The work of Aaron Gekoski is unlikely to be found on Netflix anytime soon.

To continue reading, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

An executive for the video streaming service recently told the British wildlife documentary maker and photojournalist that while he is a fan of his work, Netflix were looking for “cute and fluffy” content.

Gekoski’s latest project does not meet those criteria.

Eyes of the Orangutan is an exploration of Asia’s wildlife tourism industry with a special focus on orangutans, perhaps Southeast Asia’s most potent symbol of wildlife exploitation and habitat loss.

The critically-endangered great apes are being used as tourist attractions in hundreds of venues across the region, and Gekoski’s documentary examines the brutality of the trade and the ruthlessness of the people profiting from a global industry worth more than US$120 billion.

British willdlife film-maker and photojournalist Aaron Gekoski. Image: Orangutan Alliance

Gekoski documents how poachers venture into the rainforests of Malaysia and Indonesia to butcher female orangutans and take their babies, which are imprisoned in tiny enclosures and torture-trained to perform as bikini models or kick-boxers in venues around the region.

These establshments are able to justify themselves by claiming they have social value, says Gekoski. “One of the most commonly-peddled arguments for wildlife tourism is education. This claim is very deceptive.”

Gekoski observes that there is usually little more than a plaque informing visitors where orangutans come from and that they’re endangered. “People really go there to stare at an abused orangutan in a glass box,” he says.

Gekoski swapped the glamour of running a model agency in London to become a wildlife photographer more than a decade ago, and is under no illusions of the gloomy nature of the stories he tells.

If we are able to do this to one of our closest living relatives, what hope is there for any other species?

Aaron Gekoski

Fascinated with the macabre and the darker side of life, Gekoski believes that the state of the natural world should not be sugarcoated, as it has been in many popular nature documentaries.

“David Attenborough has always been my hero. When I started out as a filmmaker, I wanted to document the beauty of the natural world and share it with as many people as possible. But when I got out there, I realised that things weren’t quite as they seemed in those BBC documentaries. At every corner, wildlife is being hammered,” he says.

The exploitation of orangutans as tourist attractions is particularly disturbing because of how closely related people are to these animals, whose name means people of the forest in Malay. “If we are able to do this to one of our closest living relatives, what hope is there for any other species?” says Gekoski.

Orangutans could be extinct in the wild in a decade, if current rates of deforestation in Indonesia and Malaysia continue, so how orangutans are treated in captivity is of existential importance, he says. In this interview, Gekoski talks about the impact he hopes to have through his work, how orangutan tourism can be stopped and the difficulty in getting people to consume hard-hitting content.

Your latest project, Eyes of the Orangutan, explores the cruelty of wild-caught orangutans used as tourist attractions in Southeast Asia. What was the genesis of this project?

