Even if more countries and corporations are allowed to partially meet their climate targets by buying carbon credits that represent emissions cuts made elsewhere, the scheme rarely benefits Indigenous people who safeguard biodiverse areas in the Asia Pacific region.

To continue reading, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

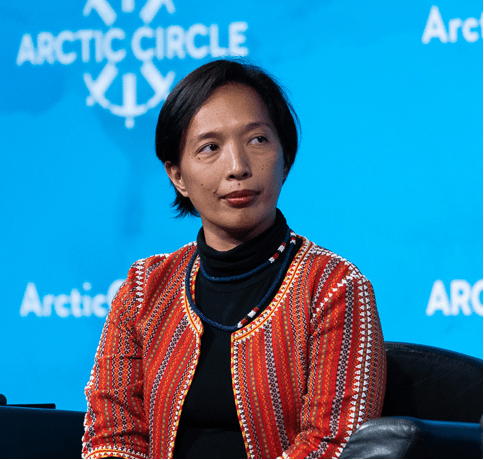

“[This is due to the] very technical and very costly procedure for Indigenous communities to prove that they are reducing emissions—a requirement of carbon traders when purchasing offsets,” said Jennifer Tauli Corpuz, director for policy of Nia Tero, a United States-based foundation that works alongside Indigenous peoples around the globe. Nia Tero is among those pushing for stronger Indigenous rights at the United Nations Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD), which is currently being negotiated in Geneva.

Jennifer Tauli Corpuz, director for policy, Nia Tero

Speaking to Eco-Business from the Swiss city, Corpuz said carbon traders who purchase offsets often require complicated formulas and expensive technology like satellite-based remote sensors, which are not accesible to Indigenous people.

Indigenous groups applying to provide carbon credits are also expected to hire consultants whose fees may reach up to US$19,000 to help them prove that they are avoiding emissions.

Corpuz, who represents the Igorot Indigenous People of Mountain Province in northern Philippines, cited how the Igorots’ Kalanguya tribe developed their own formula to measure the carbon that they sequester but the methodology did not meet the technical requirements of carbon credit buyers.

“You need to jump through so many hoops before you can prove that you are reducing this much carbon. There are no carbon trading benefits flowing to the Philippines that I know of because of these barriers,” Corpuz said.

Indigenous communities in the region also lack recognition of their rights and jurisdictions from their governments, such that the money that comes from companies that purchased offsets mays not flow into the areas where the credits where bought.

Corpuz recounted how the prime minister of Nepal announced in last year’s climate talks in Glasgow the pre-selected forests to be used for carbon trading, but the Indigenous communties living in those areas, who happened to be sitting next to her at the conference, were unaware of it.

“The government didn’t even consult them about using their forests. So there was a big fear that there might be a land grab in the places where there are a lot of trees because the Indigenous people’s jurisdiction over them was not recognised,” she said.

“Cultural burning”. Warddeken Daluk rangers in Australia help manage cultural sites and rock art with small patch burns around the sites in the cool parts of the day, to protect them from big wildfires. Image: Warddeken Land Management

However, there are Indigenous communities in the region which have been able to successfully benefit from carbon trading, like the Warddeken aboriginals in Arnhem Land in northwestern Australia, noted Corpuz.

The Warddeken tribe practices “cultural burning” where they apply culturally informed knowledge and ecologically sensitive techniques in the use of fire that can be applied to the diverse range of landscapes and ecosystems that exist in the bushfire-prone continent.

By partnering with a local university, they were able to prove how much carbon was being avoided by cultural burning practices, earning the nod of a local oil company to purchase carbon credits from them.

“One community used to be a ghost town, but because of earnings from credits, it became more populated, more schools were established and there were more jobs including for those who do the cultural burning,” said Corpuz.

Strategies for equal and direct access of funds

Indigenous leaders negotiating at the UN CBD talks are likewise lobbying for more equal and direct access of funds for communities, said Corpuz.

The Global Environment Facility, a multilateral fund that enables developing countries to invest in nature, is piloting a new financial model where money from rich countries is funneled to intermediaries like Conservation International and International Union for Conservation of Nature, which will absorb the exorbitant administrative fees meant for the recipients.

The current process does not have intermediaries which aim to shield communities from such expenses.

Another strategy to obtain financing is by working with private funding, added Corpuz.

It is a timely approach since a US$1.7 billion pledge for forests and Indigenous people was made in Glasgow along with the US$5 billion commitment of nine philanthropic organisations to protect 30 per cent of land and sea by 2030.

“The advantage is that this group of philanthropic organisations is more flexible than multi-laterals. They require simpler proposals, concept notes and financial reporting, said Corpuz. “Communities don’t have to deal with complicated reporting requirements.”