The year 2021 saw many organisations ramp up efforts to report on their carbon emissions. The tightening of related disclosure requirements, along with the demand from lenders and insurance underwriters who want more insight into value chain emissions, have put pressure on companies to adopt more standardised methods of accounting.

To continue reading, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

To limit global temperature rise to below 1.5 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels, global greenhouse gas emissions must be reduced 45 per cent from 2010 levels by 2030. The world is currently not on this trajectory and emissions reporting is seen as a useful tool for companies to remain accountable for pledges that they have made.

A look at the latest figures from CDP, an international non-profit that advocates for the transparency and disclosure of carbon emissions, reveals that almost five years after the Paris Agreement, there is tremendous growth in the number of companies across Asia-Pacific which disclose their emissions through questionnaires aligned with global accounting standards.

This year, CDP reports a record number of disclosures from more than 3,000 companies in the region, an increase from previous years largely driven by a huge jump in numbers from Greater China. In 2016, about 700 companies in Asia-Pacific disclosed their emissions through CDP.

Pratima Divgi, regional director at CDP Hong Kong, told Eco-Business that there are plans for CDP to further develop its systems and processes to support greater transparency and accountability from businesses, cities and governments and to expand the organisation’s disclosure platform.

By working closely with the London-headquartered Climate Disclosure Standards Board (CDSB), CDP intends to expand and integrate sustainability reporting standards to better capture data on a wider range of issues, said Divgi. This could include factoring in Scope 4 emissions, or what is commonly known as avoided emissions, to ensure that such reporting adheres to stricter standards.

For now, positive narratives surrounding how a company can augment brand value by demonstrating accountability through emissions reporting have fuelled the corporate appetite for going beyond the current protocol of reporting on Scope 1, 2 and 3 emissions. Some companies are starting to make claims on avoided emissions, though almost all of them cherry-pick and publicly report the positive impacts of their products.

Statisticians and energy experts have cautioned that this is problematic. Not only is it bad news for consumers who may be using unreliable information, companies risk tarnishing their brand if they are called out for greenwashing or overstating claims on emissions avoided. A clearer set of guidelines is needed if this is not just meant to be a shell game with no real benefits for the planet, the experts said.

What are Scope 4 emissions?

