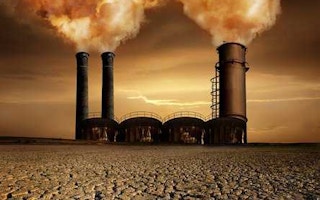

Inner Mongolia’s rivers are feeding China’s coal industry, and turning grasslands into desert. In India, thousands of farmers have protested diverting water to coal- fired power plants, some committing suicide.

The struggle to control the world’s water is intensifying around energy supply. China and India alone plan to build $720 billion of coal-burning plants in two decades, more than twice today’s total power capacity in the US, International Energy Agency data show. Water will be boiled away in the new steam turbines to make electricity and flush coal residue at utilities from China Shenhua Energy to India’s Tata Power that are favoring coal over nuclear because it’s cheaper.

With China set to vaporize water equal to what flows over Niagara Falls each year, and India’s industrial water demand growing at twice the pace of agricultural or municipal use, Asia’s most populous nations will have to reconsider energy projects to avoid conflict between cities, farmers and industry.

“You’re going to have a huge issue with the competition between water, energy and food,” said Vineet Mittal, managing director of Welspun Energy, the utility unit of Leon Black’s Apollo Global Management LLC-backed Welspun Group. “Water is something everyone should be probing every chief executive about,” he said in an interview.

Investors have driven up the 49-member S&P Global Water Index about 96 percent from its low point after the 2008 financial crisis, beating the 88 percent gain in the period by the 1,625-stock the MSCI World Index, a global benchmark.

Investor risk

“Power is a very good example of the risk investors can potentially face,” Giulio Boccaletti, a partner heading McKinsey’s water resource economics practice, said in an August 30 interview. “A problem with water can leave you with a stranded asset.”

China and India account for more than 60 percent of the world’s coal-fired power plants on the drawing boards by 2035, capable of producing about 805 gigawatts. China alone will consume 82 billion cubic meters of water a year by 2030, second only to the nation’s farmers, McKinsey & Co forecast.

More than half of existing and planned power plants by the biggest publicly traded companies in India and Southeast Asia are in areas likely to face water shortages, according to the World Resources Institute in Washington, which maps water risks for industries. Little data is collected by companies or their investors on what that means for projects with a 40-year lifespan, the US-based researcher said in a report.

’Peak water’

India’s power plants may be most vulnerable, the institute concluded after mapping more than 150 existing and planned projects in India and Southeast Asia. It found that 73 percent of capacity owned by three utilities — NTPC, Tata Power, and Reliance Anil Dhirubhai Ambani Group’s power units —is located in water-scarce or stressed areas. Overall, 74 gigawatts, more than half of India and Southeast Asia’s existing and planned capacity, face similar threats.

NTPC said in an e-mail response that its projects require a water commitment from state authorities for the full lifetime of the plant before they go ahead. It’s also using saltwater desalination at coastal plants to minimize fresh water usage.

Tata Power declined to comment. Reliance Power didn’t respond to two e-mails and telephone calls seeking comment.

“The world has already hit ’peak water,”’ says Simon Powell, head of Asian oil and gas research at CLSA in Hong Kong. Demand is growing against a finite supply of fresh water that’s shrinking due to pollution and climate change, he said.

Global water demand may have already outstripped supply in 2010. The world’s freshwater requirement in 2010 was estimated at 4.5 trillion cubic meters compared to an accessible supply of 4.2 trillion cubic meters, according to McKinsey & Co.

Water assumptions

Coal is currently running more than 40 percent of the planet’s electricity generation plants, which consume on average three times as much water as natural gas-fired stations per unit of power produced, according to US Department of Energy data. Nuclear plants use even more water than coal units.

Beside needing water to produce steam, it’s also used in condensing and to process waste deposited in ponds. Water is used in coal mining to remove impurities and transport the fuel through pipelines as slurry.

Some of the water can be recycled or discharged back to its source. However, a shortage can shut a plant or force it to compete for farming and drinking water.

Utilities “assume the water is there,” Peter C Evans, director for global strategy and planning at General Electric, the biggest maker of power-plant turbines, told a conference in June in Tokyo. “They actually will not be able to build as many coal plants as the projections suggest.”

Ground zero

Grasslands drying up in Inner Mongolia is caused by coal mines and power plants taking from rivers, said an August 14 study by China’s Institute of Geographical Sciences and Natural Resources Research commissioned by Greenpeace. The region holds less than 2 percent of China’s water and by 2015 will host about triple the European Union’s coal-fired capacity, it said.

