Nearly 27,000 delegates arrived in the Spanish capital in early December aiming to finalise the “rulebook” of the Paris Agreement – the operating manual needed when it takes effect in 2020 – by settling on rules for carbon markets and other forms of international cooperation under “Article 6” of the deal.

They also hoped to send a message of intent, signalling to the wider world that the UN climate process remains relevant – and that it recognises the yawning gap between current progress and global goals to limit warming.

This disconnect was highlighted by a huge protest march through the heart of the Spanish capital and by the presence of climate activist Greta Thunberg, who arrived from her transatlantic journey by sail just in time to make several high-profile appearances in the COP25 conference halls.

Ultimately, however, the talks were unable to reach consensus in many areas, pushing decisions into next year under “Rule 16” of the UN climate process. Matters including Article 6 and “common timeframes” for climate pledges were all punted into 2020, when countries are also due to raise the ambition of their efforts.

UN secretary general António Guterres said he was “disappointed” with the results of COP25 and that “the international community lost an important opportunity to show increased ambition on mitigation, adaptation & finance to tackle the climate crisis.”

The meeting was finally gavelled to a close at 1:55pm on Sunday. At nearly 44 hours after its scheduled end of 6pm on Friday, this means COP25 became the latest-ever finish by beating COP17 in Durban, which had finished at 6.22am on the Sunday.

Here, Carbon Brief provides in-depth analysis of all the key outcomes in Madrid – both inside and outside the COP…

Around the COP

This year’s COP got off to a difficult start, when Chile’s president Sebastian Piñera announced at the end of October that his country could no longer host the event. Piñera blamed “difficult circumstances”, referring to violent anti-government protests in the capital of Santiago.

With barely a month to go, Spain stepped in and agreed to take on the event in Madrid, a considerable task that the German government had said “would not have been logistically possible” at the UNFCCC’s headquarters in Bonn, where the COP was held in 2017.

Nevertheless, Chile retained the presidency, with the event rebranded as “COP25 Chile Madrid”.

Despite this last-minute venue change, the event proceeded in much the same manner as previous COPs, characterised by drawn-out debates and all-night sessions in which negotiators and then ministers discussed jargon-filled texts.

At the start of the meeting, COP25 president and Chilean environment secretary Carolina Schmidt said the conference “must change the course of climate action and ambition”. The UN secretary-general António Guterres, in the first of several interventions, asked attendees: “Do we really want to be remembered as the generation that buried its head in the sand?”

Although the world’s major emitters were never expected to announce fresh climate pledges at COP25, there was still hope that they might collectively send a strong message of intent for next year. However, talks quickly became bogged down in technical issues, such as the rules for carbon market mechanisms, which have eluded completion for years.

There was a growing sense among many attendees of a disconnect between these slow, impenetrable UN processes and the action being demanded by protesters around the world.

This was summarised by the executive director of Greenpeace Jennifer Morgan, who told assembled journalists that despite the “fresh momentum” provided by the growing global climate movement, it was yet to penetrate the “halls of power”:

“In the 25 years that I have been at every COP, I have never seen the gap bigger between the inside and the outside.”

When Greta Thunberg arrived in those halls of power, fresh from a transatlantic voyage by sail, she instantly found herself at the centre of the COP’s media circus.

At the end of the first week, the young Swedish activist joined a march through central Madrid that organisers said drew half a million people (although local police offered, without explanation, a far more modest estimate of 15,000).

In her final speech at the conference, Thunberg captured the mood when she told those assembled in the main plenary hall that the COP “seems to have turned into some kind of opportunity for countries to negotiate loopholes”. Shortly after her appearance, she was announced as Time Magazine’s “person of the year”.

Later that day, around 200 climate campaigners and indigenous rights activists – expressing frustration at the lack of progress – were ejected from the venue, following a protest outside the same plenary room where Thunberg had spoken just hours before.

A common refrain from protesters and observers was the discrepancy between the slow pace of the talks and the urgency suggested by the latest science.

The UN Environment Programme’s (UNEP) own emissions gap report, released just prior to the COP, showed the stretch 1.5C goal of the Paris Agreement is “slipping out of reach”. Even if existing climate pledges – countries’ Nationally Determined Contributions, or NDCs – are met, emissions in 2030 will be 38 per cent higher than required to meet that target, the report concluded.

This point was hammered home by a new Global Carbon Project report a few days later, which showed emissions from fossil fuels and industry are expected to continue rising in 2019 and 2020.

This apparent disconnect was highlighted further by the language used to describe the latest reports by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), the first of which covered land, and the second oceans and cryosphere.

Both of these reports were only “noted”, as opposed to “welcomed”, by the final text, though it also “expressed its appreciation and gratitude” to the scientists behind the work. (At last year’s COP24 summit, the refusal by the US, Saudi Arabia, Russia and Kuwait to language “welcoming” the IPCC 1.5C report was a source of significant tension.)

There were moves to raise ambition by some non-state actors at the COP with, for example, 177 companies pledging to cut emissions in line with the 1.5C target as part of the Climate Ambition Alliance. This came after a group of 477 investors, controlling $34tn in assets, called on world leaders to update their NDCs and step up ambition.

Finally, owing to its original location in Chile – a nation with around 4,000 miles of coastline – the leadership dubbed this year’s event the “blue COP”, laying out its intention to focus on oceans.

A report released in the first week of the COP by the High-Level Panel for a Sustainable Ocean Economy, a group of 14 heads of government, brought “a stark reminder of the serious economic consequences of our changing climate for ocean industries”.

While most attention at the COP was focused on the tense negotiations and need to send a clear signal to countries on raising their climate ambition, the president did announce in the second week that 39 countries had committed to including oceans in their future NDCs.

One of the final decision texts also requested that a “dialogue” be convened at the next meeting of the UN climate process in Bonn in June 2020 “on the ocean and climate change to consider how to strengthen mitigation and adaptation action”.

A similar dialogue in June 2020 was requested “on the relationship between land and climate change adaptation related matters”, after Brazil backed away from its objections at the last minute.

Need for ‘ambition’

From the outset, Chile made it clear this was to be an “ambition COP”, reflecting the significant gap between current pledges and what would be needed to meet global temperature goals.

The hashtag #TimeForAction was emblazoned across the conference centre and the presidency launched a “climate ambition alliance” to accelerate progress towards the Paris goals.

Guterres emphasised this in his opening address to the conference, telling parties “to step up next year”. He added: “The world’s biggest emitters need to do much more.”

Under the Paris Agreement, all parties committed to not only submitting nationally determined contributions (NDCs) for cutting emissions, but also to “[re]communicate” or “update” their pledges by the end of 2020.

Furthermore, successive NDCs must “represent a progression” and “reflect [each country’s] highest possible ambition”. Along with five-yearly “stocktakes” of progress, these regular rounds of new NDCs are at the heart of the Paris “ratchet” mechanism, designed to raise ambition over time.

However, for the majority of NDCs, which already cover the period to 2030, the Paris text does not explicitly require that new pledges be submitted next year – parties may simply “[re]communicate” the same offering they made in 2015 or 2016.

