The story of the Amazon jungle falling victim to deforestation has now become entangled with China and its food security strategy. Brazil, a nation increasingly under fire for failing to stop the destruction of its pristine rainforest, largely exports its soy crops to China. New research shows that it is poised to overtake the United States as the largest soybean supplier to China by 2050. To keep pace with demand from the superpower nation, it has not held back from razing more trees for cropland expansion.

To continue reading, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

According to projections by researchers from the Institute of Applied Systems Analysis (IIASA), an independent global research institute, and their Chinese collaborators, China’s food demand will soon require an additional 63 million hectares of agricultural land - an area larger than the size of Spain or Madagascar - from all its trading partners, as it ramps up imports of soy, beef and dairy products.

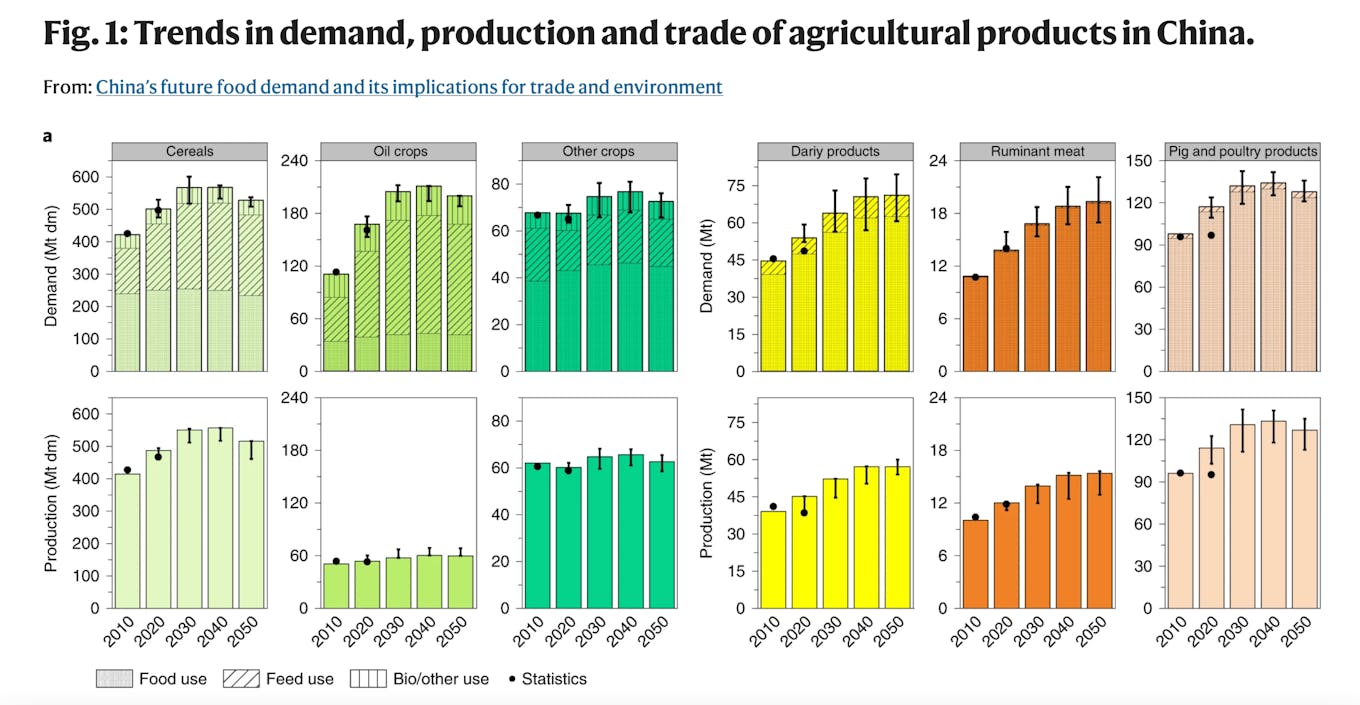

In a study published in the journal Nature Sustainability this week, the researchers project that by 2050, China’s demand for dairy products and soybeans will double from a baseline year, 2010. For pork and poultry, demand will rise by a third. The demand for cereals and other crops will increase by 25 per cent and 9 per cent respectively.

