On 30 May, the Monetary Authority of Singapore announced that it will be including specific criteria for the managed phase-out of coal-fired power plants in the Singapore green taxonomy, and will be launching a consultation on draft proposals within the next few weeks.

To continue reading, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

This means that the final version of Singapore’s taxonomy, which was supposed to be published in June this year, might be pushed back for market participants to study the additional criteria for coal phase-out.

The decision to include coal phase-out in the city-state’s taxonomy came about in response to growing calls for financial institutions to stop funding the world’s most polluting fossil fuel.

What is a green taxonomy?

A green taxonomy is a classification system used to determine whether an investment or activity is sustainable.

A well-designed green taxonomy will set out the objectives, sectors and activities that are in scope for sustainable business activity.

Metrics and thresholds that set out how activities can be classified as green or transitioning to the next level of alignment with environmental objectives provide guidance to financial institutions.

This supports the provision of transition finance to the broader economy, and facilitates the move towards a cleaner and greener economy.

A green taxonomy can also help to prevent greenwashing. Companies can no longer use their own metrics to hoodwink consumers into thinking that their products are greener than they really are.

Which countries have a green taxonomy and how do they differ?

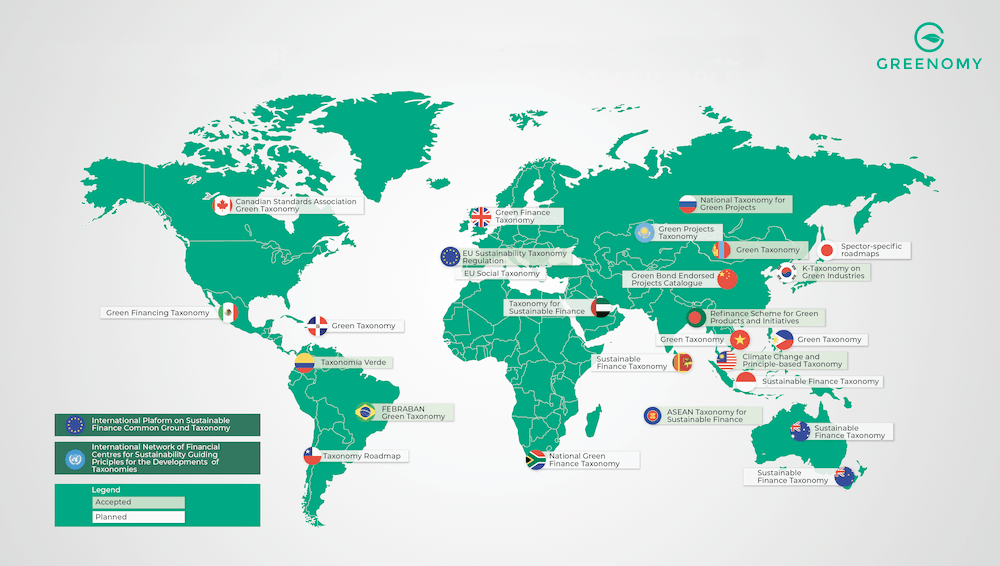

The EU Taxonomy is a reference point commonly used by countries in designing their own green taxonomies. Image: Greenomy

In the wake of the wide-reaching taxonomy released by the European Union (EU) in 2020 that is regarded as the most comprehensive sustainable finance taxonomy to date, many countries have started working on their own taxonomies.

Indonesia, Sri Lanka, and Kazakhstan, among other countries in Asia, have finalised their taxonomies.

Latin American countries have also been working on taxonomies that fit their own local contexts: Colombia was the first country in the Americas to launch a green taxonomy in 2022, and other Latin American countries are following.

Other regional taxonomies like the Association for Southeast Asian Nations (Asean) Taxonomy, have also been developed. Meanwhile, joint taxonomies, such as the Common Ground Taxonomy (CGT), have attracted attention from international capital markets and policymakers. The CGT provides a comprehensive mapping and comparison between the EU and China’s taxonomies.

Green taxonomies differ in their environmental objectives and the assessment criteria used.

For example, the EU Taxonomy has six environmental objectives: (1) Climate change mitigation; (2) Climate change adaptation; (3) Sustainable use and protection of water and marine resources; (4) Transition to a circular economy; (5) Pollution prevention and control; and (6) Protection and restoration of biodiversity and ecosystems.

On the other hand, the Asean Taxonomy shares four of the six environmental objectives of the EU Taxonomy but does not share the two following objectives: (3) Sustainable use and protection of water and marine resources and (5) Pollution prevention and control.