Sue Biniaz, senior fellow for climate change at the UN Foundation and a key architect of the Paris deal in her former role as a senior US negotiator, told a COP25 side event:

“The reason we threw in ‘recommunicate’ was we didn’t want it to be easy for a country to sit back quietly and maintain its target. We thought, if you had a very unambitious target, it might be more embarrassing if you had to send in a postcard saying ‘I’m sticking to my unambitious target’, than if you just had to say nothing. We’ll see next year whether that actually worked, psychologically.”

Given that current NDCs are nowhere near enough to limit warming to 1.5C, there have been efforts at successive COPs to agree text calling for greater ambition from all parties. At COP24 in December 2018, some parties tried, but ultimately failed to insert strong language on raising ambition.

With COP25 being the final summit before the clock ticks over into the deadline year of 2020, Madrid was seen by many as a last chance to secure increased ambition. Naoyuki Yamagishi, climate and energy lead for WWF Japan, told Carbon Brief that COP25 was the “last chance, the last call to make the case for raising ambition in 2020”.

UNFCCC executive secretary Patricia Espinosa reminded delegates that “ambition” was not officially on the agenda for COP25, but that many saw it as essential to send a clear message to the world. In the first week, the Chilean presidency began consultations on a series of texts, which collectively were supposed to convey this message, namely “1/CP.25”, “1/CMA.2” and “1/CMP.15”.

At the opening of the high-level political segment of the COP in week two, Teresa Ribera, Spain’s acting minister for the ecological transition, told delegates:

“Countries will have to announce more ambitious contributions in 2020 – and let me remind you that 2020 begins in exactly 20 days. This is also the year in which we have committed ourselves to announcing long-term cohesive strategies to achieve climate neutrality by 2050.”

As it stands, according to the World Resources Institute NDC tracker, just 80 countries – primarily, small and developing nations – have stated their intention to enhance their NDCs by 2020, representing just 10.5 per cent of world emissions. All the biggest emitters are absent from this list.

Although Chile postponed its plans to enhance its NDC at COP25, some promising signs did emerge over the course of the conference, most notably a fresh signal from the European Union.

On 12-13 December, EU heads of state met in Brussels and agreed to make the bloc “climate neutral” by 2050. Despite resistance from Poland, which has until next summer to come onboard, the European Commission revealed a “European Green Deal”, which, if it becomes law, will commit at least 25 per cent of the EU’s long-term budget to climate action. Ursula von der Leyen, the new European Commission president, described it as Europe’s “man on the Moon” moment.

The deal also includes a proposed timetable for boosting the EU’s NDC target for 2030, from its current aim of cutting emissions to at least 40 per cent below 1990 levels, to a higher target of “at least 50 per cent and towards 55 per cent”.

However, there was concern expressed by NGOs at COP25 that this raised pledge must be signed off well in advance of the “crucial” EU-China summit in Leipzig next September. This is because, they argue, there needs to be enough diplomatic time and, hence, leverage to use the improved NDC to persuade the world’s largest polluter to improve its own climate pledge.

To stick to this timetable, the new target must undergo a formal impact assessment by the end of the spring next year, say the NGOs. They fear that if that timing slips then there will not be enough time to use the Leipzig meeting to pressure the Chinese to up their offer. With key emitters such as the US, Australia and Brazil displaying hostility towards international climate action, a lot now hangs on China and the EU acting as one to maintain the Paris Agreement’s momentum.

Another brief moment of optimism at the COP came when the Danish parliament adopted a new climate law, setting a legally binding target to cut emissions to 70 per cent below 1990 levels by 2030.

However, a general lack of progress with negotiations led to simmering tensions in the COP25 conference centre, with the “ambition text” at the centre of the storm.

In part, this tension reflected differing interpretations of the word “ambition”. Many developed countries and vulnerable states viewed “ambition” mainly as a means to increase efforts on cutting emissions after 2020, so as to close the gap to meeting climate goals.

Others, particularly India and its partners in the “Like-Minded group of Developing Countries” (LMDCs), argued for a broader interpretation that also covered the promised provision of climate finance, as well as efforts to boost adaptation and build capacity in poorer countries.

These countries called for a particular focus on the failure of many developed countries to fulfil their climate pledges in the pre-2020 period, arguing that it was this failure that had left the world so far from meeting its aim of avoiding dangerous warming.

The splits on the “ambition” question and a range of other key debates at COP25 are shown in the table, below, with positions colour-coded as priority issues or “red lines”. The grid is based on informal intelligence gathered by Carbon Brief in Madrid, as well as public interventions by negotiating alliances during the talks. (Please get in touch with any feedback on the grid.)

Who wanted what at COP25

By the end of the second week there was a sense among some observers and parties that many richer nations were not taking the “time for action” motto seriously. Delegates from small island states and African countries were among those expressing their disappointment with the entire process.

On the final Thursday, the Association of Small Island States (AOSIS) convened a press conference in which the group’s chief negotiator Carlos Fuller said he feared having to concede on issues that “would undermine the very integrity of the Paris Agreement”:

“COP25 is demonstrating very little ambition. COP25 is a defining moment for us: it must trigger a decade of ambition. We are appalled at the state of negotiations…What’s before us is a level of compromise so profound, that it underscores a lack of ambition, seriousness about the climate emergency and the urgency of securing the fate of our islands.”

The group even called out Brazil, India and China as parties actively blocking ambitious outcomes in Article 6 discussions (see below).

As the Friday deadline for wrapping up the conference came and went, negotiators worked late into the night and on Saturday morning new texts emerged.

The response was fast and largely uniform. Though civil society observers had already described the previous round of ambition texts as weak, this new version was deemed to be even worse. NGOs representatives variously described them as “completely unacceptable”, “extremely disappointing” and “disastrous”.

Rather than strong language setting out a clear timeline for nations to enhance their NDCs in 2020, the Saturday draft 1/CMA.2 decision text relating to the Paris Agreement merely “reiterat[ed] the invitation to parties to communicate” their plans. David Waskow from the World Resources Institute said at the time: “If this text is accepted, the low-ambition coalition will have won the day.”

These sentiments were echoed in the plenary session that followed, in which nations lined up to express their disappointment with the latest offering, prompting promises from the Chilean presidency that they would reappraise and work on another round of texts.

NGOs described the language as actively undermining the Paris Agreement, which they said was based on the premise that ambition would be strengthened over time via the ratchet mechanism. Instead, Mohamed Adow, director of Power Shift Africa, said: “They are giving us a copy-paste of what was agreed four years ago.”

The final “ambition texts”, signed off at the closing plenary of COP25 on Sunday lunchtime, did manage to adopt stronger language than the widely-derided low point of the day before. (In a largely symbolic gesture, both sets of texts are titled “Chile Madrid Time for Action”.)

In particular, the agreed text of 1/CMA.2“ re-emphasises with serious concern the urgent need to address the significant gap” between current ambition and the goals of limiting warming to 1.5C or well-below 2C. In paragraph 7, the text then “urges parties to consider [that] gap” when they “[re]communicate” or “update” their NDCs, though it does not specify a fixed timeline. It also asks the UNFCCC secretariat to prepare a report adding up the NDCs ahead of COP26 next November.

Reflecting on the final “ambition text” outcome from COP25, Adow told Carbon Brief:

“I think there is a glimmer of hope that the heart of the Paris Agreement is still beating, but its pulse is very weak. Paragraph 7 in the CMA text is the lifeline which keeps alive the review and ratchet mechanism of the Paris Agreement, which is so vital for countries to enhance their climate action plans next year.”

