As Southeast Asia emerges from the Covid-19 pandemic, it faces yet another deadly disease – dengue fever.

To continue reading, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

Dengue fever is a tropical disease usually spread by female Aedes aegypti mosquitoes. Symptoms, which typically begin three to fourteen days after infection, can include a high fever, headaches, rashes and joint pain. In severe cases, shock, internal bleeding and even death can occur in sufferers of a condition also known as “breakbone fever”.

This year, the number of dengue cases in Ho Chi Minh City has risen by a third, with a 500 per cent spike in severe cases. In neighbouring Cambodia, the total number of cases has increased by a whopping 87 per cent. Developed nations have not been spared either, as Singapore recorded 15,580 cases in the past six months alone, three times the number for the whole of 2021.

Dengue is endemic to Southeast Asia as the region’s warm and humid climate makes it a hotspot for mosquito-borne illnesses. During the monsoon season (mid-May to early November), dengue infections are expected to rise with heavier rainfall. However, the unusual rise in infections this year has left health authorities scrambling for answers.

What is a neglected tropical disease?

Dengue is categorised as a neglected tropical disease (NTD). An NTD is a tropical disease which can cause serious illness, disability and disfigurement, but does not receive as much publicity or funding as more well-known diseases like HIV/AIDs, malaria and tubercolosis.

“It is difficult to generalise reasons for the surge. There are lots of local nuances, and the principal driver of dengue in Singapore might not necessarily be the same as in Kuala Lumpur or Jakarta,” explained Professor Ooi Eng Tong, deputy director of the Programme in Emerging Infectious Diseases at Singapore’s Duke-NUS Medical School.

Besides the astronomical number of cases observed this year, scientists are worried about dengue’s overall upward trend. Between 2015 to 2020, the number of cases in Southeast Asia has risen by almost 50 per cent, said Dr Laith Yakob, an infectious disease ecologist at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine.

“

Warmer temperatures actually change mosquito behaviour. They bite more frequently when it is warmer.

Dr Laith Yakob, associate professor, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine

During the height of the pandemic, there was a slight lull in cases. Current research suggests that this drop could be due to the lack of human traffic in schools and public areas, which are usually dengue transmission hotspots. However, as the region reopens, transmission rates have surged back up.

In Singapore, the rise of previously uncommon strains of dengue could be another key reason for the dengue outbreak.

Globally, there are four strains of dengue viruses: DENV-1, 2, 3 and 4. DENV-2 used to be the most common strain in Singapore. So when the island nation was hit with DENV-3, cases increased in frequency and severity as there was little immunity against the strain.

“Two years ago, the 2020 dengue outbreak in Singapore was caused by the DENV-3 strain. In the years between 1992 – 2020, and now, DENV-3 has been present, but for some reason we don’t quite understand, it was never prevalent,” Ooi said.

Urban hotspots

An inspector checking for mosquito larvae in pots in Southern Vietnam. Image: Wikimedia Commons

Could climate change be playing a role in the surge in dengue cases as well? Researchers say attributing year-to-year fluctuations to climate impacts can be difficult. However, a growing body of scientific evidence from China and Vietnam has established strong links between extreme weather and dengue outbreaks.

“Warmer temperatures actually change mosquito behaviour. They bite more frequently when it is warmer, thereby infecting more people,” explained Dr Laith Yakob.

Indeed, Southeast Asia has experienced especially warm and rainy weather this year. Temperatures in Singapore have reached 36.7°C this May, the highest for that month on record. High temperatures and humidity also favour mosquito survival, further increasing the likelihood of transmission.

The region’s growing urban density could be another reason for dengue’s upswing. Southeast Asia’s urban population is expected to increase by 100 million by 2030. Shifting weather patterns will likely exacerbate this trend, as rural agricultural workers are increasingly pressured to move to cities for better economic opportunities. As dengue fever is transmitted to humans via an infected mosquito’s bite, cases are expected to increase as larger congregations of humans means more hosts for the disease.

Moreover, urbanised areas provide a larger range of aquatic habitats for mosquitoes to lay their eggs in. Aedes aegypti, the foremost spreader of dengue, can easily live close to humans and breed in common domestic water receptacles like flowerpots and even toilet bowls.

