How environmentally friendly is the coffee you drank this morning? The clothes you’re wearing? What are the social impacts of the chair you’re sitting on? Perhaps you’ve tried to find the answers to questions like these from retailers, but got no response, or just a vague “commitment to sustainability” statement?

A desire for products to be clean and green rather than drive climate change, wildlife destruction or modern slavery is a growing trend, particularly among younger consumers. But shopping ethically is often more easily said than done.

A poll of 20,000 people across five countries by consumer goods company Unilever last year found that 33 per cent of respondents choose to buy from brands they believe are doing social or environmental good, with 21 per cent saying they would actively choose brands if they made their sustainability credentials clearer on their packaging and in their marketing.

At the same time, many people are increasingly skeptical of claims made by media, politicians and business. A 2016 survey by product transparency company Label Insight found that 75 per cent of respondents did not trust the accuracy of food labels.

An increasing number of business leaders are realising that they need to find a way for consumers to verify their product’s story. If a consumer can use a smartphone app to discover what country a product came from, what certifications it holds and even the name of the farmer or miner who produced it, those business leaders believe, that product will not only have the edge over others, but also reduce adverse environmental and social impacts of supply chains as ethical companies gain market share over those that are not.

“

If your business is not doing this and is still hiding behind an opaque supply chain, then you will lose business.

Edward Mendelson, project lead for sustainable supply chains, Everledger

Benefits of blockchain

Blockchain technology is emerging as a powerful way to do this. Best known for being the programming protocol behind cryptocurrencies such as Bitcoin, blockchain is essentially a digital ledger. Information is held not by a central authority or organisation, but in an encrypted, distributed computer network, making it secure and shareable. The technical explanation is complex, but experts say blockchain essentially makes data tamper-proof, so it cannot be erased or manipulated by any one party.

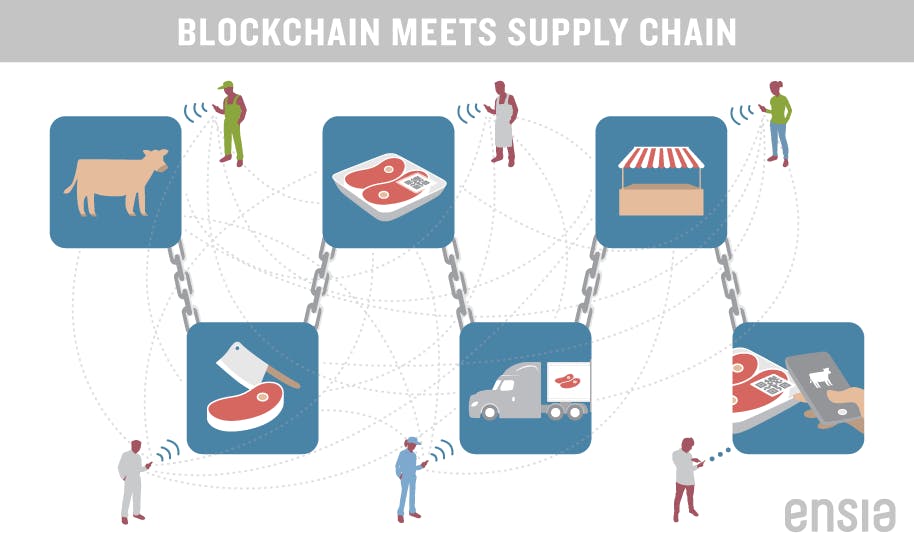

Say a food company wanted to be able to convince you that its meat was produced in a way that meets benchmarks for animal welfare and sustainable agriculture. It could set up a blockchain platform that each member of its supply chain could view and upload information to.

Each participant in the chain would submit the information for its respective part in the process to the blockchain as a block of data—be it raising the animal, butchering it, or packing, transporting or selling the meat. Selected parties in the supply chain, as defined by the contract, would each see an encrypted code that represents the block of data added.

If all agree they are seeing the same code, then the information is deemed accurate and written to the blockchain — that is, included as part of the verified description of the product. This process, called “consensus,” ensures accuracy and maintains whatever level of trust was originally bestowed on the members of the blockchain without the need to share the actual data with everyone on the blockchain.

Only the direct parties that are trading together, such as a processor sending packaged meat to a retailer, will see the actual information for their transactions. (With one exception: a regulator could see all the information on the blockchain.)