Separate texts marked “1/CP.25” and “1/CMP.15” contain a range of other exhortations, encouragements and requests related to ambition.

In 1/CMP.15, parties are “strongly urge[d]” to ratify the Doha Amendment to the Kyoto Protocol, if they have not yet done so. This has yet to be ratified by enough parties, meaning it has not yet entered force. It contains emissions targets for developed countries, covering the years 2013-2020.

In 1/CP.25, the COP “notes with concern the state of the global climate system”. It “expresses its appreciation and gratitude” to the IPCC for its recent special reports on land and oceans, while “invit[ing] parties” to make use of this “best available science”.

The text also introduces stronger language on pre-2020 ambition, deciding to hold “round tables” at COP26 and COP27 on the implementation and ambition of pre-2020 efforts. It also asks the secretariat to produce a report by September 2022 on the basis of the round tables, with this report due to inform the “second periodic review” of progress (see below).

Article 6

Ahead of COP25, many expected a key focus to be agreeing rules for “Article 6” carbon markets and other forms of international cooperation. This is the last remaining piece of the Paris regime to be resolved, after the rest of its “rulebook” was agreed in late 2018.

By the end of the talks, Article 6 had become one of the highest profile casualties of the negotiations. With parties falling just short of reaching a deal, it will be taken up again at an intersessional meeting in June and at COP26 in November 2020.

The conversation around Article 6 is technical and full of jargon, yet the way the rules are designed could “make or break” the entire Paris Agreement, as explained in Carbon Brief’s in-depth Q&A, published a week before COP25. This high-stakes situation was a key reason for failure in Madrid.

Article 6 itself contains three separate mechanisms for “voluntary cooperation” towards climate goals, with the overarching aim of raising ambition. Two of the mechanisms are based on markets and a third is based on “non-market approaches”. The Paris Agreement’s text outlined requirements for those taking part, but left the details – the Article 6 “rulebook” – undecided.

Article 6.2 governs bilateral cooperation via “internationally traded mitigation outcomes” (so-called ITMOs), which could include emissions cuts measured in tonnes of CO2 or kilowatt hours of renewable electricity.

Article 6.4 would create a new international carbon market for the trade of emissions cuts, created by the public or private sector anywhere in the world.

Article 6.8 offers a formal framework for climate cooperation between countries, where no trade is involved, such as development aid.

Key issues within the Article 6 rulebook include:

- How to account for bilateral trade between countries via “corresponding adjustments”, ensuring only one nation claims credit for emissions cuts and that there is no “double counting”.

- Whether countries hosting carbon-cutting projects under Article 6.4 should also be obliged to carry out these “corresponding adjustments”, with a potential distinction between projects falling “inside” the scope of that country’s climate pledge versus those that are “outside”.

- How to ensure an “overall mitigation in global emissions” (OMGE), meaning a net benefit for the atmosphere, rather than emissions in one place being offset elsewhere.

- Whether OMGE should be applied to Article 6.2 as well as Article 6.4.

- Whether a “share of proceeds” from the sale of offsets should be set aside during bilateral trading under Article 6.2, or only within international carbon markets under Article 6.4.

- Whether and how to allow carbon “units” created by the Kyoto Protocol to be used within the Paris regime, potentially meeting climate goals without any additional emissions cuts.

- Whether to make specific reference in the rules to human rights.

If these rules are well-implemented, supporters argue that Article 6 could unlock higher ambition or reduce costs, while drawing in the private sector and spreading finance, technology and expertise around the world.

On the other hand, critics fear that weak rules could undermine already-insufficient ambition by allowing targets to be met on paper, even as levels of CO2 in the atmosphere continue to rise.

Before the talks began, Paul Watkinson, the outgoing chair of the “SBSTA” negotiating track, published a “reflections note”, setting out the state of play on Article 6 and other matters.

He noted that “despite a constructive mood, parties did not make progress in solving the key issues in Bonn”, at an intersessional meeting in June. The number of unresolved issues was “still high”, Watkinson wrote, adding: “Continuing in the same way would lead to failure in Madrid.”

On the opening day of the talks, one negotiator told a side event that COP25 had only a 50 per cent chance of success on Article 6, adding that while it would be a “miracle”, miracles could happen.

One meeting in the first week turned into a “rollercoaster of procedural confusion”, after parties continued arguing over how to describe negotiations initially called “get togethers” and later renamed “multilateral informal informals with co-facilitators”.

Counting progress – and lack of progress

Reflecting the scale of the challenge they faced, talks on Article 6 progressed at a painfully slow pace through the two-week summit. Crunch political fights over how to handle the issues bulleted above remained more or less open, even on the day the talks were due to close.

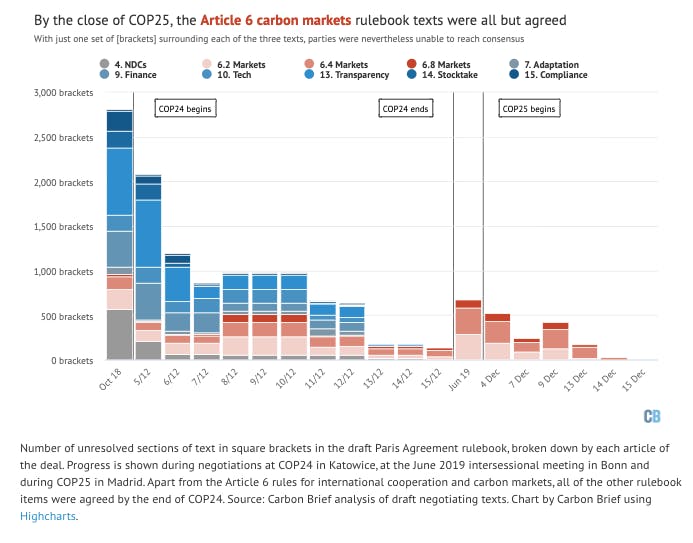

The figure below shows the number of unresolved sections of text in [square brackets], in each part of the Paris “rulebook”, across iterations of the texts at COP24 and COP25 in Madrid. The three parts of Article 6 are shown in shades of red and other parts – all of which were signed off at COP24 – are shown in shades of blue.

Starting at 672 square brackets before COP25 began, successive iterations of the Article 6 texts were released as the meeting went on. On 4 December the number of brackets dropped to 517, then fell again to 247 a few days later.

These texts, released on the middle Saturday, removed a requirement for parties to “respect, promote and consider their respective obligations on human rights”, sparking anger from indigenous groups, NGOs and many parties to the talks.

“We’re seeing what we see at the regional level: prioritisation of profits and a myopic scope on maintaining harmful institutions and power dynamics,” Janene Yazzie from the International Indian Treaty Council told Carbon Brief.

Critics say the Kyoto Protocol’s “Clean Development Mechanism” for international carbon trading has been linked with human-rights violations, as projects under it, such as large hydropower dams, can, for example, lead to people being displaced or having their livelihoods destroyed.

Therefore, they argue that safeguards must be included in Article 6, to avoid repeating the same mistakes. Yazzie says:

“The bare minimum we can do is ensure that language that respects human rights and the rights of indigenous peoples is incorporated in this final part of the rulebook.”

