The research, published in Nature Food, examines the land use, water use and greenhouse gas emissions associated with growing four staple crops: rice, wheat, maize and potatoes. It finds that a large-scale dietary shift towards potatoes, combined with better growing methods, could reduce the greenhouse gas emissions of these staples by up to 25 per cent.

In addition to the emissions reductions, the researchers find that integrating more potatoes into the diet would cut the total land used for staple-crop agriculture by about 17 per cent by 2030 – even when accounting for the country’s growing calorific need.

However, the authors note that it remains to be seen whether such a major dietary shift can be carried out on a large scale. And, they warn, if the higher potato production isn’t matched by domestic demand, the climate benefits will be offset by the need for rice imports from neighbouring countries.

‘Potato’s comparative advantage’

In 2015, the Chinese government implemented a national strategy known as the “Potato as Staple Food” policy. Its stated aim is to improve food security – the country’s ability to feed its own population without reliance on imports – by increasing both production and consumption of potatoes across China.

Among other targets, the strategy called for 30 per cent of potatoes to be consumed as staples by 2020. While the tuber serves as a staple in some areas of China, in most parts of the country, it is used as an ingredient for meaty or vegetarian dishes that are eaten alongside a staple.

Potatoes have several agronomic benefits over other staple crops. They are more drought-resistant and more geographically adaptable, making them more resistant to a changing climate. Potatoes also contain higher levels of certain micronutrients, such as potassium and vitamin C, than rice, wheat and maize.

Although China is a major supplier of staple crops – producing around one-quarter of the world’s rice, maize and potatoes and nearly one-fifth of its wheat – potatoes only take up 6 per cent of the nearly 1m square kilometres of cropland devoted to staple crops in the country.

Worldwide, the production, processing, transport and consumption of food are responsible for about one-third of human-driven greenhouse gas emissions. But discussion of lowering agriculture’s impact generally only focuses on reducing consumption of beef, dairy and other red meats.

This focus on meat can miss out on other areas where change could help reduce emissions, says Prof Laura Scherer, an industrial ecologist and environmental scientist at Leiden University who was not involved in the study. (Scherer wrote a commentary piece that accompanied the paper.) Scherer tells Carbon Brief:

“[Staples] are not really the foods with the highest impact intensities, but because we consume such vast amounts of staples, that change can still make a significant contribution.”

And since the Chinese policy is focused on food security and nutrition, there has been less interest in analysing the environmental impacts of such a large-scale dietary shift, Prof Yi Yang, an industrial ecologist at Chongqing University, says. Yang, who is one of the authors of the new study, tells Carbon Brief:

“Very little research has been done on ‘what’s the environmental implications of this policy?’ And why it might matter is that different crops have different environmental footprints. That’s very clear to those of us who have studied agricultural systems, but not necessarily clear to the policymakers.”

When Yang and his colleagues analysed the environmental impact of each of the four staples, they found that potatoes have a lower impact in several ways. Compared to rice, maize and wheat, potatoes emit significantly lower amounts of greenhouse gases on a per-calorie basis. Potatoes also used less water than each of the other staples and required less land than maize or wheat.

The chart below shows the total land use, greenhouse gas emissions and water use for each of the four staple crops studied – from rice in the left-hand maps through to potatoes on the right – as well as the intensity of land use, emissions and water use (defined as the use or emissions on a per-calorie basis). The darker shading indicates higher totals and intensities across China’s provinces.

The paper considers three main contributors to greenhouse gas emissions in staple crop agriculture: crop planting, fertiliser application and production and transportation.

Virtually all of the greenhouse gas emissions from staple-crop planting in China come in the form of methane emitted as a result of rice farming – more than 150m tonnes of CO2e (MtCO2e) in 2015.

Fertiliser application, which has increased in China by over 300 per cent over the last three decades, is another major source of agricultural emissions in the form of nitrous oxide. Nearly half of the 128MtCO2e attributed to fertilisers is due to maize farming.

Lastly, potatoes only account for 4.5 per cent of the 267MtCO2e emitted from the agricultural production and transportation sectors. This, the researchers note, is “relatively smaller than its share of cultivated land” because potato farming does not require as much diesel and electricity as farming other staples.

Taken together, the authors write, these figures demonstrate “potato’s comparative advantage” among staple crops in lowering greenhouse gas emissions.

‘Room for improvement’

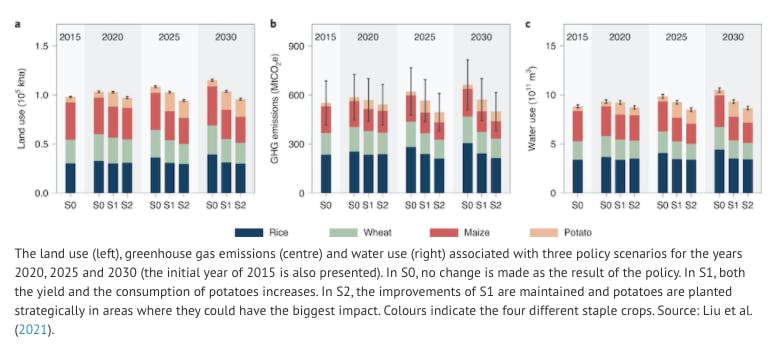

In order to evaluate the potential effects of the policy, the researchers examined three scenarios using models of crop demand, yield growth and land use. Each scenario built on the previous one and included the projected increase in calorific demand for staple crops (expected to rise by over one-third in China by 2030).