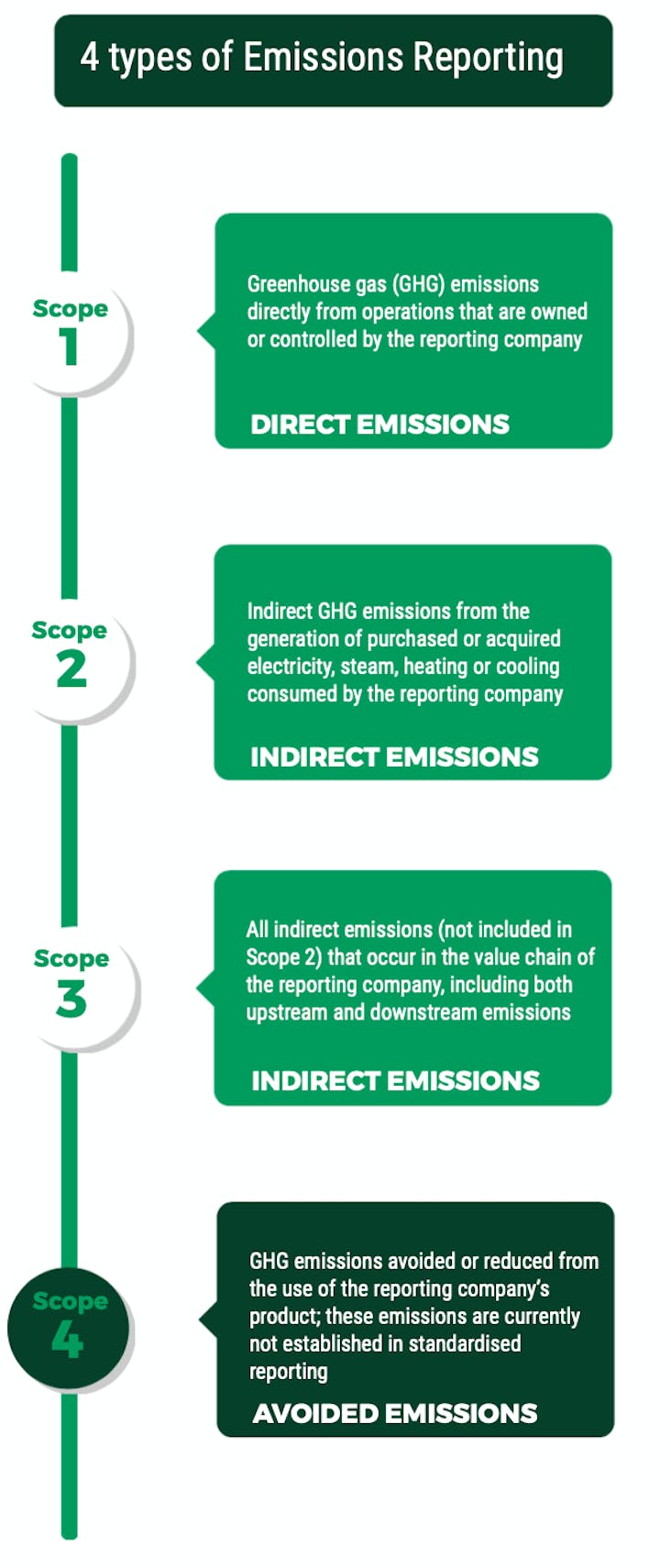

The GHG protocol corporate standard was created by the World Resources Institute and the World Business Council for Sustainable Development in 2004. It has since become the dominant accounting methodology for greenhouse gases (GHG) emissions reporting, with Scope 1 emissions referring to emissions from direct operations - factory emissions for example. Scope 2 emissions, on the other hand, are indirect sources of emissions and usually refer to emissions from purchased energy, such as the burning of coal or natural gas for electricity needed to power the lights in a building.

There are three scopes of carbon emissions. Reporting on Scope 1 and 2 is mandatory for many jurisdictions, while companies are starting to pay attention to Scope 3 emissions - reporting emissions across the value chain. Scope 4 is a relatively new concept. Image: Eco-Business

To see a fuller picture of a company’s carbon footprint, Scope 3, which includes all other indirect emissions that occur in a company’s value chain, was introduced in 2011. This category of emissions remains mostly voluntary to report, but given that they typically form the bulk of a company’s emissions - almost 90 per cent of all three scopes of emissions combined - regulators have been wanting to tackle this mammoth in the room. In October this year, the Group of 20’s Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD) announced that it had revised its reporting standard to encourage the disclosure of both upstream and downstream Scope 3 emissions.

Scope 4 emissions describe emissions that can be avoided through a product or a service. It is an entire category that falls outside current agreed protocols. It is also a relatively new concept.

More than a third of companies surveyed by the CDP in 2017 claim that they make products that help consumers minimise their carbon footprint.

In an article published by the World Resources Institute on Scope 4 emissions, researchers point to how companies have been claiming that products such as cold-water laundry detergents, fuel efficient tyres and energy-lean data centres ultimately help their consumers reduce emissions.

The paper noted that drawing from current GHG Protocol guidelines for reporting the comparative emissions impacts of products, it is clear that the complexity in accounting must be addressed before companies make claims about Scope 4 emissions. It further stated that companies have only focused on positive impacts in public reporting, ignoring the fact that negative impacts of products are equally common.

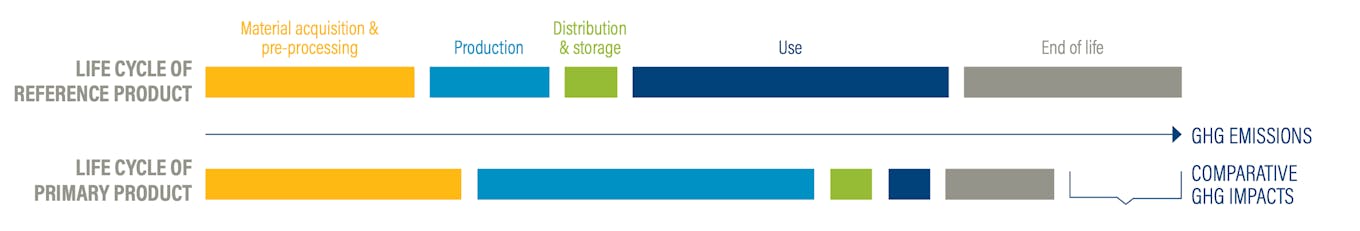

Energy statisticians also pointed out that companies often end up comparing the emissions of an assessed product against an existing product or a competitor’s product, a process that might be subject to selection bias. By using what is known as the “attribution estimation” approach, they sometimes end up exaggerating their claims. The experts suggest that “consequential estimation” should be applied instead, where the reporting company accounts for the sum of all system-wide changes in emissions occurring because of the product.

The graph shows how most companies calculate the comparative greenhouse gas impact of two products to make claims for avoided emissions. Image: World Resources Institute

Are companies ready for emissions reporting?