This wish was not fulfilled, with the agreed rules only referring to a need to address “negative social and environmental impacts”. The rules for the Article 6.4 mechanism are to be reviewed, starting in 2026 and ending by 2028, meaning the current set is locked in for nearly a decade.

On 9 December, negotiators for several of the key groups in the talks discussed the state of play at a side event held under the Chatham House rule. One lamented that the texts had gone “back to square one” and that “positions have hardened”. They said the outlook “seems bleak”.

Another negotiator identified three “crunch” issues for Article 6, namely accounting rules to prevent double counting, the transition of Kyoto activities and carbon “units”, and the “share of proceeds” that would be set aside for adaptation in the most vulnerable countries.

A third negotiator said the texts were “currently not in a state ready for ministers”, who had already started to arrive for the political phase of COP25. Another said, at least partly in jest, how “very difficult” his counterpart from another group could be during negotiations.

Throughout the event, the strength of feeling and “fundamental disagreements” between some of the central figures in the talks was palpable, with speakers referring to “very strong red lines”, the risk of “poison pills” in the text and a feeling that some were trying to impose “neocolonial” rules.

One concluded with a reference to the badges being worn by some delegates at the COP, which read “All I want for Christmas is Article 6”. The negotiator said: “Article 6 isn’t just for Christmas guys. We’ll be committed to it for the next 10 years and that’s why we need to get it right.” They added:

“Greta Thunberg has said creative accounting will not save us…I think she’s right…and there’s a lot of creative accounting still on the table. In fact, there’s some ‘no accounting’ on the table. For markets to work they need to be credible and they need public support.”

Later on the same day (Monday, 9 December), new texts were issued and the number of brackets increased to 423, with the previous iterations having gone too far in removing options favoured by some parties. The extra brackets also fixed a number of errors introduced during all-night drafting by the secretariat.

On Tuesday of week two, the Article 6 negotiations were handed from the technical talks under SBSTA to the potlicial stage of proceedings, led by the Chilean COP presidency. The presidency appointed ministers from New Zealand and Singapore, to facilitate ongoing efforts on Article 6.

By the morning of Friday, 13 December – supposedly the final day of COP25 – new versions of the Article 6 texts were released, containing some 170 brackets and all the big issues unresolved.

Nathaniel Keohane, senior vice president, climate, for US NGO the Environmental Defense Fund (EDF) told Carbon Brief this was an “astonishingly large number of brackets” at such a late stage. He said Article 6.4 was still “filled” with brackets – some 122 of them, by Carbon Brief’s count.

Kelley Kizzier, now associate vice president for international climate at EDF, was co-chair of the Article 6 negotiations at COP24. Late on Friday afternoon she told journalists:

“When the presidency called parties in on Tuesday, they referred seven issues to the ministers and let the technicians continue to work on the other issues. Not one of those seven issues has been resolved in the text.”

Much greater progress was made in texts released early on Saturday, 14 December, in which the number of outstanding brackets fell to just 31. Nevertheless, the two most intractable stumbling blocks remained unresolved in these texts, namely the Kyoto transition and double-counting.

In a sign of the high stakes in the talks, a group of progressive nations led by Costa Rica had released the “San Jose Principles” in the small hours of Saturday morning, based on a text that was initially developed at the “pre-COP” earlier this year.

The text had been circulated privately at the pre-COP, but not published in an apparent attempt to allow consensus and compromise to form.

Costa Rican environment minister Carlos Manuel Rodriguez said the principles are “a definition of success on Article 6”. They amount to red lines on the two stumbling blocks, calling for rules that would “prohibit the use of pre-2020 units, Kyoto units and allowances”, and “ensure double counting is avoided”.

Starting off with 12 countries, by the end of Saturday some 30 had signed up for these principles, including many EU member states, such as the UK and Germany.

Near-final versions of the Article 6 texts were then released in the small hours of Sunday morning, containing just one set of brackets each – in theory an indication that almost every part of the rules had been ironed out. Nevertheless, parties were unable to reach consensus, agreeing instead to return to the matter next June “on the basis of the [near-final] draft decision texts”.

Kizzier told Carbon Brief: “[This] feels a bit of a missed opportunity really. So close.”

However, former UK climate minister Claire O’Neill, who will act as COP president for COP26 in Glasgow next year, tweeted that “no deal is def[initely] better than the bad deal proposed”. She pledged to “pull no punches next year in getting clarity and certainty…work[ing] with everyone including the private sector for clear rules and transparent measurement”.

To understand why consensus was not possible at COP25, the following sections break down each of four key decision points within Article 6.

Accounting rules to avoid ‘double-counting’

Accounting rules for Article 6 were a running sore throughout the talks, as well as posing technical challenges due to the diverse nature of countries’ NDCs, which cover different timescales and may or may not cover all of the sectors and greenhouse gases in each economy.

The technical question was how to account for trade between countries with different types of NDC, given some target an emissions budget across multiple years and others aim for a particular level in a single target year. If accounted for inappropriately, then trading under Article 6.2 could have allowed countries to meet their single-year targets without actually cutting emissions.

This potential pitfall is avoided in the near-final draft, shown below, on how to make “corresponding adjustments” to avoid “double-counting”. It sets out several approaches to accounting, which parties can choose from, such as averaging the quantity of traded emissions across all years.

(The text also says that further approaches to accounting can be put forward by parties and included in the rulebook, if determined by a subsequent COP to have met its requirements.)

The political fight on double-counting centred on the application of “corresponding adjustments” to international carbon trading under Article 6.4.

Although ostensibly also a matter of good bookkeeping, Brazil, in particular, was insistent that countries hosting emissions-cutting projects under Article 6.4 ought not to be required to make a corresponding adjustment when any CO2 savings were sold overseas.

Brazil’s position was a source of confusion at and before the talks. In more than a dozen interviews focusing on Article 6, Carbon Brief received almost as many different explanations.

One source suggested even the Brazilians themselves might not understand the position, while others said that on some matters there were differences between the negotiating team, officials in Brasilia and the relatively new government ministers of far-right president Jair Bolsonaro.

Another source said that Brazil’s position stemmed largely from one man, veteran negotiator José Domingos Gonzalez Miguez, who Carbon Brief heard explaining his thinking at the COP.

He said that the heart of the matter was a different understanding of the meaning of an NDC, which was never clearly defined or agreed on. In his view, an NDC was made up of a set of government policies and programmes, rather than – as understood by others – a particular target to cut CO2.

In this case, he argued, any private sector activity resulting in Article 6.4 carbon reductions was guaranteed to be additional to the NDC – since it was, by definition, not part of the government’s own policies and programmes – and, therefore, the NDC itself should not need adjusting.

Most other parties disagree, seeing the central question in terms of the aggregate impact on the atmosphere. From this perspective, any trade in offsets must be properly accounted for. If not, then “environmental integrity” could be breached, with targets being “met” even as CO2 emissions rise.

Brazil’s firm position on the question of double-counting was reportedly a key factor in the failure to agree the Article 6 rulebook at COP24. As talks in Madrid moved into overtime, the matter was one of several outstanding issues still holding up progress.

