Action to reduce greenhouse gas emissions to stave off the most catastrophic consequences of climate change continues to lag far behind what is needed — in practically all countries and sectors — according to a new report from Climate Action Tracker (CAT).

To continue reading, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

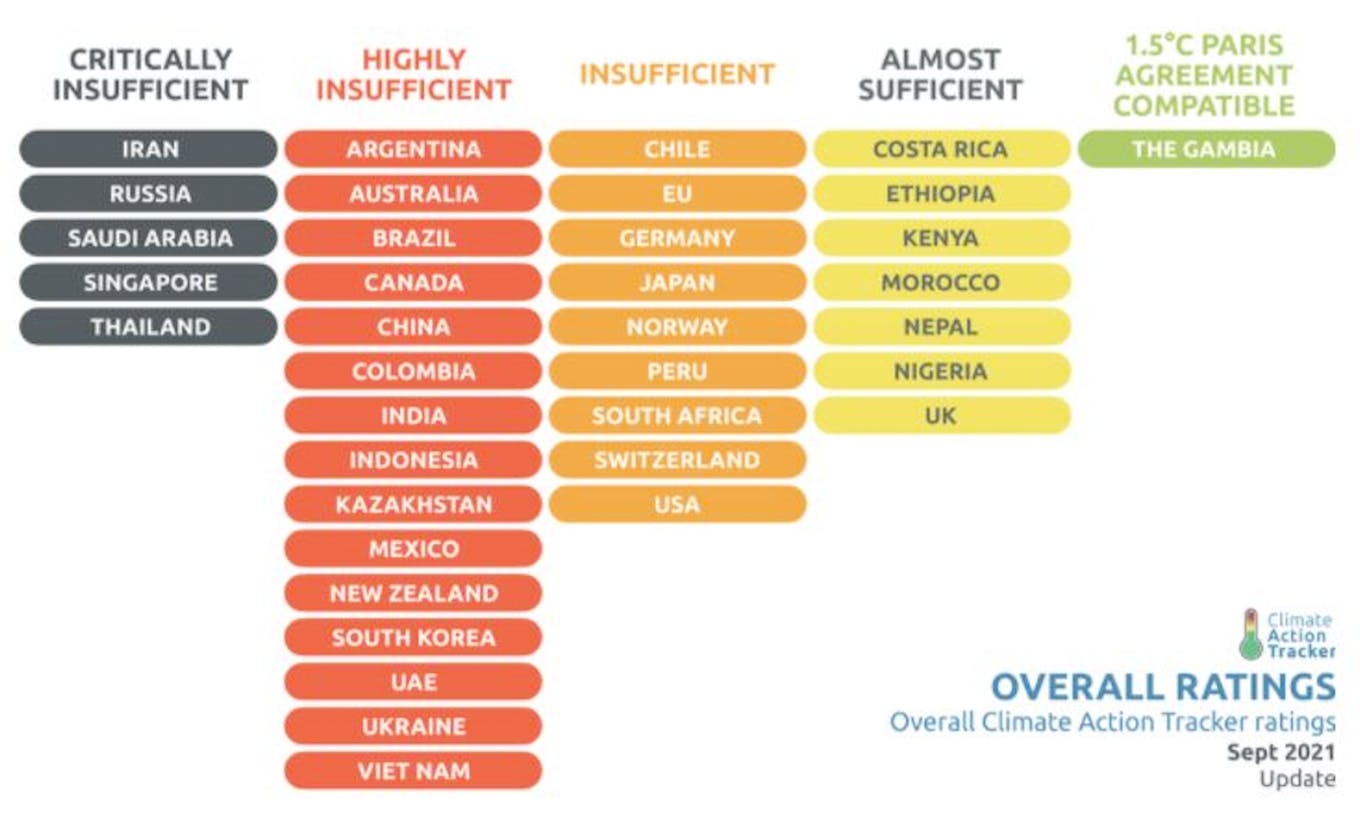

With critical COP26 United Nations climate change negotiations just two months away, and one month after a sobering report on climate change issued a “code red for humanity”, only one country — the small West African nation of Gambia — is deemed to be taking sufficient climate action in line with a 1.5°C rise in global temperatures, the warming limit that world leaders pledged in 2015 they would not exceed by dramatically reining in emissions.

Under the Paris Agreement six years ago, 195 countries agreed to a goal of limiting global warming to “well below” 2°C and to “pursue efforts” towards 1.5°C, with each government committing to do what it could to put the world on track to curb climate change.