This will require China to expand its pastures and cropland by an additional 25 million hectares by 2050, said the researchers. It will also generate an additional 100 metric tonnes of carbon dioxide emissions annually.

“Assessing the impacts of future food demand requires comprehensive analyses of China’s agricultural sector,” said the study’s lead author Hao Zhao who represents the Integrated Biospheres Future (IBF) Research Group in the IIASA’s Biodiversity and Natural Resources Programme and is a researcher at Beijing’s Chinese Academy of Sciences.

The study also looks at how trade relations have to shift in order to “keep China’s rice bowl full”. “If we want to track how that impacts on the global environment, more complex models are needed because we have to look at China’s trade with other countries,” said Hao.

Soy is China’s weak link

As much as China aspires to be self-sufficient in feeding itself, it is struggling to meet its demands domestically. Long-term factors affecting its food security include a shrinking rural labour force, the reduction of available farmland by urban development and a farmland management system that is an obstacle to modern farming and large-scale cultivation. This is where trade steps in, the study finds.

For example, China’s imports of soy have been in the spotlight in recent years. China’s growing middle class has a hunger for meat and soy, a protein-rich grain, is mostly used to fatten up the hog population. China has largely relied on American soy but mounting trade tensions has made the US a less reliable supplier.

These tables show the demand and production patterns of different agricultural products in China. A portion of the crops are used for livestock feed. Image: Nature Sustainability

As China diversifies its buying and looks elsewhere for its bean, it has found Brazil to be a good substitute for America.The study projects that patterns of bilateral trade will change. China is expected to have to import 66 million tonnes of soybean from Brazil in 2050, which would account for 40 per cent of Brazil’s soybean production.

This is expected to have an adverse impact on the environment. For Brazil, already saddled with a poor track record in its protection of its forest frontier, it might mean irreversible damage. Brazil’s president, Jair Bolsonaro, known as the Amazon’s “worst enemy” by environmentalists, has been arguing that the country must prioritise economic growth, even if it comes at the cost of destroying the planet’s largest tropical rainforest.

Among China’s trade partners, Brazil also has to bear the greatest greenhouse gas emissions burden to fulfil China’s demand for beef imports, the study finds. China’s appetite for cereals and oilseeds, both water-intensive crops, will put additional pressure on the irrigation systems in the US and New Zealand.

China’s strategy: self-sufficiency and food waste curbs

“It is clear that China’s rising demand for agricultural products pose a challenge for the world. If we want to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals that have been mapped out, policies promoting sustainable consumption and production need to be further pursued in China,” said the study’s co-author Petr Havlik, who leads the IIASA’s IBF Research Group.

“We need appropriate trade agreements too. China needs to import from countries with higher resource use efficiency and at the same time be wary of resource exploitation,” said Havlik.

“

If we want to track how China’s growing food needs impact on the global environment, more complex models are needed because we have to look at its trade with other countries.

Hao Zhao, lead author of study published in Nature Sustainability

For now, China has adopted “moderate imports” as part of its official strategy on food security, focusing on ensuring that enough land resources are self-sufficient in the production of rice and wheat, two of its major staple crops.

It has also set a target to build another 66.7 million hectares of “high-standard farmland” by 2022, to be used for large-scale mechanical farming to increase crop yields per acre.

China-based agricultural analyst Zhang Xin, told Eco-Business that many countries, including Russia and Ukraine, have recently imposed strong restrictions on food exports sparking concerns about food security within China. “There is now urgency to do more to move towards a more efficient and modern farmland management system.”

With a population of 1.4 billion people, some 22 per cent of the world’s population, China is acutely aware it needs to fight on a number of fronts to keep everyone fed. In 2020, President Xi Jinping called for an end to the country’s “shocking and distressing” problem of food waste.

This quickly became a national campaign to curb food waste and several Chinese cities and provinces have since introduced new measures. Restaurants now provide smaller portions of food at higher prices and some charge diners for leaving leftovers.

For a country often obsessed with the culture of over-ordering food to create an impression for its guests, this might at least be one right step forward. “It is not going to be easy to change consumer behaviour, but it is a good effort that should be sustained,” said Zhang.