Andrei Marcu, a former negotiator and now executive director at the European Roundtable on Climate Change and Sustainable Transition, told a briefing at the COP:

“The only real red line that is unsolvable unless someone bends is that of corresponding adjustment for 6.4, everything else is a matter of negotiation…This one is literally a defining question, I mean, there are very different interpretations of the [Paris] Agreement.”

In the relevant part of the near-final text (pdf) for Article 6.4, shown below, an initial read suggests that Brazil has been forced to give way, with corresponding adjustments being required for all trade under the mechanism, save during an “opt out period”.

However, the length of the opt-out was not fixed and would have been subject to a future decision of the COP. The text around “sectors and greenhouse gases (among others) not covered by [a host country’s] NDC” would have amounted to a double-counting loophole. The bracketed text “(among others)” is language inserted to satisfy Brazil’s unique position on the nature of NDCs, EDF’s Keohane told Carbon Brief.

Carryover of Kyoto carbon ‘units’ and projects

Almost equally contentious was the question of how to deal with billions of Kyoto-era carbon offset “units”, potentially amounting to more than five billion tonnes of CO2 equivalent.

These units were mostly generated under the Clean Development Mechanism, where projects in developing countries created “certified emissions reductions” (CERs) in the developing world.

The lion’s share of these CERs were created in a handful of countries, notably China, India and Brazil. At COP25, these countries pushed for CERs to be eligible under Article 6.4, arguing that private companies had invested in good faith and should not have their assets rendered worthless.

The EU and vulnerable countries were firmly against the transition of Kyoto units. They argued the CERs would undermine already insufficient ambition by allowing targets to be met with “emissions reductions” that have already happened, in place of additional cuts being made in the future.

Some also noted that CERs are already viewed as practically worthless on the open market, valued at around $0.2 per tonne of CO2. In addition, a supply in the billions of tonnes would far exceed demand, meaning prices under Article 6 would also be low. This would diminish the incentive for additional private-sector investment in the scheme, cutting off potential financial flows to the very countries that wanted to benefit from participation in the first place.

An additional source of Kyoto units is the “Assigned Amount Units” (AAUs) given to developed countries with targets under the protocol – effectively permits to emit a certain quantity of CO2. For some countries, weak targets or economic collapse has led to a large surplus of AAUs, often despite a lack of deliberate action to cut emissions.

One of these countries is Australia, which says it expects to hold some 411MtCO2e of AAUs that it wants to use towards its Paris target. This would amount to more than half of the effort required for the country to meet its target to cut emissions to 26-28 per cent below 2005 levels by 2030.

(No other country has explicitly said that it intends to use AAUs towards its Paris goals. Several other countries, including Russia and Poland, retain a surplus of AAUs and might be expected to try to use them in some circumstances.)

In combination, the quantity of CERs and AAUs is so large that it could significantly weaken the current level of ambition under Paris, which is already falling far short of meeting the Paris goals.

According to an analysis published during the COP by thinktank Climate Analytics: “If China and Brazil use their CERs domestically to meet their domestic NDCs, and if Australia uses its surplus AAUs towards its NDC, this would reduce global ambition by 25 per cent.”

Along with the Brazilian position on double counting, Australia’s stance on the carryover of Kyoto units faced harsh criticism at COP25. Yamide Dagnet, senior associate at US NGO the World Resources Institute (WRI), told a briefing at COP25 that Australia’s position was “outrageous” and amounted to “cheating”. She added: “That makes me angry.”

The near-final draft (pdf) of the Article 6.4 rules – shown below – would have allowed the use of CERs within the Paris regime, but with a “vintage” restriction meaning only credits created after a certain date would be allowed.

The date of this restriction was to be determined later, per paragraph 75(a), meaning that unless agreement was reached then no CERs would be allowed, according to EDF’s Keohane.

However, the draft makes no mention of AAUs, the Kyoto units that Australia hopes to use towards its Paris target. If it had been adopted, this would have left a question mark over Australia’s plans.

‘Share of proceeds’ to fund adaptation

One of the more politically fraught issues was around what “share of proceeds” from selling carbon offsets should be set aside to fund adaptation efforts in the most vulnerable countries. A further question was whether to set aside a share of proceeds under Article 6.2, as well as under 6.4, despite the Paris Agreement only explicitly mentioning the idea in the latter context.

(Dirk Forrister, president of an industry group called the International Emissions Trading Association (IETA), told a briefing during the second week at COP25 that attempts to also apply a share of proceeds to Article 6.2 was a “fight that [proponents] lost in Paris that they’ve reintroduced here”.)

Securing support for adaptation via all Article 6 trading was marked down as a key priority by negotiating blocs including the African Group, as well as the “G77 + China”. Many developed countries were resistant to the idea, seeing it as a “transaction tax” that would limit trade.

This view caused particular issues for the US delegation, which sees tax matters as untouchable in the UN climate process if it is to avoid seeking Senate approval for any resulting deal.

The EU also opposed a share of proceeds being applied to bilateral links under Article 6.2, which it hopes to use to link its emissions trading system to others. A bridging proposal emerged on the final Friday, apparently designed to avoid this objection by “encouraging” or requiring (“shall”) those participating in such links to provide adaptation funding indirectly, rather than via Article 6.2 itself.

The near-final draft (pdf) on Article 6.2 only contains the weaker, voluntary language where parties using the mechanism are “strongly encouraged” to support adaptation.

‘OMGE’ for net climate benefits

The final major area of Article 6 disagreement was around the idea of securing “overall mitigation in global emissions” (OMGE), a concept introduced in the Paris text for Article 6.4. OMGE is supposed to ensure a net-benefit for the atmosphere, rather than a zero-sum outcome where emissions in one place are offset by reductions elsewhere.

Key questions for the rulebook included how to implement a system that would guarantee OMGE and whether or not to apply a similar scheme to trading under Article 6.2.

Groups such as AOSIS argued that the only way to achieve OMGE was to automatically cancel a portion of any offsets created under Article 6. They argued that applying this cancellation to trade under Article 6.4, but not under Article 6.2, would create an imbalance that could skew the market.

Others opposed automatic cancellation under both mechanisms, arguing it amounted to a transaction tax that would limit the level of trade and impede any benefits that Article 6 could bring.

In the near-final draft text (pdf) for Article 6.2, parties are “strongly encouraged” to cancel a portion of traded offsets to support overall mitigation. In the draft for Article 6.4, at least 2 per cent of traded offsets would have been set aside for overall mitigation, with the exact figure decided later.

Loss and damage

The question of how to support countries affected by the irreversible and non-adaptable impacts of climate change has been a long-running debate at COPs over recent years.

Climate finance is in itself a contentious topic, with richer countries often falling short of the figures developing countries say they need. When finance is discussed, the conversation tends to focus on support for adaptation and cutting emissions.

But this does not capture many of the significant impacts of climate-related disasters, including extreme weather events and “slow-onset” disasters, such as sea level rise, which it may not be possible to adapt to. These phenomena disproportionately affect the world’s poorest nations.

After a year that has seen the likes of Hurricane Dorian and Cyclone Idai inflict extreme losses on vulnerable communities across the developing world, many NGO voices and parties say this issue can no longer be delayed.

At COP25, negotiators were charged with reviewing the Warsaw International Mechanism (WIM), which was established in 2013 to deal with this kind of “loss and damage”.