The first scenario (“S0”) assumes no dietary or production changes. The researchers determined that in order to meet the calorific demand, the amount of land used for farming would have to increase by about 17 per cent. Furthermore, they found, the greenhouse gas emissions and water usage associated with staple crop agriculture would each increase by about 20 per cent by 2030.

Under the second scenario (S1) Potato-as-Staple-Food strategies to improve potato production were accounted for. These include the adoption of high-yield potato varieties and increasing the relative proportion of calories sourced from potatoes.

They project increasing potato yields by 125 per cent and using potatoes to meet the gap between yield and demand of the other staples. This, the authors find, would result in a 14 per cent reduction in greenhouse gas emissions, a 10 per cent reduction in total land cultivation, an 11 per cent reduction in water use and a 10 per cent increase in the mean calorific yield of the staples by 2030.

For the final scenario (S2) a “strategic siting” plan was enacted on top of the other policies. This linear-regression model reallocates the crops to minimise greenhouse gas emissions while making “only slight adjustment[s]” to the planting areas of the other staples.

Taken in combination with the other changes, S2 results in a 25 per cent reduction in emissions, a 17 per cent reduction in land use, a 17 per cent reduction in water use and a 19 per cent increase in calorific yield.

The chart below shows the projected land use (left), emissions (middle) and water use (right) for each of the three scenarios. The bars in each figure are broken down to show the relative contributions of rice (blue), wheat (green), maize (red) and potatoes (orange).

One key to successfully implementing the policy will be closing the “yield gap” with other countries, Yang tells Carbon Brief. The average yield of potatoes in China was 15 per cent below the world average in 2015 and 65 per cent below that of “high-yield” countries such as the US, New Zealand and Belgium.

One key to successfully implementing the policy will be closing the “yield gap” with other countries, Yang tells Carbon Brief. The average yield of potatoes in China was 15 per cent below the world average in 2015 and 65 per cent below that of “high-yield” countries such as the US, New Zealand and Belgium. Potato yields in China lag behind these high-yield countries for several reasons, Dr Philip Kear, a plant breeder and geneticist and a country liaison scientist at the International Potato Center, who was not involved in the study, tells Carbon Brief.

Potatoes are often grown on “marginal land” in China, where soils are poorer or water is more scarce, Kear explains. And because farming in China is predominantly undertaken by small farmholders, he adds, the degree of mechanisation on farms is much lower than elsewhere in the world.

There is also, Kear says, “a lot of room for improvement” in selecting or breeding higher-yield varieties than those that are currently planted.

‘Dietary shift is hard’

Despite the potential gains, there are also risks associated with the policy that could negate some of its environmental benefits.

One is that potatoes spoil more easily than other staples such as rice, Scherer says. In order to be successful, she tells Carbon Brief, changes need to be made “at different stages in the value chain” – not just on the production side, but in terms of consumer behaviour, food storage and how processed food products are made.

(Another recent Nature Food study showed that more than one-quarter of food produced in China is wasted annually, nearly one-half of which is due to handling and storage after the crop is harvested.)

The authors also warn that an increase in potato production without an accompanying change in consumption patterns could end up negating the benefits of switching out other staples for potatoes. This is because if domestic rice production falls but demand is sustained, China will have to import rice from neighbouring countries.

Yang tells Carbon Brief:

“We can compare rice production in China versus rice production in those other countries. It turns out that rice production in China is very efficient, whereas in those other countries, yields are lower. So in this case, we’re kind of leaking our problem to other countries.”

Convincing an entire nation to change its diet is no small feat, Yang admits. Because of this, he says, the policy is “probably lagging behind” the targets it initially set out. Beijing News reported last year that potato yields had only slightly improved and that consumption patterns in the country had not significantly changed since the policy was revealed.

One way to make potatoes more palatable is by substituting them in for other staples in processed foods, such as noodles or buns. Yang explains:

“I do see that dietary shift is hard…But technologically speaking, you can add a little bit of potatoes into wheat [products]. And that doesn’t really alter the flavour of the noodles you eat. And that can, to some extent, help this policy or help in promoting potatoes.”

Kear tells Carbon Brief that the study is “quite useful and quite beneficial” in considering both the nutritional benefits and the environmental impacts of the Potato-as-Staple-Food policy. He adds:

“Creating that bridge between these two different stories, I think that’s really important. And it’s not the sort of thing that I’ve seen before.”

This story was published with permission from Carbon Brief.