Indonesia, home to a third of the world’s rainforests, has seen its annual deforestation drop by 8.4 per cent, its environment ministry said on Monday (26 June).

To continue reading, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

Indonesia recorded 104,000 hectares of forest loss from July 2021 to June 2022, down from 113,500 hectares in the year prior, according to government figures.

A study by Global Forest Watch, a forest monitoring platform from nonprofit World Resources Institute, finds that no tropical country has reduced primary forest loss as much as Indonesia in recent years.

Experts attribute the fall to better control of fires and stricter permitting for forest clearance.

One of the most significant measures is limiting new (clearance) permits on primary forest and peatland,” environment ministry official Belinda A Margono told reporters.

A clearance permit provides the right to deforest to use the land for another purpose, such as agriculture, housing or industry.

Stricter permits are part of a government strategy to more tightly control its forest reserves in recent years, following Indonesian President Joko Widodo’s issuing of a permanent moratorium on forest-clearing permits for plantations and logging in 2019.

The moratorium, which covers around 66 million hectares of primary forest and peatland, was introduced in 2011 and has been renewed regularly as part of efforts to reduce emissions from fires caused by deforestation. Forest fires and land clearance is Indonesia’s biggest emissions source.

While the moratorium has been criticised for not protecting secondary forests, it has been effective in curbing primary forest loss, said Nirarta Samadhi, country director at WRI Indonesia. In areas under the moratorium, primary forest loss fell by 45 per cent in 2018 compared to 2002-2016, according to WRI.

The deforestation rate has fallen further since the moratorium was made permanent in 2019, with Indonesia’s size of burnt forests reaching a 30-year historic low in 2020 at 115,459 hectares. That is a 75 per cent drop from the year before, according to Indonesia’s Ministry of Environment and Forestry.

