Last week, Zhang Shangchen, a 22-year-old PhD student from China’s Tsinghua University, went door-to-door at delegates’ offices at the COP27 global climate summit in Egypt, to invite them to a youth dialogue. Of about 10 delegations who answered, only three turned up for the event hosted by a global group of university students.

To continue reading, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

Jose Villalobos, 24, a campaigner from Chiapas, southern Mexico, has been asking for meetings with Latin American negotiators on issues like climate debt. He only managed to get a tentative yes as an answer from the decision makers.

“We’ll see,” Villalobos said, on whether a meeting would eventually take place.

As thousands of youths descend upon the Red Sea resort town of Sharm El-Sheikh for the annual climate gathering, they bring calls for greater inclusion of young people at negotiating tables and warnings of dire risks their communities face as global warming continues unabated.

The Egyptian presidency for COP27 has said that youth participation is an integral part of climate action. It prides itself on hosting the first children and youth pavilion, a side-event space where young people organise talks on climate justice and education. Both Sameh Shoukry, Egypt’s COP27 president and Alok Sharma, host of last year’s Glasgow COP26 summit, have visited the pavilion.

However, young campaigners say getting their voices heard and their asks registered in negotiations remains a challenge. Their participation feels tokenised at times, they say, while logistics woes have prevented more peers from attending in person.

Isabelle Zhu-Maguire, an advocate with the Australia, New Zealand and Pacific arm of the United Nations-aligned Sustainable Development Solutions Network, said that there seems to be “two distinct conversations” at the climate conference happening in parallel.

“There are these high-level people saying, we are listening to you, we are doing new things. But often we feel really disenfranchised,” the 23-year-old said. Zhu-Maguire hosted a workshop last Wednesday on the topic of “youth-washing”, where governments and firms use youths’ voices to gain traction for their own agenda.

