Deforestation poses a bigger problem for the climate than burning coal in Indonesia, a senior executive from the Southeast Asian country’s infrastructure investment arm said at an event on Thursday.

To continue reading, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

Harold Tjiptadjaja of Indonesia Infrastructure Finance speaking at the Asean and Asia Forum. Image: Singapore Institute of International Affairs

Speaking to Eco-Business on the sidelines of the 11th Asean and Asia Forum (AAF) in Singapore, Harold Tjiptadjaja, the managing director and chief investment officer of Indonesia Infrastructure Finance (IFF), said that 10 years ago, there was little scrutiny of the environmental impact of deforestation driven by agribusiness sectors such as palm oil industry, but the sector’s role in producing greenhouse gases linked to climate change is now a spotlight issue.

Indonesia’s biggest emitter of carbon dioxide, a major greenhouse gas, is the country’s carbon-rich peatlands, vast areas of which have been drained and burned to make way for plantations, said the boss of IIF, which was set up by Indonesia’s Ministry of Finance, World Bank and Asian Development Bank to ensure the sustainability of infrastructure development in Indonesia.

Globally, coal is the single biggest cause of anthropogenic climate change, accounting for 46 per cent of carbon dioxide emissions. But deforestation is a much bigger contributor to climate change than coal in Indonesia, Tjiptadjaja said, adding that new “more environmentally friendly” coal-fired power plants were being built as the country looked to meet rising domestic energy demand.

Emissions from deforestation and the country’s peatlands make up around two-thirds of Indonesia’s overall emissions, while the energy sector constitutes around one-fifth of the total. However, a sharp rise in overall emissions intensity in recent years has come from a surge in coal burning.

Indonesia plans to add 56 gigawatts of electricity capacity by 2027, mostly by building new coal-fired power plants. The country aims to increase coal production by 5 per cent this year, while coal exports—mainly to China—are expected to grow by 7 per cent, to 371 million metric tonnes.

While the number of coal plants under construction has halved globally since 2015, in Indonesia, the world’s fifth largest coal producer, 34,405 megawatts (MW) of coal capacity is in the pipeline, adding to 28,584 MW currently in operation.

“

Branding [technologically advanced coal plants] as a green step is complete greenwash.

Lauri Myllyvirta, senior global campaigner, coal and air pollution, Greenpeace

Green coal or greenwash

Tjiptadjaja told an audience of about 200 government and business leaders that Indonesia’s eventual decline in reliance on coal “will not be as fast” as in other Asian countries. Indonesia aims for coal to make up 30 per cent of its energy needs by 2030, and 25 per cent by 2050 as more renewable energy from solar, wind, hydro and geothermal sources is added to the mix.

New coal-fired power plants in Indonesia are being developed with “greener” technology, for example developing supercritical plants that burn less coal and produce lower emissions, Tjiptadjaja said, adding that the government also planned to develop a “more sustainable” approach to coal extraction.

He said that Indonesia is “very keen” to develop renewable energy capacity, but pointed to the Sarulla geothermal plant in North Sumatra, which finally went into operation this year after nearly 30 years in planning and development, as an example of the difficulty in developing geothermal energy.

Lauri Myllyvirta, senior global campaigner, coal and air pollution, for environmental pressure group Greenpeace, said that even with more efficient coal-fired power station technology, Indonesia’s “extremely weak” emissions regulations for coal power mean that the technology used is “completely irrelevant.”

“Branding [technologically advanced coal plants] as a green step is complete greenwash,” he told Eco-Business, adding that supercritical or ultra-supercritical plants are preferred because they are cheaper to run than lower-grade plants.

Currently, Indonesia’s regulation for sulphur dioxide (SO2) emissions from coal plants is 700 milligrams per cubic metre—20 times higher than China’s SO2 regulation for coal, Myllyvirta noted.

Earlier this year, Indonesia announced much tougher emission regulations for coal-fired power plants. The planned measures are a “step forward, but still far from best practice,” Myllyvirta said.

Indonesia’s arsenal of coal-fired power stations is responsible for an estimated 7,100 premature deaths every year, a number that will rise to 28,000 a year once planned coal plants are built, according to estimates made by Greenpeace and Harvard University.

The fires are back

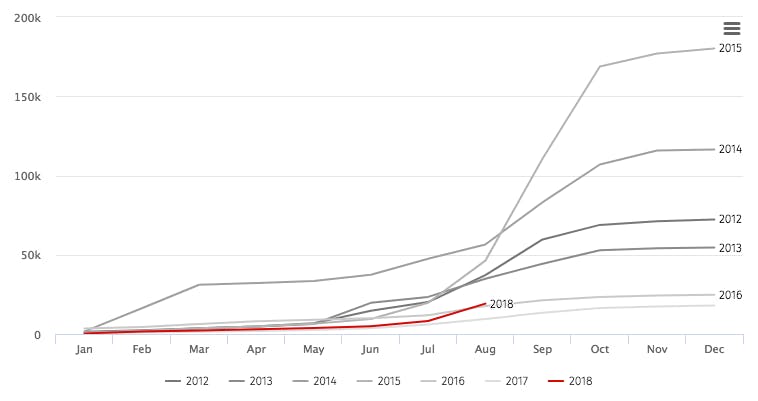

Though 2016 and 2017 were relatively fire-free, 2018 has seen a marked increase in fires over the last month as dry conditions returned to the archipelago. Nearly three times as many hotspots have been identified so far this year than in all of 2017, according to data from Greenpeace. In 2015, the year of the worst ever haze in Southeast Asia, emissions from Indonesia’s burning peatlands exceeded the emissions of the entire US economy and caused a regional public health crisis.

Fire hotspots in Indonesia 2012-2018

Fire season progression. There has been a marked increase in fire hotspots between July and August. Source: globalforestwatch.org

Indonesia’s Meteorology, Climatology and Geophysics Agency has warned that the increasingly dry weather could see the number of peatland fires increase through September.

Last week, a Palangkaraya High Court found Indonesia’s president Joko Widodo guilty of negligence in the government’s handling of the 2015 peatland fires. The fires, which consumed 261,000 hectares of forest and peatland, were responsible for about 100,000 deaths from smoke inhalation, according to a study by Harvard and Columbia universities. Indonesia dismissed the findings, claiming that 24 people died as a result of the fires.