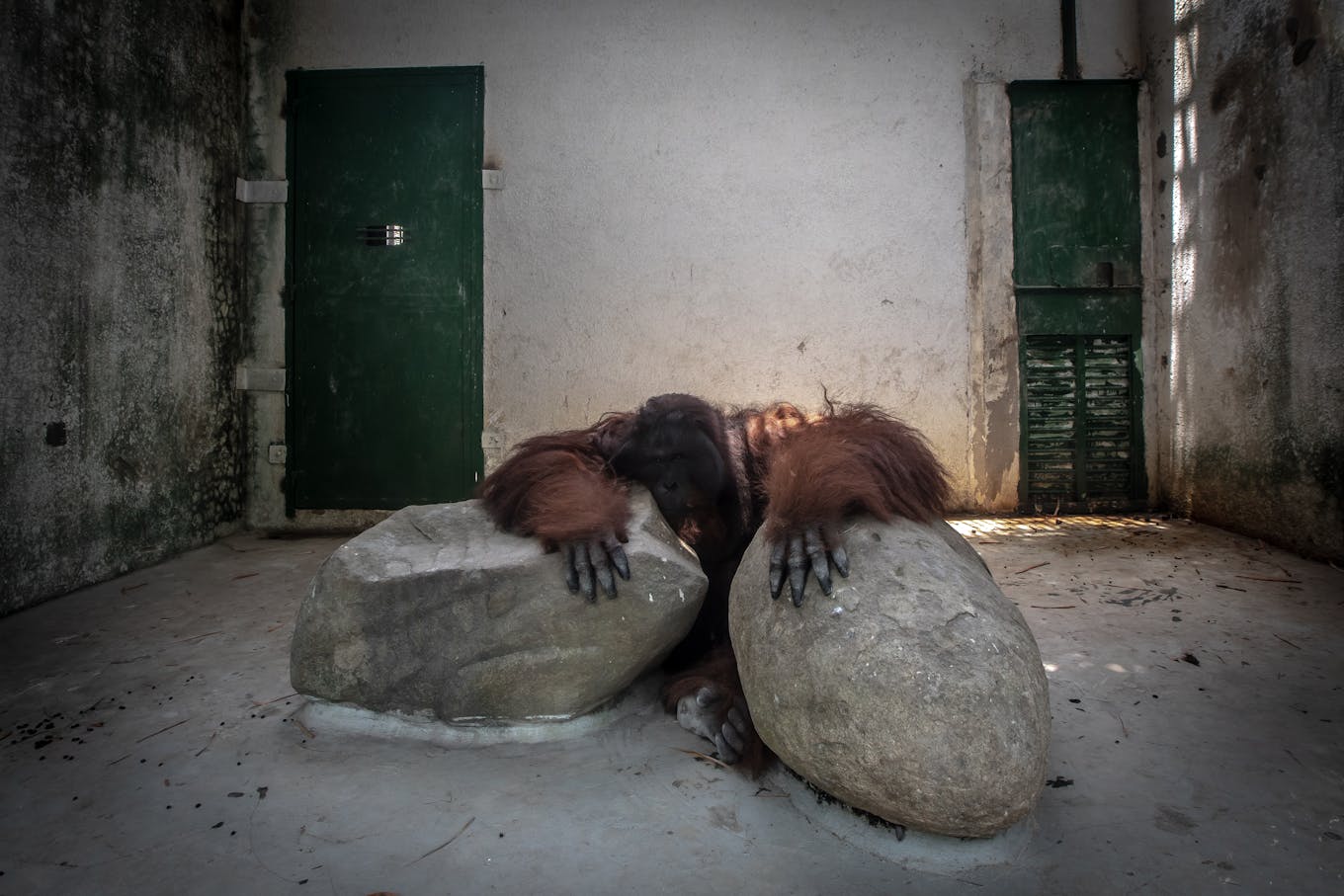

I’d been covering the wildlife tourism industry around the world for a few years. I was in Vietnam and I encountered a large, male orangutan who was being kept in a 4 metre by 4 metre glass enclosure with nothing but two concrete boulders cemented to the floor.

I spent a whole afternoon with this male, and saw how people would come by, smack on my glass and scream at him. It was a poignant scene. I could see that this male orangutan was broken. I’d filmed and photographed orangutans quite a lot before, but never in this capacity. It dawned on me that if we were able to do this to one of our closest living relatives, what hope is there for any other species? That kick-started a three-year investigation to try and get this story out there.

An orangutan hiding behind two concrete boulders in a small enclosure in Dam Sen, Vietnam. Gekoski’s encounter with this orangutan was the genesis of the Eyes of the orangutan documentary. Image: Aaron Gekoski

We traveled all over Asia, investigating the industry, and where the orangutans are coming from. We interviewed traders who explained how the babies were called from the jungle and the mother would be killed with a machete. They would steal the babies, put them in a safe-house and export them to wildlife tourism attractions around Asia.

They would be beaten, electrocuted or food-deprived to condition them to perform, for instance in boxing shows in Thailand. They would be locked away in completely inappropriate enclosures, usually without proper veterinary care or fed the right diet. Some are grossly overfed, which leads to obesity because they don’t have enough room to move around.

That would be their life for 40 or 50 years until they die. If humans were put through this, it would be called torture. I’ve done stories on the dog meat trade, which is horrific and there is a lot of suffering. But at least the animals are rounded up from the streets and are dead within 24 hours. With wildlife tourism, animals suffer years of sustained physical and emotional abuse.

On orangutan in a boxing attraction in Thailand. Image: Aaron Gekoski

How prevalent is orangutan tourism in Asia?

It’s very common in Southeast Asia. There are places where orangutans are kept all over the world, but there are more in this region, because it is a lot easier to get hold of an orangutan from the wild here.