Fighting dengue

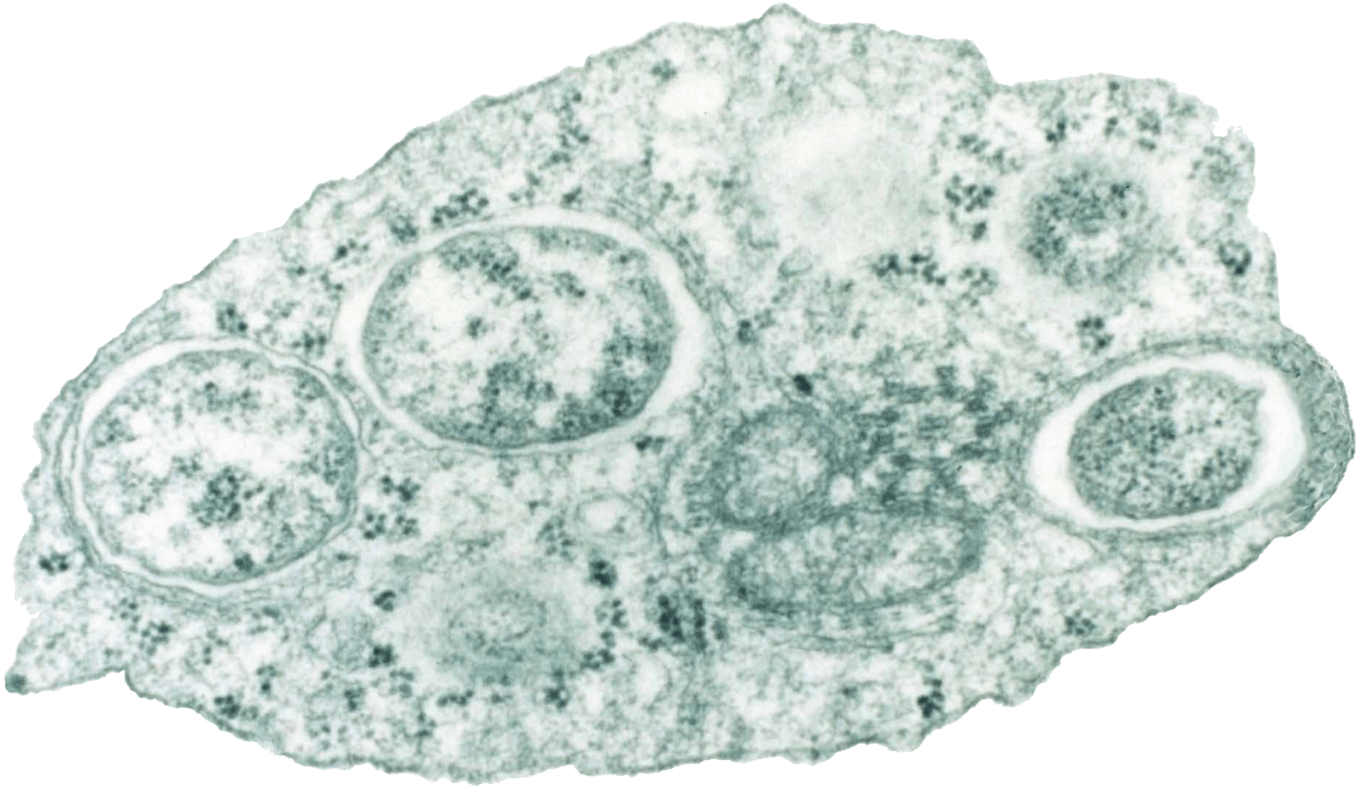

Transmission electron micrograph of Wolbachia within an insect cell. Image: Wikimedia Commons

Fortunately, scientists are working on novel technologies to stop the spread of dengue. For instance, Singapore has recently expanded its trial to release non-biting male mosquitoes carrying the Wolbachia bacteria into some of its housing estates. Female mosquitoes carrying the Wolbachia bacteria produce eggs that do not hatch. The scheme seems to be working, as estates already participating in the scheme have seen dengue cases drop by up to 88 per cent. Several new vaccines are currently under development as well, such as Japanese pharmaceutical firm Takeda’s TAK-003.

Nevertheless, experts warn the disease should not be taken lightly, and that solutions must be holistic. As it stands today, dengue results in more than 36,000 deaths a year, and statistical models predict 2.25 billion more people will be at risk of dengue by 2080.

“If dengue is not properly managed, its fatality rate will exceed that of Covid-19,” cautioned Ooi. “The illness is actually very debilitating for the patient. I’ve heard patients say that even if it doesn’t kill you, you wish it had. At the end of the day, there is no silver bullet that can solve dengue.”