The WIM so far has been used to further scientific understanding of this issue, but developing countries in particular want it to reach out to those affected and do more towards one of its other goals, namely “enhancing action and support”.

Crucially, they want to secure “new and additional” money – as well as technology and capacity-building – to help deal with the irreversible damage caused by climate-induced disasters.

At a COP25 press conference called by the Alliance of Small Island States (AOSIS), Belizian environment minister Omar Figueroa laid out their position:

“Loss and damage is an existential issue for us…We need clear and predictable finance that we can access to really compensate for the loss and damage that so many of our sister nations are feeling.”

As it stood at the start of the talks, the WIM was not delivering anything “concrete” in these areas. Alpha Kaloga, a loss and damage negotiator for Guinea, told Carbon Brief there was “no clarity” on financing this area, with discussions of action and support “merely focused on instruments”.

An initial decision text for ministers to consider was released at the end of the first week and subsequently updated on Monday to incorporate input from the G77 and China group.

This group of 135 developing nations had published a document in which they made their position clear, calling for “adequate, easily accessible, scaled up, new and additional, predictable finance, technology and capacity building”.

Observers say this was already a “watered down” version of demands previously laid out by vulnerable nations, which had asked for specific “new windows” (in other words, new pots of money) in the Green Climate Fund (GCF) for loss and damage.

Over the course of the second week, parties moved towards an agreement on the creation of an “expert panel” to consider support for loss and damage and a “Santiago network” to facilitate technical support. However, Kaloga told Carbon Brief that the text for ministers was missing one vital component:

“It reflects most of our demands, but the key demand is not reflected there, which is the call for new, additional, adequate funding.”

A new text (pdf) was released on the second Friday, but pressure by rich nations led by the US meant the funding issue remained unresolved. Instead of offering “new and additional” money, the text merely “urges” developed countries to “scale up” finance.

Crucially, the only funding offer that was being considered relied on the GCF, a compromise offered by the EU.

Harjeet Singh, climate change lead at ActionAid, told Carbon Brief this would mean “eating into” finance from this already underfunded stream for other climate issues, such as adaptation.

There were also concerns that the GCF, which involves lengthy processes to access funds, would not be suitable to provide support for some aspects of loss and damage, such as immediate disaster relief.

Rather than promising new funding, vulnerable countries wanted to authorise the WIM to examine different ways of raising new money for loss and damage, for consideration at future meetings. Though there are no specific demands about how to do this, ideas being floated by some groups include levies on the fossil-fuel industry or airline passengers.

As negotiations were meant to be drawing to a close on Friday, Dr Saleemul Huq, who supports vulnerable countries in negotiations, told Carbon Brief that the need for new money was non-negotiable:

“Developing countries are adamant they are not going to bow to the US on this one. They are willing to have no decision in COP25 and take this discussion to COP26 in Glasgow, where the US is not at the table any more…Next year they will be out [of the Paris Agreement], under Trump.”

Earlier that day, Alden Meyer of the Union of Concerned Scientists, said the US delegation had informed them they would not acknowledge additional finance, “because that would push the button of a certain man in the Oval Office”.

Coming under fire for their stance, the US delegation issued a statement reminding critics that “the US government is the largest humanitarian donor in the world and we respond based on needs”.

Huq, who is also director of the International Centre for Climate Change and Development (ICCCAD), alluded to another “sticking point” with the US that had been discussed around the halls that week – the so-called “liability waiver”.

In Paris, developing nations reluctantly agreed that loss and damage could not be used to claim compensation from richer nations, with the addition of paragraph 51 of the COP21 decision accompanying the Paris Agreement.

At COP25, the US attempted to extend this waiver to the broader UNFCCC process, meaning it would also apply to parties not involved in the Paris Agreement – a group that currently only contains one nation, Syria, but which the US is set to join next November.

According to Singh, the US had initially been pushing for the WIM to only report to the CMA (and, therefore, only apply to parties in the Paris Agreement).

It then relented and said it could apply to both the CMA and the COP, but only if paragraph 51 was broadened in scope, excusing non-Paris parties from compensation.

Observers said this was a sign the US was attempting to avoid responsibility for loss and damage, even after it had left the Paris Agreement. Huq made it clear this was another clear red line for vulnerable countries.

With no more texts emerging on Saturday and tensions running high, NGOs singled out loss and damage as a key area in which the talks were failing. After the morning plenary, Singh told gathered journalists:

“Because of the bullying and blocking by the US, joined by the EU, Australia and Canada, it seems we are going to leave this COP with no support…We can’t just keep calling for ambition from developing countries without putting money on the table.”

The final decision on loss and damage that emerged was not as strong as developing nations had pushed for, with LDC chair Sonam P Wangdi commenting on the “vast disconnect” between the urgency at home and the pace of negotiations.

Even in the few hours that elapsed between different text versions early on Sunday morning some stronger language was lost, such as a specific call for “developed countries” to increase their support.

The final texts essentially note that the GCF already supports activities that can be defined as relating to “loss and damage”, with a suggestion that it – and other funds – could do more in this area in the future.

Parties also opted to fudge the issue of COP/CMA governance of the WIM, inserting a footnote saying that the talks “did not produce an outcome” and, therefore, delaying it for a future session.

With the decision delayed – but the note about delaying the decision now under the CMA text and not jointly to the COP – both sides have arrived at a compromise. However, Singh says it is still one that concerns him, noting that, in his view, suggesting the use of paragraph 51 was a “trick” to force other countries to accept the compromise of CMA governance.

Kaloga tells Carbon Brief the US did a “very good job” of ensuring the decision reflects their position. “The discussion on loss and damage has shown who has power in the world and how to exert power,” he says.

Common timeframes

One of the many matters pushed into next year was “common timeframes” for climate pledges. Ahead of the Paris COP21, countries submitted their “nationally determined contributions” (NDCs) in an ad hoc fashion, covering a range of timeframes out to 2025 or 2030.

At COP24 in 2018, parties had a “rich exchange of views”, but did agree that all NDCs should cover a “common timeframe” from 2031, with the number of years to be decided later.

The EU has a 10-year NDC to 2030 and has yet to begin the formal internal process of agreeing an update, which it has said it will deliver next year. It is said to favour deferring the decision over common timeframes until later.

Countries including Russia and Japan are reported to favour 10-year timeframes, whereas Brazil and many vulnerable countries argue for shorter terms, so that plans can be updated in light of falling technology costs and the continuing gap between collective ambition and global goals.

At a briefing held during COP25, Tosi Mpanu-Mpanu, lead negotiator for the DRC, told journalists:

“It is quite an important issue for us…We are more for NDC cycles of five years because if you go for 10-year cycles you lock in weak ambition.”

He said that pledges should be reviewed every five years in light of the latest science, with ambition ratcheted up accordingly. He added:

“When you come here you always reach for the moon and, at the end of the day, you always reach the fence, but some elements are quite fundamental and important for us.”

At a series of meetings during COP25, countries discussed an expanding list of options for common timeframes, that grew from eight to 10 and then 12 alternative formulations.

This list includes five-year timeframes, 10 years, a choice of either, or hybrids of the two. For example, countries might fix a 10-year NDC with a checkpoint half-way through, or offer a rolling pledge of “5+5” years, with firm and indicative targets. Alternatively, developed countries might be told to offer five-year pledges and developing nations a 10-year timeframe, or a choice of either.

