Countries which signed the statement at last year’s climate talks to end international public financing must transfer US$28 billion from fossil fuel financing to a clean energy budget, if the world should meet its climate ambitions.

To continue reading, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

At the 26th Conference of the Parties (COP 26) in Glasgow last year, 34 countries and five public finance institutions, signed a joint commitment to end international public finance for fossil fuels by the end of 2022 and instead prioritise public finance for solar, wind, tidal, geothermal and small-scale hydro power.

Of these signatories, 18 of them were high-income countries whose annual public finance for fossil fuel projects on average between 2018 and 2020 was US$28 billion a year, while their clean energy finance was US$18 billion.

“Since signatories committed to end fossil fuel financing, we argue that they have an opportunity to shift their budget for fossil fuels into renewables that can help increase the clean energy flows to a total of US$46 billion a year,” Laurie van der Burg, co-lead of the global public finance campaign at United States-based research organisation Oil Change International, told Eco-Business.

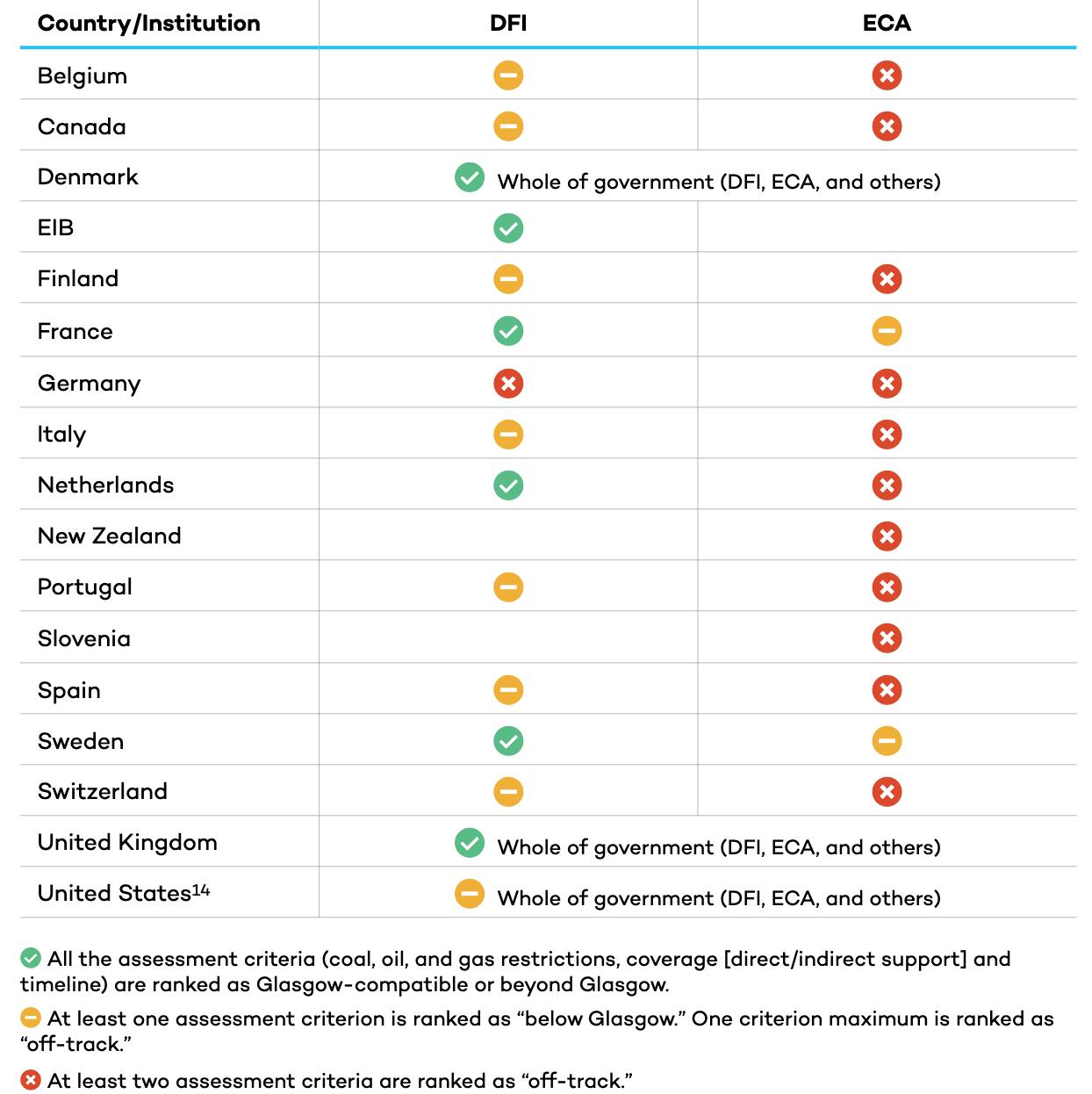

But halfway through the year, only a handful of signatories like the European Investment Bank (EIB), lending arm of the European Union, and the United Kingdom have publicly made it known that they will exclude fossil fuels in its international financing, according to a joint report by Oil Change International, Canada-headquartered think tank International Institute for Sustainable Development (IISD) and United Kingdom-based Tearfund.

Summary assessment of publicly available policies in 18 high-income signatories of the Glasgow Statement and the European Investment Bank (EIB), as of May 2022. Image: International Institute for Sustainable Development (IISD)

The US, the biggest emitter among developed nations, is part of the signatories of what is known as the Glasgow Statement, but its development financial institutions (DFIs) and export credit agencies (ECAs) have not published fossil fuel exclusion policies that match the ambition of the agreement.