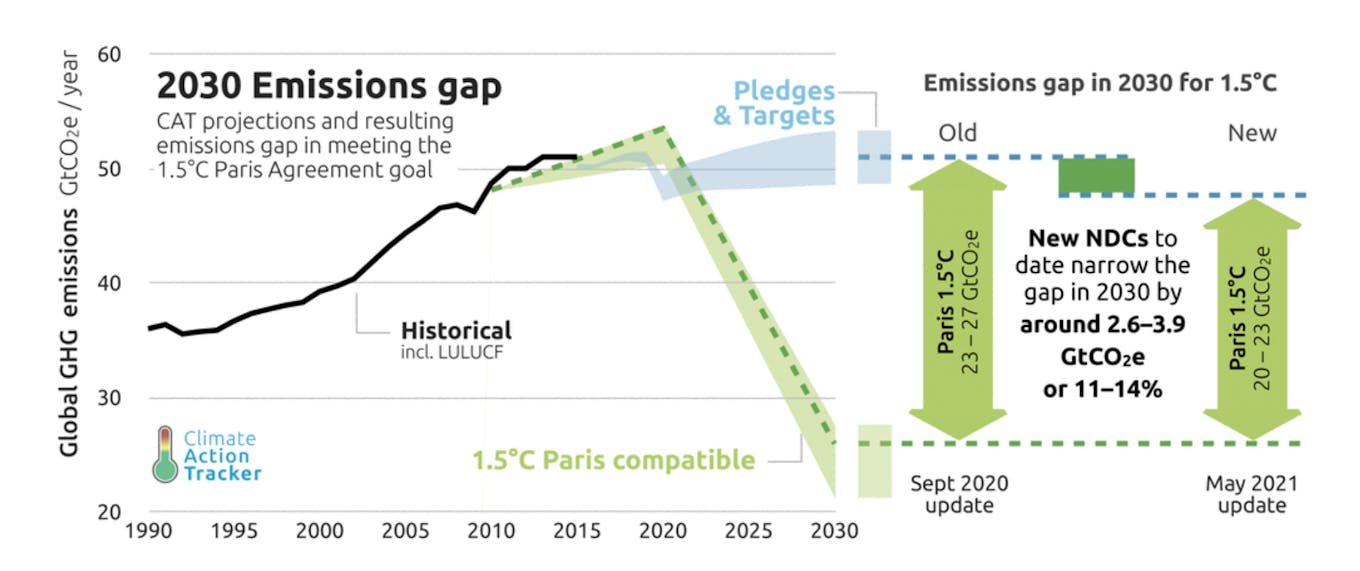

But over the past year, countries have narrowed the gap towards what is needed for 1.5°C by a mere four gigatonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent (GtCO2e), or up to 15 per cent, CAT’s data shows. Most countries with strong targets are not on track to meet them, while more have failed to bring forward stronger commitments for 2030, a critical year for carbon reductions.

Of most concern are governments that have submitted the same or less ambitious 2030 carbon reduction targets, known as nationally determined contributions (NDCs), than they had put forward in 2015. These countries are Australia, Brazil, Indonesia, Mexico, New Zealand, Russia, Singapore, Switzerland and Vietnam.

The least ambitious countries for climate action are the major oil and gas hubs of Iran, Russia, Saudi Arabia and Singapore. Thailand is also among this group classed as “critically insufficient” for climate action.

How countries are faring on climate action, September 2021. Source: Climate Action Tracker

Only one industrialised country, the United Kingdom, has a domestic target rated as 1.5°C compatible. The UK, where industrialisation began in the 1700s, enshrined a climate target of achieving net-zero emissions by 2050 into law in 2019.

Germany and Norway are rated as close to 1.5°C compatibility. However, CAT also assesses countries according to their contribution to international climate finance, and most developed countries, which have pledged to give poorer countries US$100 billion a year in climate change adaptation and mitigration loans under the Paris Agreement, have failed to give anywhere near that level of support.

The report notes that the most important target date for carbon reduction is 2030, by which time global emissions must be cut by a half. The authors estimate that with the level of current action, global emissions will be at roughly today’s level in 2030, when the world will be emitting twice as much as required for the 1.5°C warming cap.

The 2030 emissions gap. Source: Climate Action Tracker, September 2021

Over the past 18 months, a large number of countries, including China, Korea and Japan, have declared net-zero targets, which the report says “give reasons for hope, but will fail without sufficient 2030 reductions.”

There needs to be stronger alignment between 2030 targets and net zero goals, argued CAT. “Our assessment shows that most net zero targets are formulated vaguely and do not yet conform with good practice,” the report said.

Robust short-term targets and pathways towards achieving net-zero targets are needed for greater credibility. If fully implemented, the national net-zero targets currently in play could cut global warming to 2°C, the report predicts.

However, even 1.5 degrees warming is projected to be catastrophic. Scientists predict that nearly one billion people could swelter in more frequent heat waves, hundreds of millions may struggle for water because of droughts, and biodiversity could severely dwindle.

“Much more warming than that, and life on our planet will become increasingly unrecognisable,” United States climate envoy John Kerry warned in July. “There is still time to put a safer 1.5°C future back within reach — but only if every major economy commits to meaningful (emissions) reductions by 2030,” he said.