Swedish automotive giant Volvo on Wednesday committed to phasing out its purely internal combustion engine (ICE) cars and is shifting lanes towards electrification.

To continue reading, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

The car manufacturer, which is now owned by Chinese firm Zhejiang Geely Holding Group, announced last week that all new Volvo models will be hybrids or battery-powered electric vehicles beginning 2019.

In a statement, Volvo president and chief executive Håkan Samuelsson said the move signals the end of the company’s production of solely combustion-powered cars, which it has been doing since 1927.

“

People increasingly demand electrified cars and we want to respond to our customers’ current and future needs.

Håkan Samuelsson, president and chief executive, Volvo Cars

Volvo is taking this bold step in response to increasing customer demand for fuel efficient and low-carbon transportation alternatives, he added.

“This is about the customer. People increasingly demand electrified cars and we want to respond to our customers’ current and future needs. You can now pick and choose whichever electrified Volvo you wish,” Samuelsson said.

Volvo said it will launch five fully electric cars between 2019 and 2021, three of which will be Volvo passenger car models and two of which will be sport cars under Volvo’s performance car arm, Polestar.

Aside from moving its business to electric cars, Volvo also announced plans to reduce the carbon emissions of its manufacturing facilities by 2025.

Volvo is targeting a total of 1 million electrified vehicles on the road by 2025. It plans to redesign its current models to become fully electric, plug in hybrid cars, or mild hybrid cars.

Unlike plug-in hybrids which have an electric motor, internal combustion engine and batteries that can be charged from a plug point, mild hybrids don’t have an electric motor and battery storage. Rather, they have a combustion engine with an electric starter motor that turns off the engine when the car is coasting, braking or stopped, making it more fuel-efficient.

The company will be joining leading electric vehicle (EV) makers Renault-Nissan Alliance, Tesla, and BMW among others in the electric car market, which has seen a 60 per cent growth last year.

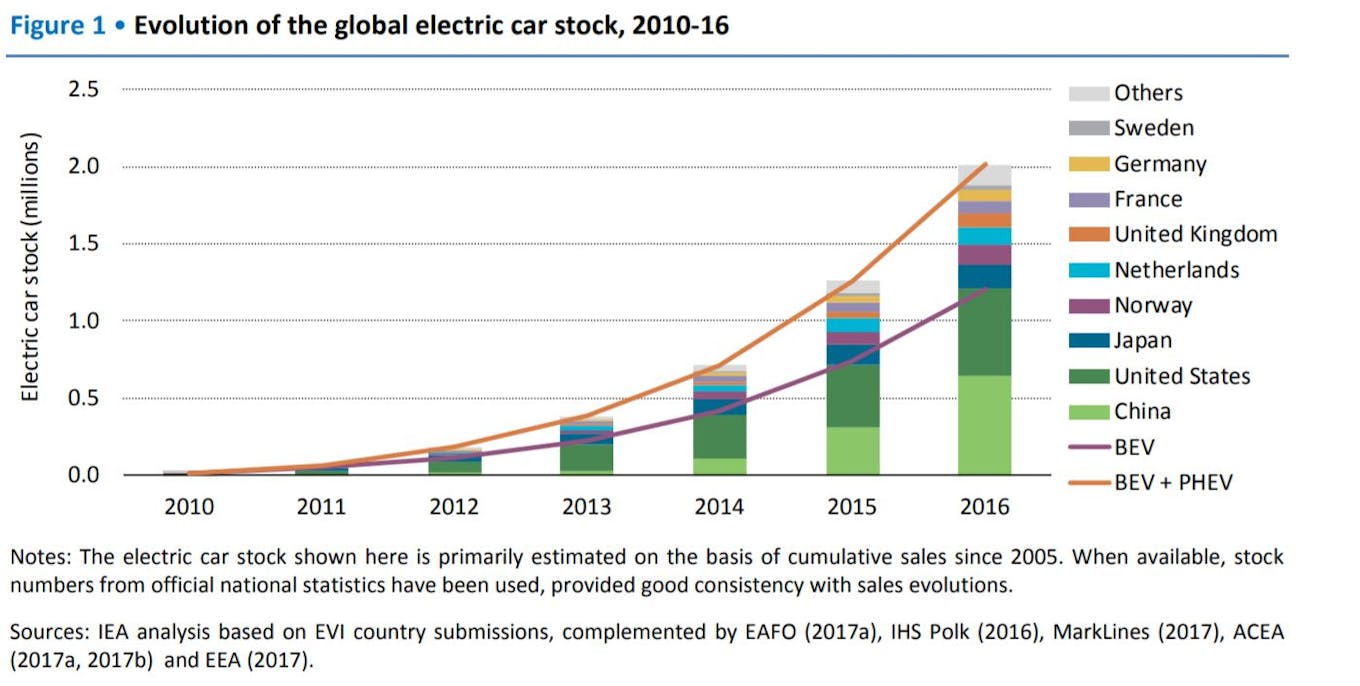

Graph showing the evolution of the global electric car stock. Image: IEA.

According to Paris-based intergovernmental organisation International Energy Agency’s (IEA) Global EV Outlook 2017, some 2 million electric vehicles took the roads in 2016, with China emerging as the largest electric car market worldwide.

Forty per cent of the world’s electric cars were sold in China last year, more than double the number of units sold in the United States, the report said.

While the “cool” factor of owning electric cars may be pulling sales up, the IEA credits the current market uptake largely to supportive government policies.

Volvo can expect to benefit from similar policy support, as its home markets – Sweden and China – are among the countries that give the most generous government incentives for electric car manufacturers.

In Sweden, the government offers incentives to private companies that give their workers electric vehicles as “benefit cars,” or cars that workers can also use for private driving.

The government offers private companies up to US $4,500 rebate for the purchase of fully electric vehicles and about half that sum for plug-in hybrids. Six per cent of all cars sold in Sweden last year were electrified. The country holds the third biggest share in the world in terms of the number of passenger electric cars successfully deployed, after Norway and The Netherlands.

China’s central government, on the other hand, offers a subsidy of up to US$6300 for the purchase of new-energy vehicles-comprising electric vehicles, plug-in hybrids and fuel-cell cars. This incentive will be in effect until 2020.

“Policy support will remain indispensable at least in the medium term for lowering barriers to electric car adoption. As electric car sales keep growing, governments will need to reconsider their policy tools,” the IEA report highlighted.