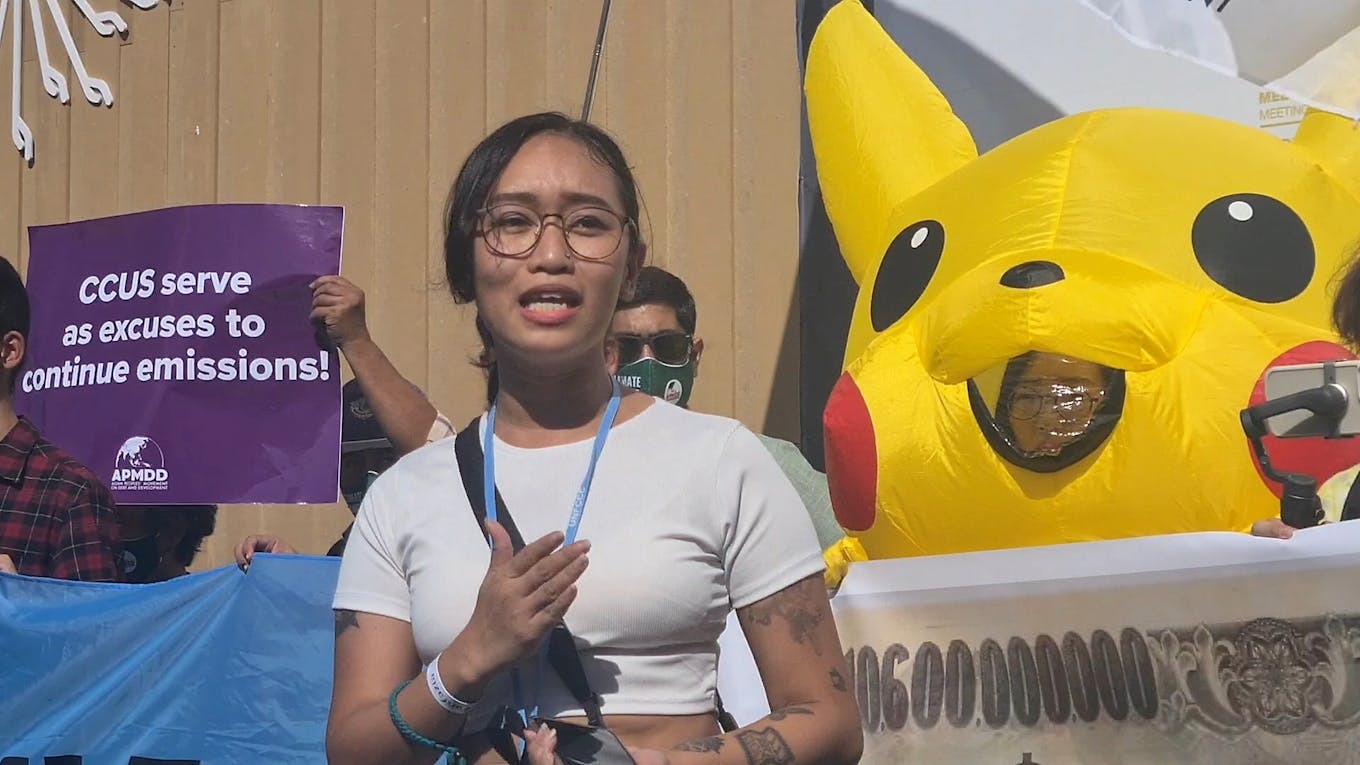

Krishna Ariola, a climate activist from the Philippines, speaking at a fossil fuel protest at COP27. Image: Eco-Business/ Liang Lei.

Krishna Ariola, 25, a campaigner with the Philippines-based research institute Center for Energy, Ecology and Development (CEED), said that in her experience, youths from Philippines and other countries vulnerable to climate disasters have often been invited to speak about their experiences as victims.

“We are not just victims. The people in our communities are also at the frontlines of fighting back against corporations, against carbon majors,” Ariola said. She had been part of protests against fossil fuel financing in the past week.

Starkly missing at COP27, however, are the mass street protests common in the climate summits of recent years. For example, at COP26, there was a thousands-strong street march. This time round, the spaces allowed for demonstrations are much smaller, with few areas outside the summit venue available.

Selma Bichbich, 21, a climate activist from Algeria, said that the small scale of allowed demonstrations at COP27 amounted to “protesting just for the sake of [showing] there are protestors”. It had made her rethink whether to go ahead with some demonstrations she had been planning.

Villalobos said his switch from protests, which he had been part of in past years, to trying to engage with negotiators is also in part due to the restrictions on rallies at COP27.

“We need to change our strategy. We need to do political work,” he said.

Rising opportunities

More opportunities have been opening up for youth participation in climate talks over the years. For instance, the United Nations Secretary-General, Antonio Guterres, has a seven-member youth advisory group on climate change. Members have direct contact with the global body’s chief, and are given opportunities to speak at high-level events at COP summits.

“It is an incredible opportunity,” said Sophia Kianni, 20, a member of the youth advisory group from the United States.

Sophia Kianni, 20, a member of the United Nations Secretary-General’s youth advisory group on climate change, poses for a photograph at the Children and Youth Pavilion at COP27. Image: Eco-Business/ Liang Lei.

“My hope is to call world leaders out and hold them accountable, and hopefully get them to take action,” Kianni said of her participation at COP27.

There is also YOUNGO, a network of youth groups in the umbrella of the United Nations climate change office. YOUNGO has been holding a Conference of Youth immediately before COP summits for years, and since 2021, it has been publishing a Global Youth Statement reflecting the group’s collective demands.

This year, the 107-page statement detailed key asks on issues like climate adaptation, finance, energy, arts and culture, as well as biodiversity. Each subsection has suggestions on how the youth can be better involved.

But youths, after attending climate summits, also need to be able to return home to a government that hears them out, said Bichbich. She recalled how after a youth climate conference in Milan last year, European youths went to the European Council to voice their ideas, but participants from Africa and the Middle East could not find an equivalent platform.

The issue could also lie with how youths themselves understand their role, she said.

“They don’t know that we do have this right to draft things, to propose things for our country. The fact that we don’t know, that is an issue,” she said, adding that encouraging more youths to take action is one of her key aims at COP27.