Experts told Eco-Business that the significant momentum towards mandatory disclosure is encouraging. Moving forward, companies would find it increasingly hard to avoid reporting emissions across the entire value chain. Scope 3 reporting will create a knock-on effect where companies with climate targets are pressured to ask their suppliers to cut emissions too.

However, in many markets, there is still a need to go further. In Southeast Asia, about 200 companies report their emissions through disclosure platforms like CDP, an increase from 53 in 2016.

In Singapore, adoption of climate change reporting based on the TCFD framework is very low. A recent sustainability reporting review by Singapore Exchange (SGX) showed that only 2 per cent of listed issuers adopt the reporting framework or other similar frameworks. This is likely to change with the SGX mandating listed firms to disclose climate targets from 2022.

“Companies in Southeast Asia have great potential to catch up,” said Divgi. The CDP plans to roll out capacity building programmes for listed companies in the region.

The lag in Scope 3 reporting, however, begs the question of whether markets are ready to move on to Scope 4 accounting. Alvin Ee, a research associate at the Energy Studies Institute at the National University of Singapore, said that without a defined framework, Scope 4 currently has little influence on the emissions monitoring and reporting of a company and is “generally not a major concern”.

“Avoided emissions are not considered when accounting for total emissions, under current disclosure standards. What it may potentially influence, however, is the ability of consumers and stakeholders to make informed choices, since the avoided emissions value that a company reports may not be accurate,” said Ee.

The case for Scope 4

For now, Scope 4 reporting is of considerable interest to companies trying to develop and promote low-carbon products. There are anecdotal accounts of companies making claims that their products have helped avoid greenhouse gas emissions compared to other products in the marketplace. This, however, is usually done without considering how it might complicate the way overall emissions are accounted for.

“

Avoided emissions are not considered when accounting for total emissions, under current disclosure standards. What it may potentially influence, however, is the ability of consumers and stakeholders to make informed choices, since the avoided emissions value that a company reports may not be accurate.

Alvin Ee, research associate, Energy Studies Institute, National University of Singapore

While not a perfect solution, the concept of Scope 4 emissions does reconcile with the GHG Protocol principles and if properly implemented, could mean companies taking concrete actions to ensure that new products are launched with emissions reduction in mind, experts told Eco-Business.

Limited data, however, is available on how companies practise Scope 4 reporting. The latest CDP survey done in 2017 on avoided emissions showed that among companies that responded, 36 per cent stated that they have made claims on avoided emissions of their products.

“The concept of Scope 4 emissions provides a better understanding of potential savings in terms of emissions avoidance. It is also a platform for companies which have embarked on product innovation or developing new technologies to showcase their efforts,” said Ee.

Companies expose themselves to accusations of greenwash when they use problematic methods to account for their avoided emissions. Here are three suggestions on what companies should note when reporting their Scope 4 emissions:

1 Do not cherry pick

Credibly tracking progress of whether a company has done its part in emissions reduction would require the company to consider both the negative and positive impacts of all the products in its portfolio.

Some avoided emissions claims aggregate comparisons of multiple products, such as a company’s entire line of low-carbon products. Image: World Resources Institute

When choosing products to assess, companies should not limit their analyses to low-carbon products that are known to or expected to reduce emissions. For example, a TV manufacturer might compare the life cycle emissions of its latest model to an older model built with outdated technology. This ultimately makes Scope 4 reporting a meaningless exercise.

Ee suggested that companies should select an industrial average value or a value calculated based on the best available techniques, for comparison. “It will not be wise to select the emissions value of a product with high emissions as the baseline, just to have a higher avoided emissions value,” said Ee. “To ensure transparency, it is good practice to justify the reason for the choice of baseline too.”

2 Be transparent about assumptions

Assumptions used in the evaluation of Scope 4 are key influencing factors, particularly for products with long life spans or products with multiple purposes. It is important to state these assumptions upfront.

For example, in the case of a reusable bag, the number of times it is used in its “lifespan” will eventually determine how much avoided emissions can be claimed by producers of these bags, while comparing them to single-use plastic bags.

3 Consider spillover impact or change in consumer behaviour

To provide a more holistic view and inform consumers or stakeholders on the trade-off when using a specific product, it is important for companies to account for the potential spillover impact of a product. The use of a product may create ripple effects that then increase or reduce emissions outside of the product’s life cycle. For example, a product that regularly needs maintenance and cleaning might result in higher water usage, hence cancelling out the emission reduction claims the company made while producing it.

Before embarking on Scope 4 reporting, companies should ensure they report a complete corporate value chain inventory, including Scope 1, 2 and 3 emissions. “The golden rule is to provide clear and complete information and ensure transparency and accountability,” said Ee.