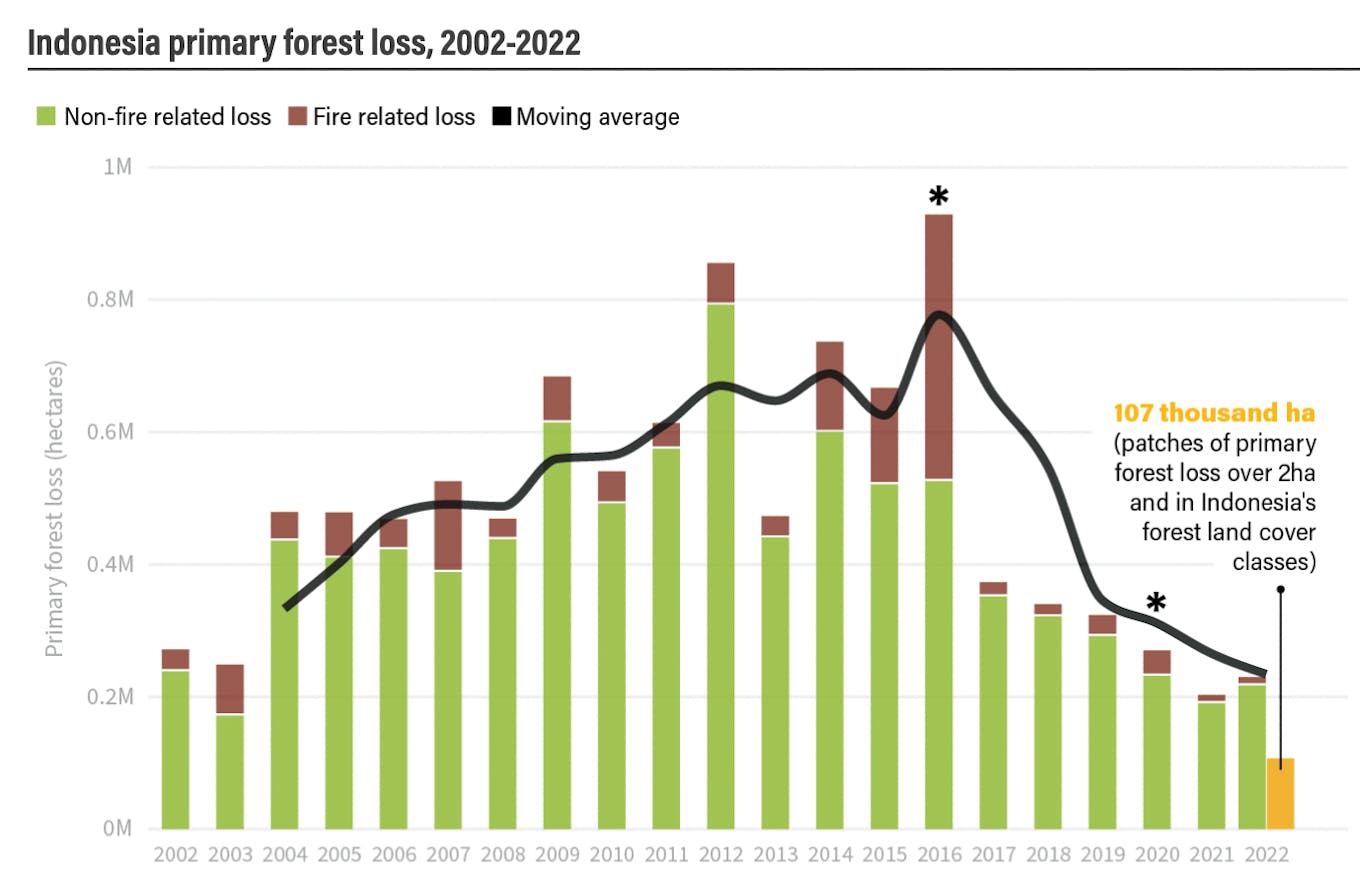

Indonesia has been recording a significant decline in primary forest loss since 2016. A significant portion of Indonesia’s 2016 primary forest loss was due to fire-related loss arising from slash-and-burn deforestation in 2015. Source: Global Forest Watch

The Southeast Asian country saw its average primary forest loss rate drop by 64 per cent between the periods 2015-17 and 2020-22.

This is some feat for a country which historically has had one of the world’s highest deforestation rates, with more than 74 million hectares of rainforest - an area nearly twice the size of Japan - logged, burned or degraded in the last half-century, according to nonprofit Greenpeace.

Other factors slowing forest loss in Indonesia

Another reason why deforestation in Indonesia has been falling is because it has been experiencing the La Niña phenonemon for three years through early 2023. La Niña is a periodic climate pattern that leads to the cooling of ocean surface temperatures.

For Indonesia, La Niña is often associated with increased rainfall in Java, Sulawesi, Maluku, and other key growing regions.

The higher rainfall could have dampened ‘slash-and-burn’ deforestation efforts, said Samadhi, referring to a technique that involves the cutting and burning of trees.

‘Slash-and-burn’ deforestation is the fastest, easiest, and cheapest way for poor farmers to clear land for agriculture.

This is because the ash and debris left over from burning form a nutrient-rich soil layer that makes it easier to grow crops during the next rainy season.

The third reason for the fall in deforestation is the falling price of palm oil, historically a major driver of deforestation in Indonesia.

A 2019 study showed that oil palm plantations were the single largest driver of deforestation in Indonesia between 2001 and 2016, accounting for 23 per cent of total deforestation in the archipelago.

Palm oil prices fell by some 49 per cent from 2022 to 2023 following a rebound in 2021 that saw prices surging to a record high in mid-2022 as economies reopened after the Covid-19 pandemic, fuelling consumption.

Analysts have attributed the drop in palm oil prices over the past year to sluggish demand, weakness in related vegetable oil markets and falling crude oil prices.

Commodity prices and deforestation rates go hand-in-hand. A 2021 study by researchers from geospatial company TheTreeMap found that rates of both plantation expansion and forest loss in Indonesia were positively correlated with palm oil prices.

Samadhi said that short-term fluctuations in palm oil prices also disincentivise the establishment of palm oil plantations, as it takes about four years for oil palms to produce fruits.

“Plantation owners have to incur sunk costs in deforesting the land, and they are unsure of the profit they can make when their fruits are ready to be harvested,” he said.

Stronger corporate pledges

Corporate commitments have also played a role in curbing deforestation. No Deforestation, No Peat and No Exploitation (NDPE) commitments now cover the majority of the palm oil sector in Indonesia.

As of 2020, NDPE policies covered 83 per cent of palm oil refining capacity in Indonesia and Malaysia, an uptick from the 74 per cent in November 2017.

The pulp and paper industry – another forest-risk sector – has also seen key pledges being made to halt forest loss, with an increasing number of producers and buyers of wood pulp and paper having adopted zero-deforestation commitments in recent years.

This has contributed to a drop in forest-clearing for the industry in Indonesia, according to analysis of data from Trase, a supply chain transparency initiative.

Arie Rompas, forest campaign team leader at Greenpeace Indonesia, said that the corporate pullback is partly due to non-governmental campaigns amplifying market pressure.

“Other civil society campaigns have also played significant roles, by demanding greater transparency and accountability from both governments and companies, and more recently, by taking legal action to enforce recognition of indigenous and local communities’ land rights,” he said.

He noted that Indonesia’s gross deforestation rate – which includes secondary forest loss – actually increased year on year in Indonesia, with a 19-per cent increase in gross forest loss in 2022 compared to 2021. “This means we have lost an area of forest larger than Greater London (157,000 ha), or more than three times the province of Jakarta (66,400 ha).”“Regardless of the fluctuating rate from year to year, there remains a huge area of ‘planned deforestation’ – already-permitted land banks where companies can legally clear forest in future, in critical landscapes including remaining forests in Papua,” he said.

Mining is now Indonesia’s biggest deforesting sector, overtaking palm oil.

More than half the tropical deforestation caused by industrial mining over the last two decades took place in Indonesia, according to a 2022 study published in the Proceedings of the Natural Academy of Sciences, a scientific journal.