New research has found that China’s pledge to achieve “carbon neutrality” before 2060 is “largely consistent” with the Paris Agreement’s aim of limiting global warming to 1.5C.

But, to stay below this level of warming, the country will need to aim higher than its current net-zero goal and accomplish “deep” emission reductions in the near term, the authors state.

According to the study, to hit the 1.5C goal, the world’s largest emitter would need to cut its total carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions and energy consumption by more than 90 per cent and 39 per cent, respectively, by 2050 – compared to a “no-policy” scenario where the government has not and will not impose climate policies.

The paper, published in Science, also finds that the 1.5C mark would require China’s fossil fuel consumption to be “dramatically reduced” and demand for coal to drop to nearly zero by 2050.

Dr Hongbo Duan, the lead author, says the study “fills a gap” because no previous research had focused on assessing the efforts required by China to contribute to the 1.5C ambition of Paris.

“

China’s role in the world is now of a magnitude that makes its actions in the immediate future critical to how the world goes forward.

Dr Chunping Xie, policy fellow, Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change

China’s goal vs 1.5C limit

The Paris Agreement, which was adopted by 196 parties at COP 21 in 2015, sets the goal of limiting global warming to “well below” 2C and preferably to 1.5C above pre-industrial levels. China joined the international treaty ahead of the G20 Summit in 2016 – the same time as the US.

Last September, in a surprise move, president Xi Jinping announced that China would peak its CO2 emissions before 2030 and achieve “carbon neutrality” before 2060.

Although the 1.5C target began to receive “considerable attention” following the adoption of the Paris Agreement, only “a minority” of studies have focused on it – particularly at the country level – the paper points out. (See Carbon Brief’s in-depth Q&A about the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s special report on 1.5C published in 2018.)

The research shows that China’s goal to achieve carbon neutrality by 2060 is “largely consistent with the 1.5C warming limit” – but only if the nation carries out substantial cuts to its carbon and non-carbon emissions over the next 30 years or so.

Dr Duan, associate professor at the University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, explains the study’s key finding to Carbon Brief:

“If China keeps to the 1.5C pathways, it will be able to become carbon neutral by 2060. But if China aims for the carbon-neutral goal, it doesn’t mean that it can fulfil the emission-reduction requirements of the 1.5C goal. The 1.5C goal is tougher and stricter.”

Dr Duan and his co-authors evaluated a broad set of emissions scenarios for China using nine different integrated assessment models (IAMs) consistent with the 1.5C goal. After that, they identified the “consistent”, “model-robust” results across various outcomes.

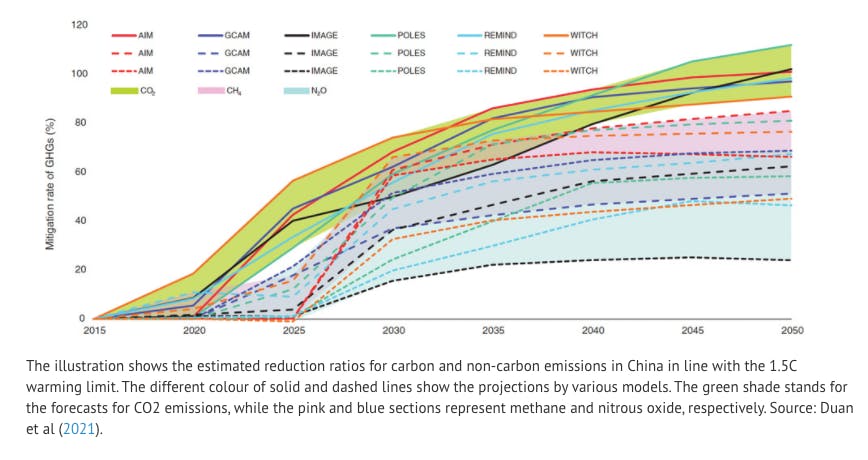

The multi-model analysis shows China would need to control both CO2 and non-CO2 emissions under the 1.5C target. The below chart, released as part of the study, highlights the projected reduction needs for carbon (green shaded area) and non-carbon emissions (pink and blue) across the participating models.