It’s a massive problem. Almost all of the wildlife tourism attractions are completely unsuitable for orangutans. In the wild, orangutans hardly ever encounter each other except to mate. And they almost never leave the trees. Yet in the wildlife tourism attractions, you see them in very unnatural situations where they might be sprawled across a concrete floor and kept with other animals.

Orangutans are the world’s largest arboreal mammal, spending almost all of their time in trees. It is unnatural for them to be spend any time on the ground. The pictured orangutan is housed at Pata Zoo, which is located at the top of a department store in Bangkok. Image: Aaron Gekoski

Studies have shown how stressed and depressed orangutans get in captivity. You can really see it in their eyes. That’s why our documentary is called Eyes of the Orangutan.

One of the places we shot the documentary was at the Borneo Orangutan Survival Foundation in Central Kalimantan, which is doing a phenomenal job of trying to mitigate the problems orangutans face – not just tourism, but deforestation and the illegal pet trade. Jamartin Sihite, the foundation’s CEO, said of the victims of the trade: “You can see that there is nothing left behind their eyes.” That really hit home to us. Their souls have been broken.

Rescue centres like theirs are stuck in a difficult situation. People always rejoice when an orangutan is rescued from wildlife tourism centre – and in some ways they should. But after they’re rescued, what do you do with these poor orangutans? Because they have often grown up in captivity, they wouldn’t last a second if they were released into the wild. So you end up with a situation like at the Borneo Orangutan Survival Foundation, where orangutans rescued from a Thai boxing show are stuck there, and they don’t really know what to do with them.

In an ideal world, they could all be rehabilitated and released. But that’s often not realistic. It takes a huge amount of resources, land and time to rehab an orangutan to the point where it can be released into the wild – and that isn’t necessarily available. It can be done with younger ones. But with older animals, it’s often impossible.

A pair of rescued baby orangutans at the Borneo Orangutan Survival Foundation in Central Kalimantan. Young orangutans have a much better chance of being rehabilitated and released into the wild than older animals. Image: Aaron Gekoski

Why do people visit wildlife tourism centres?

People have an inherent fascination with animals. You see it in babies. The first thing they start learning is how to make animal sounds and identify different types of animals. We have an innate desire to be close to animals and inhabit their world, but that’s not usually possible. To see an orangutan in the wild is very difficult. It’s expensive and if you do see them in a truly wild situation, you might only get a glimpse of them. At a wildlife tourism attraction you can get within a metre of these animals that we have grown up learning about and being fascinated with.

Wildlife tourism is an industry that has been around since the ancient Egyptians. It is thousands of years old. And it is probably never going to go away. But with all of the knowledge we now have on animal sentience and animal intelligence, we know how much these animals suffer in captivity. We understand that animals aren’t just there to be exploited, and there’s a growing movement against wildlife tourism.

But the movement has been countered by the rise of social media. People want to have their photos taken with dressed-up orangutans and put it on social media as a reflection of themselves: ‘Look at me, I’m with a wild animal, aren’t I adventurous?’ Social media has been catastrophic for captive wildlife animals. It has really helped facilitate the wildlife tourism industry.

Orangutans dressed up at Safari World, Bangkok. Image: Aaron Gekoski

Have you become desensitised to the suffering you’ve seen?

Yes, absolutely. I think all photographers become numb to suffering and cruelty eventually. But I’ve had times where I’ve completely crashed. Just before Covid hit I’d been on one assignment after another. I’d been to 12 countries in six months, and I did a story about dog-eating in Cambodia. It pushed me over the edge, and I questioned if I could carry on.

Then Covid hit and I took some time to write a book – Animosity: Human-Animal Conflict in the 21st Century – which covers all the stories I’ve worked on over the years. It was a cathartic experience and gave me renewed vigour to return to photographing captive wildlife. It can be painful mentally, but it’s nothing compared to what a lot of animals are going through.

What impact do you hope to have through your work?

There isn’t much point in documenting wildlife tourism if there’s no change at all. But there are different measures of success. It could be just one person who sees my photos, learns about wildlife tourism and thinks twice about visiting a venue, to getting wildlife tourism establishments shut down or government legislation changed.

A boy is photographed with a boxing orangutan at Safari World, Cambodia. Image: Aaron Gegoski

How can wildlife tourism be improved?