Ultimately, agreement could not be reached in Madrid and “Rule 16” was applied. This means that the matter will automatically be taken up at the next intersessional meeting in Bonn in June 2020.

When discussions reconvence, they will start afresh rather than being based on the lengthy informal list of options under negotiation in Madrid.

Finance

While the main financial matter being discussed at this year’s COP was how to support countries affected by extreme climate impacts, the usual standing items were also being considered.

Both the Global Environment Facility (GEF) and the Green Climate Fund (GCF) guidance documents were caught up in the debate around whether to instruct them to start working more specifically on loss and damage.

There was also some discussion about the creation of a new climate finance goal, now that the deadline for “$100bn by 2020” (agreed in 2009 at the Copenhagen COP) is almost up.

Another issue being considered was long-term climate finance (LTF), a work stream that examines progress and scaling up of climate finance, but which is due to end in 2020. There is a debate about whether to continue it at all, or whether to bring it under the CMA (i.e. the Paris Agreement).

Last year in Katowice, many processes similar to LTF were replicated under the Paris Agreement, so some suggest there is no need to do the work again.

However, given that the US is expected to leave the Paris Agreement and yet is still involved in the $100bn target (which predates Paris), Joe Thwaites from the World Resources Institute told Carbon Brief there “could be a benefit to keeping the LTF agenda item where the US is still at the table”.

More broadly, as ever, finance was a major topic of discussion around the halls. Just as the talks were coming to a head on the final Saturday, African Ministerial Conference on the Environment (AMCEN) president Barbara Creecy said Africans “urgently require new, predictable and adequate financing for adaptation beyond voluntary donor assistance”.

A statement issued by BASIC ministers also criticised the lack of funding from rich nations, calling out a “lack of progress on the pre-2020 agenda”, partly “in the form of climate finance”.

Earlier in the COP, a group of 51 finance ministries known as the Coalition of Finance Ministers for Climate Action laid out their “Santiago action plan” intended to “bring considerations of climate change into the mainstream decision-making about economic and financial policies”.

Periodic review

Another contentious topic discussed in Madrid was the second “periodic review” of the long-term goal of the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), the overarching legal framework for international action to tackle warming that was first agreed in 1992. Article 2 of the Convention sets the framing for the long-term goal.

In 2010, COP16 in Cancun defined this more clearly as a long-term goal of limiting warming to 2C above pre-industrial temperatures. Following the findings of the first “periodic review”, carried out during 2013-2015, the long-term goal was subsequently updated at Paris COP21 to limiting warming to well-below 2C and pursuing efforts to stay below 1.5C.

In Madrid, negotiators initially battled over the question of whether to initiate a second periodic review at all. Having agreed to do so, they then became mired in a wider debate over how to address the failure of many developed countries to meet their pre-2020 climate pledges, dating from before the Paris Agreement was signed off in 2015.

Naoyuki Yamagishi, climate and energy lead for WWF Japan, told Carbon Brief that developed countries had wanted this to be a “science exercise”, based around the latest evidence of what it might take to keep warming within agreed limits.

On the other hand, he said that developing nations had wanted a “more active review” that also looked at developed countries’ progress towards their climate commitments, including on finance and adaptation as well as mitigation.

Ultimately, parties did agree to start a review in the “second half of 2020” and to conclude it in 2022. The agreed mandate sets out the terms of the review.

Unlike the first periodic review, the text deciding to start a second exercise explicitly says that it “will not result in an alteration or redefinition of the long-term global goal”.

The mandate also does not explicitly mention pre-2020 action, instead referring to “steps taken by Parties in order to achieve the long-term global goal”. However, the “1/CP.25” decision text creates a link back to pre-2020 action, setting up a series of “round tables” in 2020 and 2021, with a report on these events then feeding into the periodic review.

The text also says that efforts towards the long-term goal should be “assess[ed]” – a word that had caused considerable disagreement during the talks, as it was seen by some groups to imply that the review might pass judgement on countries’ efforts to date.

The text says that COP30 in 2024 will consider whether to conduct further periodic reviews of the UNFCCC’s goals or not, given that the Paris Agreement includes separate five-yearly “stocktakes”, starting in 2023, of progress towards global climate targets.

Response measures

Another strand of the talks focused on “response measures”, which is UNFCCC parlance for the effects, both positive and negative, of transitioning to low-emission societies.

This topic has been a long-running issue spearheaded by Saudi Arabia, which has pushed the idea that oil-producing nations should be compensated for the decline in oil sales resulting from decarbonisation. (Oil and gas account for around half of Saudi Arabia’s GDP.)

However, in recent years, this issue has also come to incorporate the concept of a “just transition” – helping workers in the fossil-fuel sector move into high-quality jobs elsewhere. This topic was in the spotlight at last year’s COP in Katowice, largely due to the Polish town’s long history of coal mining.

At those talks, a working group dubbed the “Katowice Committee of Experts on the Impacts of the Implementation of Response Measures” (KCI) was established to develop a six-year work plan to help countries shift to cleaner economies.

After some initial promise, the talks between 14 member nations in the KCI stalled. According to Bert De Wel, climate policy officer at the International Trade Union Confederation (ITUC), this was because of the Saudis’ close involvement with response measure, which means the issue often ends up being used as a “bargaining chip” in negotiations.

At Madrid, the talks saw Saudi Arabia and African nations go up against Europe, which they perceived as “demanding” action on this programme. While the work plan was essentially decided in the second week, De Wel says the developing nations were unwilling to agree to it and lose bargaining capital.

Against the backdrop of the riots in Chile that led to COP25 being moved to Spain, the ITUC issued a statement at the start of the second week emphasising the need for social justice to take a more central role in COPs. De Wel told Carbon Brief:

“We are very angry here. This is another example of countries not taking up human rights, workers’ rights…not even a simple work plan to discuss these aspects in the Katowice committee.”

Ultimately, amidst the dramatic final discussions about ambition, Article 6 and loss and damage, a work plan was established, albeit overshadowed by what the unions regarded as a “lack of ambition” on NDC enhancement.

Common metrics

Yet again there was no resolution, or even progress, in the long-running negotiations over “common metrics” – namely, how non-CO2 emissions (such as methane and nitrous oxide) are uniformly converted into CO2 equivalent and then reported.

Emissions metrics have become something of a totemic issue at recent COPs for Argentina, Brazil and Uruguay, collectively known as “ABU” in the talks. Farming, especially the methane-intensive rearing of cattle, is an important sector for each of their respective economies. So the precise way that methane emissions are calculated could have a profound impact on their reported national emissions, which, in turn, could affect the assessment of their NDCs. (It also has a bearing on reporting the methane emissions which leak into the atmosphere during fossil-fuel extraction.)

Under the Paris Agreement rulebook signed off in Katowice last year, all parties agreed to adopt Global Warming Potential (“GWP100″), as defined in the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) fifth assessment report (AR5), as the common metric for reporting CO2e emissions.

ABU were unsuccessful in persuading others to agree to their preferred metric, known as Global Temperature Change Potential (“GTP100”), although they did secure the option of parties being allowed to use GTP100 (or any other metric) in addition to GWP100 if they wanted to.