Notably, all of the modelled 1.5C scenarios include rapid CO2 reductions over the next 5-10 years whereas China has only pledged to peak its emissions before 2030.

The above calculations reveal that, compared with a “no-policy” scenario, the drop in carbon emissions would need to be between 90 per cent and 112 per cent by 2050. Meanwhile, non-carbon emissions – namely, methane and nitrous oxide – would need to dip by an average of 71 per cent and 52 per cent, respectively.

Prof Detlef van Vuuren, one of the paper’s main authors, calls China’s announced decarbonisation target “an ambitious step in the right direction”.

But he stresses that the country must reduce its carbon emissions “significantly” in the short term, as well as other reductions for non-CO2 greenhouse gases.

Prof van Vuuren holds positions at the PBL Netherlands Environmental Assessment Agency and the Copernicus Institute of Sustainable Development at Utrecht University. He tells Carbon Brief:

“Worldwide CO2 emissions need to be reduced to zero around the middle of the century. This is only possible if emissions in China are reduced significantly. Politically, China’s role is also crucial as its actions might also provide the opportunity for other countries to take steps.”

Short-term action for long-term objectives

China is the world’s largest greenhouse gas emitter producing around 30 per cent of the global total. At the same time, it is the world’s second-largest economy, undergoing rapid urbanisation and infrastructure building.

Previous analysis has called the country “an important force that heavily influences the failure or success of cooperation on climate change”.

Dr Henri Waisman, senior researcher at IDDRI’s climate programme, who was not involved in the study, says that the paper illustrates “the requirements for short-term action in order to reach demanding long-term objectives”. He explains to Carbon Brief:

“This study illustrates very well that, despite huge uncertainties at a long-term horizon, some robust outcomes can be identified for what needs to happen in the coming decade.”

Dr Waisman, also coordinator of the Deep Decarbonization Pathways Project (DDPP), says that the study shows the pursuit of the Paris Agreement goal requires “drastic” emission reduction in the coming decade with “proactive” and “strategic” action.

By examining the results of different models and establishing the “consistent” pathways across the board, the authors put forward a set of comprehensive requirements for China to stay on the 1.5C pathway.

One of the notable findings is that the warming limit calls for a “substantial decrease” in “carbon intensity” – the amount of CO2 emitted per unit of gross domestic product (GDP).

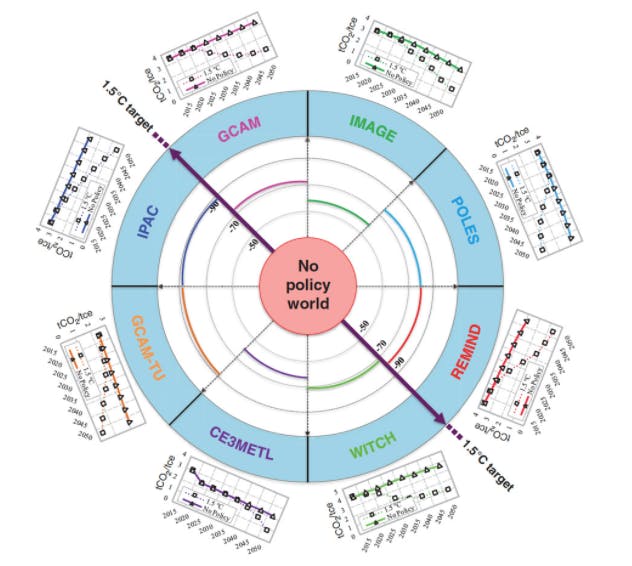

The cross-model evaluation shows that China’s “carbon intensity” in end-use energy in 2050 would need to reduce by 60 per cent to 87.1 per cent compared to a “no-policy” scenario. The below graphic from the paper depicts the required “carbon intensity” decrease levels by different models.

The overall model comparison also confirms what the authors call “the formidable role” of CCS technologies – the process of capturing carbon emissions and storing them so they are not released into the atmosphere. The paper finds that captured carbon would account for, on average, 20 per cent of total reductions in 2050.

Besides, the analysis indicates that China’s use of fossil fuels and total primary energy consumption would need to be “dramatically reduced” under the 1.5C scenario. The two indexes must be decreased by more than 73 per cent and 39 per cent by 2050, respectively, compared to a “no-policy” scenario, the paper finds.

