Twenty years ago, the city of Tirana in Albania was dull and bleak, with drab, dilapidated buildings and streets menaced by crime. But today, residents are proud to call the city home and its streets are no longer the same desolate sight.

The change came when Edi Rama, the mayor of Tirana between 2000 and 2011, implemented a series of reforms to paint the city’s buildings in bright, vivid colours, which helped Tirana turn a corner to see a drop in crime and littering.

According to theories in sociology and criminology, people take cues from their physical environment about how to behave. Graffiti and litter can encourage more anti-social behaviour. On the other hand, the neater, more beautiful and well-maintained a city, the better its people behave.

“Colour changes your mood, your emotion and it makes you feel different. Imagine if the whole city is grey rather than colourful—that will have a very different effect on your personality,” says Jeremy Rowe, managing director of decorative paints for South East Asia, South Asia and Middle East at paints and coatings firm AkzoNobel.

The Dutch multinational would know; as part of its Let’s Colour programme, AkzoNobel turned underused urban spaces in Rio de Janeiro into sport courts with the help of paint, breathing life into favelas and creating room for Brazilian youths to enjoy basketball, table tennis and volleyball.

But paints can do more.

Painting the town green

Traditionally, cities have used blue paints and coatings to keep cool during the summer months, such as in the Moroccan city of Chefchaouen and the Blue City of Jodhpur, India.

Today, building developers use modern paints with enhanced heat-reflecting capabilities to reduce indoor temperatures, reducing the need for air conditioning and generating energy savings for tenants and facility managers alike, says Rowe.

For instance, AkzoNobel’s Weathershield KeepCool coating is able to make a building’s surface temperature at least 5 degrees Celsius cooler, which translates to a saving of up to 15 per cent in cooling costs. In turn, this results in less electricity use and reduced carbon emissions for the planet.

Despite the potential energy savings, convincing building owners to invest in such multifunctional paints remains a challenge because paints may not yield immediate returns, according to industry insiders.

The team is accustomed to demonstrating the energy-saving potential of the company’s products to building project managers. AkzoNobel’s laboratory tests demonstrate the temperature-reducing effects with artificial light, building simulations show how this translates into savings, and in-use tests on real buildings with temperature sensors prove that the products work in real-world settings.

“Normally, this is enough to show building project managers that they will get real results,” says Rowe.