Put simply, under GWP100, the climate impact of every tonne of methane emitted is equivalent to 28 tonnes of CO2 over a 100-year period. Under GTP100, the same tonne of methane would only be equivalent to four tonnes of CO2. Hence, ABU’s desire that the latter metric is adopted.

The decision in Katowice now means that there is a discrepancy between the common metric used for the Paris Agreement and that used under the Convention.

Currently under the Convention, developed countries have to report(pdf) their emissions – for example, in their national communications – using the GWP100 values from the IPCC’s fourth assessment report (25 times the impact), whereas developing countries must use (pdf) the values from the second assessment report (21 times the impact), if they choose to report aggregated emissions. Many countries now want to see this all “harmonised” with the AR5 values used under the Paris Agreement for the sake of consistency, comparability and transparency.

ABU have for a while been calling for further “workshops” on the implications of AR5’s metrics methodology. Attempts to harmonise the metrics has opened a door for another attempt to keep alive ABU’s call for the use of GTP100. However, the US, for example, seem determined in Madrid to avoid anything that could call into question the use of GWP100 and a number of parties pointed out that, with the IPCC publishing its next assessment report in 2021, it would be best to wait.

To complicate matters, there are also varying views among scientists about the best way forward. Some feel that GWP100 is not necessarily the best metric for adding up emissions of long- and short-lived greenhouse gases. (For more, see a guest post by Dr Michelle Cain published by Carbon Brief last year.) Others – including the IPCC itself – have noted that the appropriate choice of metric is a value judgement that depends on its policy use.

At COP25, “Rule 16” was, ultimately, applied to the common metrics negotiations, meaning they were postponed until the intersessional in Bonn next June. But some observers do not think this has any chance of being resolved until more science on this issue is published in the IPCC AR6.

Gender action plan

A rare success story at this year’s COP was a decision on a new five-year gender action plan (GAP), intended to “support the implementation of gender-related decisions and mandates in the UNFCCC process”. The original plan, agreed at COP20 in Lima, “seeks to advance women’s full, equal and meaningful participation and promote gender-responsive climate policy and the mainstreaming of a gender perspective”.

Early negotiations did not go smoothly. Parties initially failed to deliver a text for consideration, owing in part to disagreements about the inclusion of text relating to human rights and just transition.

However, NGOs welcomed the final outcome, which they said takes into account human rights, just transition and indigeneous peoples.

Given this success, several nations led by Mexico admonished the presidency for not referencing the GAP in the decision texts released on Saturday morning. Costa Rican negotiator Felipe De Leon said it was vital for his country that this was included. The final COP decision text “welcomes” the plan.

Koronivia joint work on agriculture

While negotiators went back and forth over headline issues such as raising ambition and finishing the Paris rulebook, a little-discussed element of the COP known as the Koronivia joint work on agriculture also rumbled along.

This three-year programme will finish in Glasgow at COP26. It consists of a series of workshops examining how to conduct agriculture in a world undergoing climate change.

Previously, this strand has seen the African Group and other developing nations call for more money to support farming adaptation. In Madrid, Kenya once again raised this issue. As with other discussions around finance, developed countries have pushed back against these demands.

The talks have addressed issues ranging from finance to soils, as well as one looking at manure – or more specifically “improved nutrient use and manure management towards sustainable and resilient agricultural systems”.

Teresa Anderson, climate policy coordinator for ActionAid, says the ideal outcome would be a package of guidelines for farming under climate change: “I might call it the Glasgow guidelines on agriculture.”

However, she adds that “it’s not coming together in a very useful way so far”, with a lack of actual decisions or recommendations making their way into the final text. Everything from the Koronivia work was wrapped up in week one of the talks.

Next year, agriculture is expected to make a more central role at COP26 in Glasgow, with the potential for parties to make recommendations for climate action in agriculture.

What next?

Though some issues can now be addressed at the next Bonn intersessional meeting in June 2020, many of the key sticking points will need to be resolved in Glasgow at COP26.

All eyes now move towards the UK, where the newly elected Conservative government will be under intense international pressure to get its own climate plans in order and host a successful COP that, in essence, launches the implementation of the Paris regime. At the same time, the British government will be locked in talks with the EU over their future relationship after Brexit.

Throughout the talks in Madrid, the UK’s former climate minister and incoming COP26 president Claire O’Neill appeared at a handful of events, but was prevented from discussing next year’s conference due to UK “purdah” rules restricting civil servants from talking about political issues in the run-up to a general election.

With next year set to be an important milestone for the Paris Agreement, some delegates at COP25 were even considering how the entire COP process might need to change after Glasgow.

Describing “a time of transition for our wider UNFCCC process”, the outgoing SBSTA chair Paul Watkinson referred to a need to expand the scope of the body in his “reflections note”:

“It would be simplistic to present this as the ‘end of negotiations’ since negotiation will remain a key modality for parties to reach agreement on important issues in our future work. However, the focus and the balance of our work will evolve and implementation will take centre stage.”

Specifically, he referenced the potential for SBSTA to encompass social issues, as well as the UN’s sustainable development goals (SDGs), as well as interactions with other UN conventions covering biodiversity and desertification. The former may be particularly significant, given next year’s important “biodiversity COP” taking place in China.

US climate lawyer Sue Biniaz, a key architect of the Paris Agreement, held a session at COP25 in which she, too, speculated about the future of climate negotiations.

The outcomes of an EU-China summit in September and the US presidential election in November could both play critical roles in climate ambition, either sending a clear signal of intent to other countries or, in the case of the US, by reversing the decision to leave the Paris Agreement.

Both the G7 and G20 summits next year are set to be held by parties acknowledged as having played a disruptive role at recent COPs – the US and Saudi Arabia, respectively.

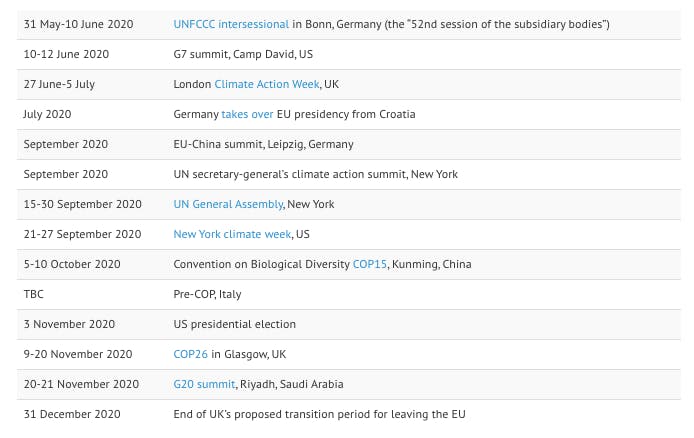

In the table below, Carbon Brief has compiled the key meetings and milestones leading up to COP26.

Laurence Tubiana, another important architect of the Paris Agreement and now chief executive of the European Climate Foundation (which funds Carbon Brief), held a session at the COP looking ahead to next year’s event and calling out governments such as Australia and Brazil that she considered to not be in line with their own people’s demands on climate.

In another appearance, Tubiana told assembled journalists:

“Governments need to be serious about what they signed up to in Paris…and deliver next year, which is a moment of truth.”

This story was published with permission from Carbon Brief.