Furthermore, the scenarios illustrate that China’s coal demand would need to decline to nearly zero around 2050 for the nation to stay under the 1.5C limit.

Dr Chunping Xie, policy fellow at the Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change, who was not involved in the study, says the most significant finding is that China’s power sector would need to cut down its emissions by 66 per cent by 2030 and achieve full decarbonisation by 2050 to be in line with the 1.5C goal. She tells Carbon Brief:

“It implies that, in the power sector, coal will need to be substantially replaced by renewables by 2030 and completely phased out by 2050. This calls into question dozens of power plants currently under construction or planned, which will either lock in decades of polluting and high emissions or have to become stranded assets, as argued in our recent paper.”

Three critical tasks under 1.5C

Through the multi-model study the research team also determined the three most critical areas in helping China to reduce its carbon emissions under the stringent temperature mark. They are, in order, energy consumption reduction, fuel switching and negative emissions technologies.

Dr Duan notes that, even though the Chinese government has demanded the nation’s total energy consumption stay under 6bn tonnes of standard coal (Gtce) between 2021 and 2030, “strict control” must be put in place. He adds that relevant policies to do this could include improvement of energy efficiency and energy saving.

According to the paper, the 1.5C goal requires a “steep decrease” in China’s fossil energy consumption. The models show that the decline could average 4.0Gtce in 2050 – 73.9 per cent lower than the “no-policy” level.

Under the 1.5C pathways, China would achieve its nationally determined contribution target for 2030 on the percentage of non-fossil energy in 2025, the study shows. Additionally, the share of non-fossil fuels in total primary energy consumption would continue to rise and could account for 30 per cent in 2030 – 5 per cent higher than the goal announced by Xi at the Climate Ambition Summit last December. The non-fossil fuel portion in 2050 is projected to be 62.8 per cent.

Dr Duan states that the second-biggest contributor is energy transition, including replacing fossil fuels with renewable energy. He adds that though CCS and negative emissions (NET) technologies might be perceived as playing “an important role”, they weigh around 20 per cent on average across all models.

The study also highlights the potential “leapfrog development” of nuclear and renewables under the 1.5C warming limit. It forecasts renewables to increase by 1.3Gtce by 2050 – 175 per cent higher than in the “no-policy” equivalent. The group of charts below represent the predicted energy restructuring across the target models.

Co-author Prof van Vuuren points out that while China is “investing heavily” in renewables already, “it is also still adding new coal capacity”. He says:

“It would be critical to bringing down the investment in coal. Similar transitions will also be necessary for other sectors, including transport (switch to electric vehicles) and buildings.”

Dr Waisman, who was not involved in the study, thinks that the role of NETs is “probably the most questionable result” of the research.

He explains that the large-scale deployment of these solutions is “highly uncertain from a technical point of view”. They could also create “important” risks of tradeoffs with other objectives, such as those linked to land-use competition, he adds.

In terms of the potential social-economic impact of climate change on China, the paper highlights the policy costs of climate governance and the social cost of carbon (SCC). The latter is a method that tries to add up all the quantifiable costs and benefits of emitting one additional tonne of CO2 and present them in monetary terms.

It indicates that various models produced “a wide range” of policy cost estimates, but, on average, the accumulated figure for China may add up to 2.8-5.7 per cent of its GDP by 2050 under the 1.5C target.

The study goes further to point out that the forecast SCCs are also highly variable, “with a cross-model difference of more than 10-fold”.

Dr Waisman says relevant actions and policy packages will need to be defined to “maximise the alignment between mitigation objectives and key socio-economic priorities”. He elaborates:

“For example, the drastic decrease of coal demand, identified as a critical condition to achieve the emission goal, raises some issues from a socio-economic perspective that will need to be considered when constructing the transition packages.”

To summarise the significance of the research in the current time, Dr Xie, who was not involved in the study, says that China must immediately adopt a mitigation pathway compatible with the 1.5C goal. She adds:

“China’s role in the world is now of a magnitude that makes its actions in the immediate future critical to how the world goes forward.”

This story was published with permission from Carbon Brief.