There are various rules as to what constitutes a cruel wildlife tourism attraction and what doesn’t. First of all, any venue where you can ride or touch or take a selfie with an animal is a big no-no. All elephant riding or animal performances of any kind are a big no, because of the way the animals are trained, which is often incredibly cruel. The animals have to perform the same meaningless tricks all their lives, and are literally driven crazy.

There are many other issues to consider, such as the size of the animals’ enclosures, their diets, how well stimulated they are, and how close tourists are allowed to them. There are words bandied around to describe wildlife tourism attractions, like “eco” and “sanctuary”, which are used to fool people into visiting these places. I know highly educated people who’ve told me they visited a wildlife sanctuary in Thailand and were so happy they got to bathe the elephants. They were completely unaware of the issues surrounding the industry.

“

All you can do is educate people. But when you’re doing that, as a Westerner you have to be prepared for the fact that people will tell you to fuck off.

There are very few truly ethical wildlife tourism attractions. Wildlife tourism is a multi-billion dollar industry. There are a lot of shady characters in the industry with links to organised crime who are able to obtain animals from the wild. There were DNA studies done on the orangutans at Safari World used in the boxing shows that showed that the animals came from Malaysia and Indonesia, rather than being born and bred in Thailand, as the venue claimed they were.

The modus operandi is to capture the animals illegally, bribe government officials, fake permits and smuggle them in. The ruthlessness and brutality of the industry is hard to stomach. A poacher we spoke to said him and his friends would sit around laughing when they caught an orangutan baby from the jungle, knowing that it would end up in a boxing show.

Other orangutans, we were told, were sent off to be prostitutes. They would be shaved, made up and used for sex. You’d think this to be so unbelievable that it couldn’t be true, but it is. There was a famous case of an orangutan called Pony used as a prostitute in Indonesia.

An orangutan at Safari World in Cambodia. Image: Aaron Gekoski

How can wildlife tourism be stopped?

All countries want to avoid negative publicity. If they’re continually bombarded with negative publicity about the wildlife tourism industry, it’s going to harm the tourism industry. In Asia, shame is a powerful way to bring about change.

In the research I’ve done for stories, I’ve found that the situation in many countries in Asia has actually improved. It’s still going on, but it’s more underground. That makes it harder to document things, but it gives me hope as it means that change is afoot.

How much of a problem is being a Westerner reporting on an issue in Asia that some might not perceive to be wrong?

There can be criticism from people who say: “You know nothing about our culture, stay away.” My response is to say, “I’m a photojournalist, and I put these stories in the public domain” and try and be as factual and non-emotional as possible.

Take the dog eating story I just worked on. Who am I to tell a culture that has been eating dog meat for centuries not to do that? All I can do is explain the issues, for instance that dogs are intelligent, sensitive animals that suffer when they’re killed in this manner [dogs are drowned, strangled or stabbed before they’re sold as meat]. Also, street dogs carry diseases, and many are stolen pets.

All I can do is – and this is a very patronising thing to say – educate people. But when I’m doing that, as a Westerner I have to be prepared for the fact that a lot of the time people I will be told to fuck off. And that’s understandable.

An unreleasable orangutan at the Borneo Orangutan Survival Foundation in Central Kalimantan, Indonesia. Image: Aaron Gegoski

Have you ever confronted wildlife tourists about the cruelty they are supporting?

Yes, I have. But as much as I would like to scream and reprimand people I generally tend not to do it. Is it really going to change anyone’s perception? The most effective way to prompt people to think about what they’re doing is to ask questions. During the making of Eyes of the Orangutan, we asked a very educated couple at a wildlife tourism attraction if they knew where orangutans were from, how they thought the animals got here, and how they were trained. We could see them start to question the morality of the place.

How will you be distributing your documentary?

It is on the festival circuit at the moment. We are hoping that it will be picked up by some major broadcasters. But it is very hard to get conservation films out in the public domain. I was recently patted patronisingly on the back by a Netflix executive, who said: “You’re doing very good work out there, but we’re looking for something cute and fluffy.”

I think because people are going through difficult times at the moment, it’s particularly difficult to get conservation documentaries out there. Eyes of the Orangutan is billed as a deep-dive into a dark world of abuse. Perhaps the next wildlife trade documentary we work on we’ll frame differently.

If people see a documentary and think it’s just going to depress them, and make them feel helpless, they might not watch it. But if the documentary is an exploration of our relationship with a particular animal, that might be a more compelling way to reach people.