The EU Taxonomy uses three criteria to determine whether an activity is “environmentally sustainable”. They are: (1) Makes a substantial contribution to one of the six environmental objectives and meets relevant technical screening criteria (TSC); (2) Do no significant harm to the other five environmental objectives and meet relevant TSC; and (3) Comply with minimum safeguards.

The Asean taxonomy, the second version of which launched this March, uses a similar set of criteria as the EU Taxonomy, but with an additional criterion: (4) An obligation to avoid causing social harm (newly incorporated in Version 2 to highlight the importance of social aspects in the Asean Taxonomy).

Taxonomies also differ in the business activities and sectors included.

Bangladesh’s taxonomy contains 52 activities in eight categories eligible for green financing. China’s taxonomy, on the other hand, covers more than 200 activities.

The third way in which green taxonomies differ is the type of classification system adopted.

Singapore and Indonesia’s taxonomies have a “traffic light” system for classifying activities as green (environmentally sustainable), amber (transition), or red (harmful). The Asean Taxonomy adopts a similar colour-coded classification system.

Binary taxonomies such as the EU Taxonomy simply classify whether or not an activity is green. It also includes transitional activities for which low-carbon alternatives are not yet available.

What are the benefits of a regional taxonomy?

Sumit Agarwal, managing director at the National University of Singapore (NUS)’s Sustainable and Green Finance Institute (SGFIN), says that the biggest benefit of a regional taxonomy is that it provides a common language for companies and investors to communicate sustainability performance.

A regional green taxonomy aligned with international benchmarks can align underlying principles and inform Asean Member States (AMS) policy makers, financial market stakeholders and international investors how to make sound sustainable financing decisions.

Chen Tao, associate professor in finance at the Nanyang Business School, said that with a unified green taxonomy, an international customer can easily identify which products are more environmentally and socially sustainable by different foreign suppliers and quickly make their purchase decisions.

“The benefits of unification [of country-level taxonomies to create a regional framework] are numerous, such as reducing the compliance cost across different countries, faster speed of adoption and greater transparency,” said Zhang Weina, associate professor in finance at the NUS Business School. Zhang is also deputy director at the SGFIN.

For example, stakeholder engagements conducted during the development of the Roadmap for Asean Sustainable Capital Markets revealed a lack of transparency of information and quality data.

Exchanges in six AMS (Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, and Vietnam) require sustainability reporting in accordance with national guidelines.

These guidelines are not standardised across countries, which make it difficult for investors to benchmark sustainability performance across companies and industries within Asean.

Prior to the roll-out of the Asean Taxonomy, “every AMS defined terms such as net-zero or carbon trading differently. If we don’t get the taxonomies consistent, we can’t set the right standards,” Agarwal said.

What are the challenges of implementing a regional taxonomy?

A key challenge in harmonising taxonomies is that some countries may wish to prioritise their own national interests.

Therefore, they may not see eye-to-eye with other member states on particular definitions in the regional taxonomy.

For example, in the case of the EU, France, which has 56 operable nuclear operators, pushed to have nuclear power included as green in the EU Taxonomy.

In exchange for support from Poland, Hungary, the Czech Republic and Slovakia on nuclear energy, the French government agreed to proactively support the inclusion of fossil gas as a transition fuel. Germany and Italy supported the inclusion of gas but opposed nuclear.

Spain opposed the inclusion of both gas and nuclear, while Austria, Denmark and Portugal opposed nuclear.

“It might be tougher to get countries across Asean to adhere to a standardised taxonomy, as Asean is an intergovernmental organisation. Regulations differ vastly across member states. On the other hand, the EU is a supranational organisation in which its member states have agreed, in certain areas, like trade, to pool their sovereignties,” said Agarwal.

“Plus, unlike the EU where member states are at a similar stage of socioeconomic development, countries in Asean could be at vastly different stages of economic development and their priorities might be even more divided,” he said.

“For example, you could get a case of Singapore pushing for coal-phase out to be included in subsequent versions of the Asean Taxonomy and coal-rich Indonesia disagreeing,” he said.

“Other challenges and drawbacks include different legal systems and cultural norms, bringing about difficulties in enforcement and green awareness,” Chen said.

Despite these challenges, experts say that the Asean Taxonomy is a step in the right direction.

The Asean Taxonomy is designed to be credible and science-based, while being inclusive and catering to the different development stages of member states.

“It may be challenging for member states to adhere to a standardised taxonomy, but it is the right thing to do if Asean is to realise its goal of economic integration,” said Agarwal.