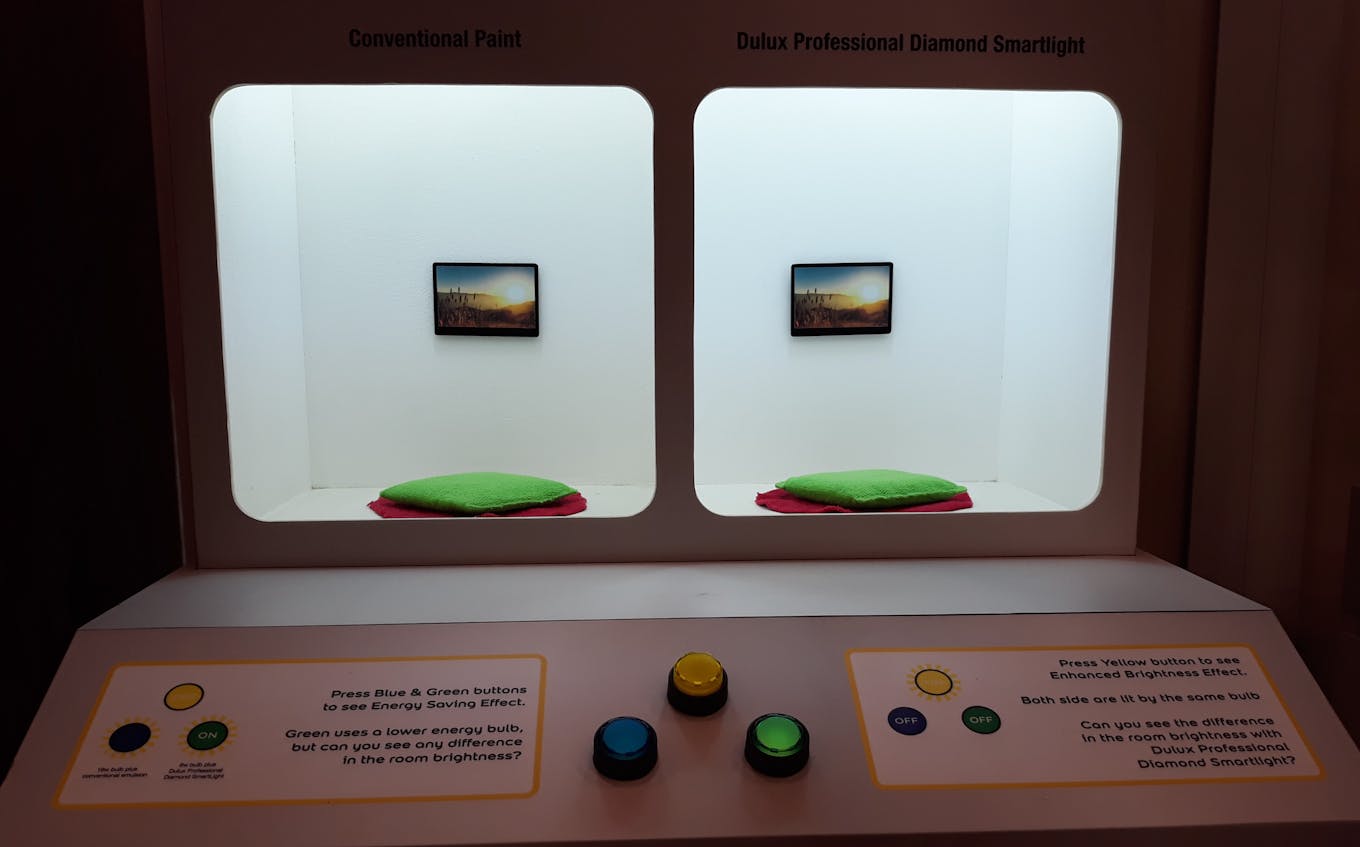

Besides external coatings for buildings, AkzoNobel also manufactures light-reflecting paints for indoor use, which means less electricity is needed to achieve the same amount of illumination, Rowe explains. “[It] means you can use lower voltage lightbulbs, so you save energy.”

Prototype in AkzoNobel office demonstrating that rooms coated with light-reflective paint (right) are brighter than rooms coated with conventional paint (left). Image: Eco-Business.

Constant product innovation has allowed AkzoNobel to develop more durable and resource-efficient paints. “The average repainting cycle for Singapore’s public buildings is five years. If we can make that product last seven years or 10 years, you stretch the repainting cycle,” says Rowe.

Typically, three coats of paint—one sealer and two top paints—are needed in any paint job, but AkzoNobel has been able to achieve the same performance with only two coats. This means less resources are used to do the same job, which means not only a smaller environmental footprint but also automatic savings on “one third of the labour time of the [painting] project”.

Less widely known to the regular joe on the street are powder coatings, which are sustainable, solvent-free paints applied as a powder onto surfaces and then baked to set. Because powder coatings do not contain solvents, they do not release pollutants known as volatile organic compounds into the air during application, says Rowe.

Powder coatings can be applied in a single coat and excess powder can be collected and reused, reducing waste generated as a result. AkzoNobel is the world’s largest producer of powder coatings, and its product has a much lower carbon footprint compared to alternatives in the market, he adds.

Support for eco-friendly paints

Both the influence of international developers, who are more “progressive in their use of sustainable products [compared to local developers]”, and the support from the local government play a major role in the adoption of sustainable coatings, comments Rowe.

In Singapore, a building’s ability to reflect heat is integrated into the Building and Construction Authority’s Green Mark rating system, a cumulative point system that classifies buildings into different tiers of eco-friendliness. This has improved developers’ awareness of the need for good coatings, says Rowe.

Commenting on Singapore’s green policy frameworks that support the adoption of sustainable coatings, he says that “other countries are seeing what’s going on in Singapore and using that for inspiration, because [Singapore has one of] the most progressive of systems, along with Europe, China, Australia.”

Moving forward, the Dutch company wants to make the prices of its eco-friendly coatings, which cost more than conventional paints, more affordable and accessible, says Rowe.

AkzoNobel will also continue to look at how paints can help tackle urban sustainability issues, such as air pollution. Rowe reveals: “We are looking at developing air purification and air cleansing [functions for paint]. We will continue to see how we can improve the indoor air quality of buildings and potentially outdoor air quality as well.”