Asia is home to a worsening water pollution crisis thanks to an accelerating but weakly regulated industrial boom, but its most vulnerable citizens are kept in the dark about whether the water they use for drinking, farming and fishing is safe, a new report by think tank World Resources Institute (WRI) has found.

To continue reading, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

Titled ‘Thirsting for Justice: Transparency and Poor People’s Struggle for Clean Water in Indonesia, Mongolia, and Thailand‘ and released on August 30 at the World Water Week in Stockholm, the report found that despite the fact that the governments of the three countries studied are legally required to be transparent about water quality information, they are flouting these laws.

This has dire implications for the health of impoverished rural communities and their livelihoods, added WRI, which conducted the research as part of its Strengthening the Right to Information for People and the Environment (STRIPE) programme.

The non-profit organisation, headquartered in Washington DC, analysed data from environmental status reports, water quality monitoring portals, and other public data bases to gauge the degree to which governments are releasing information about water pollution, and the companies that cause it.

It also spoke to 150 individuals and tracked 174 information requests submitted by the community to assess how these legal requirements play out.

The findings showed that there is extensive legislation requiring governments to proactively release environmental information as well as fulfil Right to Information requests. Much of this is driven by the adoption of international standards on public disclosures into national law.

WRI found that all three countries have requirements to disclose the general quality of water bodies, health impacts of pollution entering the water, and what they are doing to clean up water sources.

However, laws around reporting indicators such as the consequences of using contaminated water, information about companies polluting the water and the level of discharge that companies can release, varied among the three countries.

The common means by which governments communicate this information to the public are state of the environment reports, environmental impact assessments, permitting registers, environmental disclosure ratings, pollutant release and transfer registers, and data portals.

When it comes to laws about heeding right to information requests on environmental issues, Thailand and Indonesia legally require their governments to release documents about pollution impacts, facilities, and water monitoring information to communities; Mongolia only has laws around the release of radioactive or poisonous substances.

While the legal provisions are broad, there is a lack of clarity around exactly how the information should be made available to communities, observed WRI.

“

Governments’ failure to provide water pollution information is an environmental injustice. Without it, poor, marginalised communities cannot participate in decision-making, let alone hold governments and more powerful corporations accountable for contaminating their local water sources.

Elizabeth Moses, environmental democracy specialist, World Resources Institute

Communities left high and dry

As extensive as the legal requirements around water pollution transparency are, WRI found that officials are failing to put these laws into practice. In Indonesia and Mongolia, for instance, bureaucrats ignored 58 and 59 per cent of information requests, respectively.

Elizabeth Moses, environmental democracy specialist at WRI and the report’s author, said in a statement that “governments’ failure to provide water pollution information is an environmental injustice.”

“Without it, poor, marginalised communities cannot participate in decision-making, let alone hold governments and more powerful corporations accountable for contaminating their local water sources,” she added.

One community that has been adversely affected by poor information about water pollution is the Map Ta Phut zone in Rayong Province, Thailand. The area is home to five industrial estates, one deep-sea port, and 151 factories including petrochemical plants, oil refineries, and coal-fired power stations.

Despite the high levels of pollution associated with these activities, communities living in the area allege that the authorities are not only allowing pollution violations to occur on their watch, they are also failing to inform people about pollution-related incidents.

The report adds that the local community has requested a list of factories that do not comply with environmental laws from the government, along with the specific pollutants being released and their health impacts.

But while the government has released some information such as the locations of factories releasing pollutants into the river, it never released a list of factories violating the law, or details about the health impact of pollutants.

What little information was released was either in English, which most locals do not speak, or highly technical and difficult to understand, WRI observed.

Nangsao Witlawan, a Map Ta Phut resident and former oil refinery worker, said: “All the government services municipalities, public health, the Office of the Natural Resources and Environmental Policy and Planning, and the Industrial Estate Authority of Thailand realise what has been happening with pollution in our community, but they don’t tell or give us the true information.”

Witlawan, who also has stage four cervical cancer, added: “I’ve never received correct and clear information about the water.”

The report documented similar issues in Indonesia and Mongolia.

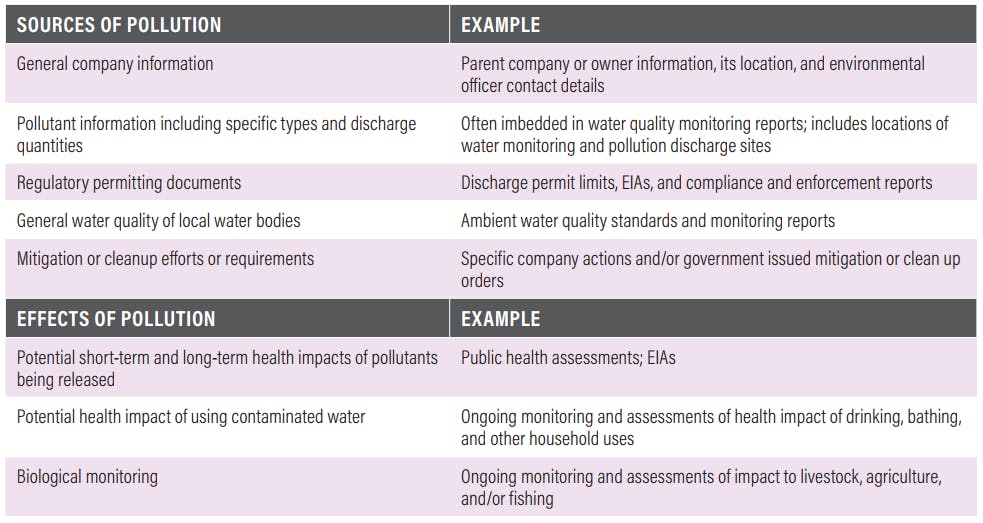

Types of information about water pollution that communities need. Image: World Resources Institute

Reform needed

WRI recommended a slew of measures to address this major information gap. Chief among them is the development of a centralised system that collates data from national and sub-national agencies reporting on water quality issues, and serves as a single point of information for communities.

Governments in these countries should also take care to ensure that data is released in a format and language that communities can understand through means such as community information centres, guidebooks, simple signs and radio alerts, and work closely with locals to get a better sense of the types of data that people want, and how they prefer to access it.

Collaboration with the private sector and state-owned companies can help policymakers improve on transparency efforts, said WRI. It went on to urge community members and civil society to become more engaged in water quality issues, build capacity on how to demand better information from the government, and engage in policy discussions.

Lastly, international donors that are focusing on water issues should make more resources available to civil society and governments to help them improve how information is communicated to communities, and used by people.

John Knox, the United Nations Special Rapporteur on Human Rights and the Environment, said in a statement that ultimately, “people have the right to know about hazardous pollution in the waterways on which they rely”.

“Governments that fail to provide that information are violating their citizens’ human rights,” he added.