Ground zero in India’s fight for water may be along the 560-mile stretch of the Mahanadi river in the coal-rich states of Chhattisgarh and Odisha, where paper mills, steel plants and mines mostly powered by coal plants flank the river’s banks.

The state governments have signed agreements for at least 49 coal power plants with a combined 57.5 gigawatts of capacity, according to Ravi Shekhar, a power industry consultant at New Delhi-based Infraline Energy Research and Information Services. That’s more than Japan’s coal-fired plant capacity, according to IEA figures.

“The allocation of water for these industries is irrational,” says Infraline analyst Simran Jeet Singh. “They allocate without any planning.”

Thousands protest

Farmers in India have blocked highways and railway lines, sometimes committing suicide, to protest coal plants under construction that they fear will drain rivers and choke off irrigation water.

On August 27, three thousand villagers protested against a 1,320-megawatt coal plant planned at Pitamahul, one of many demonstrations along the Mahanadi, says Ranjan Panda, an activist with Water Initiatives Odisha. Irrigation projects are stalling and villages are being displaced, he said.

“This river is a lifeline and every stretch is either already being used by industry or has been committed,” he says.

Companies building coal plants and their lenders say they’re taking precautions to ensure water supply. When projects are planned, rights to fuel and water are among the permits obtained before a project is approved.

“When someone comes to me with a project proposal, I will make sure that the water is available, adequate water,” Satnam Singh, chairman of Power Finance, India’s largest lender to electricity utilities, said in a June interview. “Water is not going to become zero.”

Straining rivers

Yet there are signs authorities are granting more water rights than rivers can sustain.

In April 2010, Maharashtra State Power Generation shut down 90 percent of its 2,340-megawatt power station in Chandrapur about 520 miles east of Mumbai after low rainfall caused water levels to plummet at the Erai dam, according to a letter sent by the utility to the electricity regulator.

The same plant is now in the midst of a 1,000-megawatt expansion and another 7,000 megawatts of coal-fired plants are planned in the area, according to Infraline’s Singh.

In 2009, Beijing shut 49 factories and moved some power plants and steel factories to the coast because of a lack of water, Maxime Serrano Bardisa, water analyst for Bloomberg Energy Finance in London said in a July 2 interview.

In April, India’s Oil & Natural Gas closed an oil refinery, another water-intensive industry, when levels dropped in the Nethravathi river in southern Karnataka state.

Lack of fuel

The Indian government also has a track record of reneging on its promises on another essential supply: fuel. India’s coal power industry has delayed or canceled about 1.9 trillion rupees ($34 billion) in projects because of production shortfalls at state-controlled Coal India and a rail system that can’t move enough cargo, according to data from the Association of Power Producers.

CLP Holdings, Hong Kong’s biggest electricity supplier, passed on an opportunity to build a new coal plant in Odisha state because of concerns about water, Naveen Munjal, director of business development, said in a June interview. CLP was stranded this year with a 1,320-megawatt coal plant in Haryana that’s “dead cold” for lack of fuel supplies, he said.

Usage not disclosed

Investors and analysts often aren’t equipped to gauge such risks because of a lack of publicly reported information. Only one electric utility in Asia, Korea Electric Power, discloses its total water usage, according to environmental disclosure data compiled by Bloomberg.

“Even if the water is perfectly available and abundant right now when that plant’s permit is issued, a lot can happen in 30 years,” Robert Kimball, an associate at the World Resources Institute, said in an August 27 interview.

As such risks come to light, financing may become more difficult and expensive, the World Resources Institute’s Kimball said. Every 5 percent drop in a power plant’s average output caused by water shortages results in a nearly 75 basis point drop in the project’s internal rate of return, according to an analysis by HSBC Holdings Plc.

“The challenge with water data is that it’s actually quite tricky to measure and hard to understand,” says McKinsey’s Boccaletti.

GE is developing a global model to better understand the power sector’s water consumption. Goldman Sachs Group, GE, Bloomberg LP and others are funding a World Resources Institute project to release maps this year showing industry-specific water risks. The Coca-Cola has donated data.

Renewables benefit?

“The data just isn’t sitting around. So we have to create new data in order to analyze this issue,” GE’s Evans said.

Bloomberg LP is the parent company of Bloomberg News. Former US Vice President Al Goreis a board member of the World Resources Institute as is Bloomberg President Dan Doctoroff.