointed out that commercial crops such as acacia and oil palm are not well suited to grow on peatlands and, as long as they are planted on the swampy soil, will continue to cause problems.

“Unless we couple a firmer enforcement of policies for cultivation on peatlands and more scaleable rehabilitation programmes on degraded peatlands, we will be unable to free ourselves from haze in our region,” he said.