Xan Northcott, 27, the Global North Focal Point coordinator for YOUNGO, said that the group will push to get more data on which countries have youths as part of their national delegations at COP27.

Youth delegates need to be involved in negotiations beyond youth issues, Zhang said. If not, it becomes a case of “we hear you, but that’s all”, he said.

Neither should age be seen as an issue, said Samson Cheng, another member of the Global Alliance of Universities on Climate that Zhang is leading. Cheng pointed to the credentials of the alliance’s members, which includes professionals in urban planning and environmental management.

There are also efforts to train youths up to shoulder such responsibilities. Future Leaders Network, a non-profit based in the United Kingdom, runs a Climate Youth Negotiator Programme that provides a six-month crash course on climate negotiations. Some of the programme’s graduates, from countries like Peru and Nepal, are already in the thick of the action at COP27.

In other instances, young activists are invited to COP27 under a national party badge, like in the case of 21-year-old Terese Teoh, an undergraduate from Singapore who is part of a climate advocacy group, Singapore Youth for Climate Action.

“Before I came to COP27, there was a lot more worry about how having a party-overflow badge might limit my experience,” Teoh said, but she added that she felt free to do and say whatever she liked once she was at the summit. Party-overflow badges tag participants to their countries but not their negotiating teams. Most activists register under “observer” badges, which tags them to their organisations instead of country.

Teoh was part of a Singapore-hosted event on youth advocacy early last week, where the panel discussed the workings of activism in the city-state. She told Eco-Business she stays connected to activist groups in Singapore to avoid being influenced too much by the Singapore government position.

Teoh had helped to craft a policy paper ahead of COP27 detailing the asks of climate activists in Singapore, including stricter carbon tax rules for fossil fuel firms and greater clarity on the city-state’s 2050 net-zero target.

Youths attend a daily meeting on November 8 organised by YOUNGO, a network of youth groups under the United Nations climate change body, at COP27. The group meets daily during the climate conference to update on their work plan and provide help for youths who want to hold events or meet with country delegations. Image: Eco-Business/ Liang Lei.

Logistics nightmare

One of the biggest challenges in attending COP27 had been the sheer prices of getting to and lodging in the Red Sea resort town of Sharm El-Sheikh, where the conference is held, youths told Eco-Business.

Hotel prices during the COP27 period rose to hundreds of dollars at many establishments, leading to accusations of price gouging.

Ariola, representing CEED from the Philippines, said she initially managed to secure a hotel room at around US$68 per night for two weeks, but was told to pay 50 per cent more on arrival. CEED managed to help her settle the top-up, but Ariola noted that the total amount asked, at over US$1,300, was easily two months worth of salary back home.

Villalobos, the climate activist from Mexico, said he bunked in with friends for the first three days for free, before managing to find a hotel that had a rate he could afford, at US$61 per night. Eight youths from Mexico were supposed to attend COP27 together, but because they could not raise enough funds, three could not travel, Villalobos said.

“It is another [sign] that COP27 is not working. If young people don’t have the money to come, how is their voice going to be present here?” Villalobos said.

The COP27 organisers have, in September, announced subsidised accommodation for up to 400 youths, reported to be at US$30-40 a night. But youths told Eco-Business some have had to wait for hours for such rooms upon arrival.

There should be more funding provided for youth participation, youths say, especially for those from poorer countries.

“Businesses and fossil fuel companies can afford to send hundreds of people here to COP27, and they do, whereas young people do their climate work unpaid, voluntarily, on top of their jobs or university studies, so it is really tough,” Northcott from YOUNGO said.

Non-profit Global Witness found last week that 636 fossil fuel lobbyists have been granted access to COP27. Meanwhile, YOUNGO itself had to fundraise to send its members to the summit, with donations from the UK government and various United Nations agencies.

Many youths who did make it to COP27 also told Eco-Business that the difficulties have strengthened their resolve to make the most of the occasion.

“It is so sad that I’m living in this era where [the previous generation] did not do enough for us. I don’t want to do the same for the upcoming generations,” Bichbich said.