The information would be embedded in a QR code on the meat’s packaging, which consumers could scan with a smartphone app. They would then be able to see who raised the animal, how it was raised, how many animals were raised in its batch, who the butcher was and how the animal was butchered.

Blockchain can help a food company assure customers of the sustainability of a product by allowing each member of the supply chain to input a claim as to how it managed its step of production and then allowing other supply chain members to verify that the information was supplied by a trusted member. Illustration by Sean Quinn | Ensia. Click to expand.

“Using blockchain technology helps us authenticate a product’s story,” says Cody Hopkins, general manager of Grass Roots Farmers’ Cooperative, an Arkansas-based meat company. “It’s not just us as a brand typing in the information, it’s actually an ecosystem of users, who each have their own account on the platform where the transactions are verified by consensus.”

The cooperative uses a blockchain platform developed by UK-based tech group Provenance to give customers information about the animal welfare and environmental standards used in the production of its meat.

“The information logged on the blockchain is then publicly available and cannot be changed. It’s a really exciting way to tell our story,” Hopkins says.

Leading Finnish food retailer S-Group has teamed up with tech giant IBM to trace information on the origin of its pike perch, a popular fish in the country. By scanning a QR code on the fish’s packaging, shoppers can find out the lake the fish was caught in and what methods were used to catch the fish.

“This is a great way of raising awareness of discussions around what we should eat and where it should come from,” says Tomi Lehikoinen, retail executive at IBM.

Blockchain technology allows consumers to use their smartphones to identify the lake of origin for fish they buy from S-group, a Finnish retail cooperative. Photo courtesy of Vince Smith

In the Southern Hemisphere, teams from the conservation organisation WWF in Australia, Fiji and New Zealand have teamed up with tech companies ConsenSys and TraSeable and tuna fishing company Sea Quest Fiji to develop blockchain traceability of tuna. The system is expected to allow consumers to, using a smartphone app, check where a fish was caught and what fishing method was used. The team is now signing up more partners and scaling up the project for wider industry adoption.

Other companies started using blockchain for reasons other than tracing the environmental and social impact of supply chains, but have now moved into this area.

Digital traceability technology company Everledger initially used blockchain to prevent insurance fraud in the diamond industry. But consumer demand for proof that the jewels were not driving conflict and, more recently, information on their carbon and energy footprint, caused it to expand its focus to sustainability, explains Edward Mendelson, Everledger’s project lead for sustainable supply chains. The company also now traces the supply chain of coloured gemstones, metals and minerals using blockchain, Mendelson says.

Global diamond giant De Beers is also working on a blockchain-enabled platform called Tracr to involve companies across the diamond supply chain in providing information. So far, it has five manufacturers and jewellery retailer Signet on board and hopes eventually to provide the information to consumers.

Still a role for certification

One challenge facing use of blockchain to verify claims about supply chains is that it can show what inputs go into making a product, but it can’t prove to a consumer that those inputs have low environmental or social impact. For that, auditing and certification, and accurate data inputs, are still needed.

“Blockchain is useless at telling you if something is organic or not. You need an auditor or certification for that,” says Jessi Baker, founder of Provenance. “But it means that you can’t duplicate a record and claim to have more organic products than you have. It creates a single source of truth for that product.”

The US-based Organic Soil Association is using blockchain to back up claims that products are not genetically modified and are free of artificial preservatives. Photo courtesy of Provenance

Dave Rejeski, director of the technology, innovation and the environment project at US-based Environmental Law Institute, sees opportunities for improving the certification process as well. “At some point we may be able to use machine learning and other artificial intelligence tools to automate this, from satellite imaging for instance,” he says.

Ultimately, blockchain-based networks could be self-governing, Baker believes. “If a supplier lied, there would be a massive incentive to call them out because the network is owned by its participants, and they won’t want the network to devalue,” she says.

Other challenges facing the nascent application of blockchain to supply chain authentication include technology immaturity, low consumer awareness of blockchain and lack of industry standards.

“I am generally concerned with the larger issues of scaling and interoperability that are hard problems to solve across supply chains and often require years of negotiations between multiple organizational bodies,” Rejeski says. “The insurance industry has set up a consortium to work on blockchain interoperability standards, and I think similar efforts will be needed to tackle environmental challenges.”

Despite those challenges, blockchain continues to advance—and in some cases is becoming the norm—as a tool for ensuring supply chain integrity.

“If your business is not doing this and is still hiding behind an opaque supply chain,” Mendelson says, “then you will lose business.”

This story was written by Catherine Early and published with permission from Ensia.com