International public financing institutions are composed of DFIs, otherwise called development banks, and ECAs, which offer loans, loans guarantees and insurance to help domestic companies limit the risk of selling goods and services in overseas markets. Known ECAs include Export-Import Bank of the United States and UK Export Finance.

Meanwhile, Asia’s worst polluters like China, India and Japan have yet to join the treaty. Sri Lanka is the only Asian country which signed into the pact.

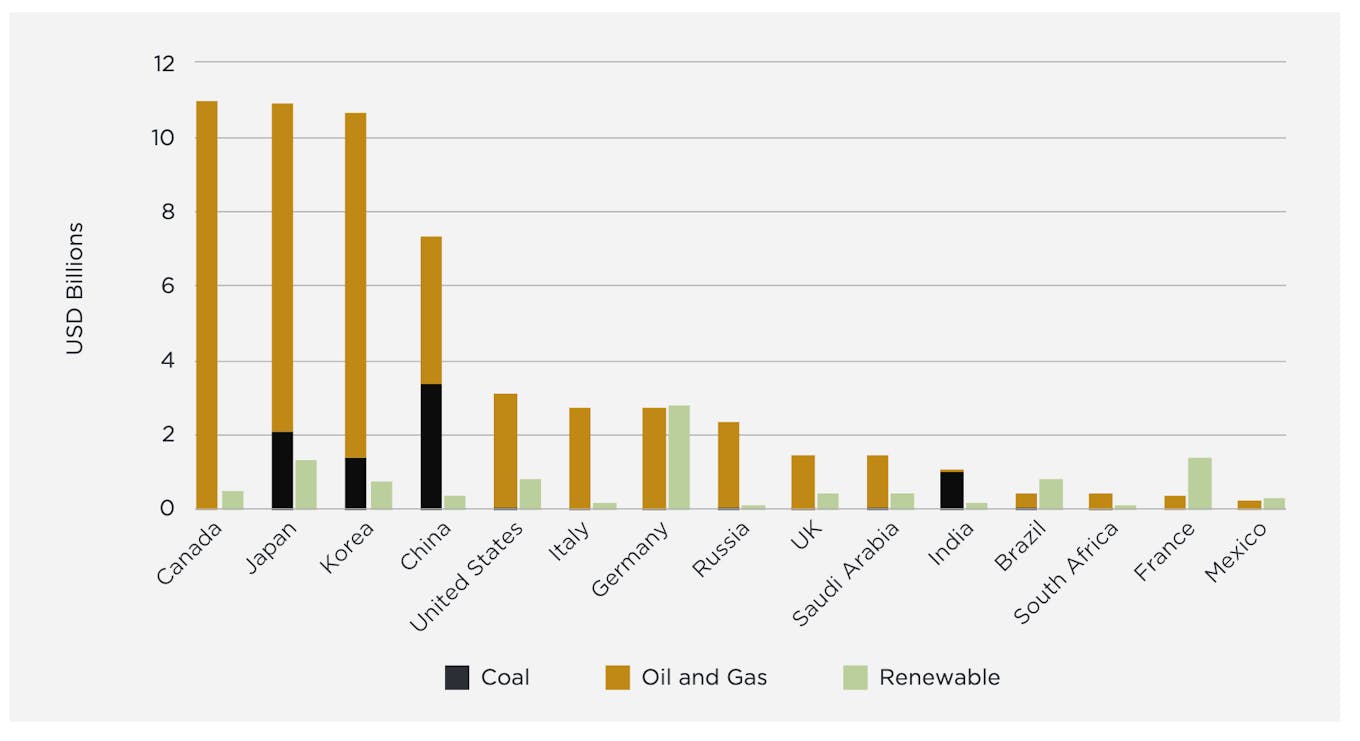

Among the signatories of the Glasgow Statement, Canada provided the most public finance to fossil fuels, with US$11 billion a year mostly for oil and gas, followed by the US at US$ 3.1 billion, Italy and Germany each at US$2.8 billion, and Spain at US$2.4 billion.

International public finance institutions have not scaled up their clean energy support, with some signatories even signaling their intention to allow continued large-scale overseas support for gas, despite their pledge.

Last month, G7 leaders, which includes the US, Germany and Italy, stated at the ministerial summit how liquified natural gas can be tapped as a “temporary response” to the oil crisis borne out of the Russian-led war in Ukraine, casting further uncertainty on the Glasgow Statement initiative.

Growing the list of signatories in Asia is “critical”

Top 15 G20 countries for international public finance for fossil fuels compared to renewable energy, annual average 2018-2020, US$ billion. Image: Oil Change International

Large financiers of fossil fuels in Asia like China and Korea have committed to ending international public finance for coal-fired power by the end of 2021 but have not yet adopted a similar pledge for oil and gas finance.

After Canada and Japan, China and Korea are among the world’s biggest energy funders at US$7.3 billion and US$10.6 billion a year respectively, which makes it “unsurprising” that it is one of the top fossil fuels funders, said van der Burg.

“For international public finance to fully shift out of fossil fuels, it is critical that countries like China, and also Korea, sign onto the Glasgow Statement,” said van der Burg.

Although Sri Lanka signed into the Glasgow treaty, this was before the energy price crisis impacted its economy, leading to the resignation of the entire administration and the subsequent resignation of its prime minister in March. As a consequence of the current crisis and without any meaningful support for cleaner alternatives, Sri Lanka may remain locked into fossil fuels, noted the report.

“It is equally critical that low- and middle-income countries join the [Glasgow] initiative so that they can help shape the donor signatories’ efforts to phase out public finance for fossil fuels and prioritise clean energy finance solutions,” the study read.