Extreme weather events induced by climate change will hurt the productivity, and in turn, the bottom lines of Asia’s garment manufacturers – an issue that the global fashion trade has overlooked as it focuses on climate mitigation measures such as expanding renewables use and textile recycling, according to a new report.

To continue reading, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

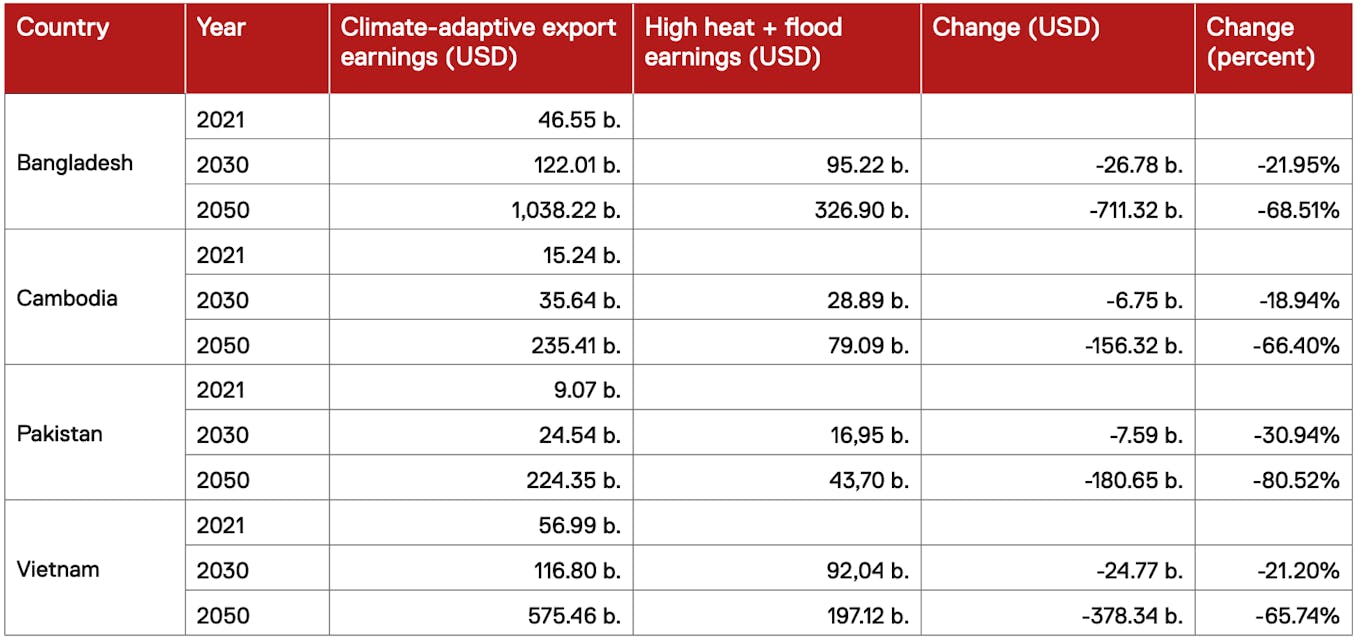

Four countries key to the fashion industry’s value chain in Asia – Bangladesh, Vietnam, Cambodia and Pakistan – could experience a 22 per cent or US$65.6 billion drop in export earnings, due to heat stress and flooding by 2030, found the study by Cornell University’s Global Labor Institute and finance group Schroders.

The shortfall in earnings could go up significantly to 69 per cent by 2050, according to projections. Manufacturing hubs stand to miss out on about 8 to 9 million jobs.

The new report, titled Higher Ground?, cautioned that life is set to become more difficult for garment workers toiling indoors as global temperatures rise, while flooding can cause road blockages and landslides, and delay workers from getting to work, resulting in lost earnings.

Collectively the four focus countries analysed are home to around 10,000 apparel and footwear factories and employ over 10.6 million workers in the industry. Fast fashion companies have been reliant on a business model that has been found to exploit cheap labour in such sweatshops with poor working conditions across the developing world.

The study analysed the climate vulnerability of 32 apparel production hubs, including the Donguuan-Guangdong-Shenzen regions of China, Chittagong, Yangon, New Delhi and Bangkok, and found that heat and flooding will have severe implications for the health and livelihoods of the people who make most of the world’s clothing.

Using the wet-bulb global temperature (WBGT) phenomenon – that is, a sliding scale of heat stress that determines when labourers are too hot and humid to work safely – the report found that the average number of WBGT days in Karachi, Dhaka, Ho Chi Minh City and Phnom Penh is set to rise by 51 per cent by 2030.

“

Adaptation to climate breakdown is not part of the global fashion industry’s plan.

Cornell University’s Global Labor Institute and Schroders’ ‘Higher Ground?’ study

No production hub will suffer from extreme heat like Karachi. More than half of all days of the year (52 per cent) in the Pakistani capital are projected to have WBGT readings above 30.5°C – a temperature considered high heat stress, even for acclimatised factory workers – by the end of this decade, said the report.

Heat stress is projected to slow job creation in key production hubs. Temperature-related slow-downs will mean 946,000 fewer manufacturing jobs created in Bangladesh, Vietnam, Cambodia and Pakistan by 2030, or a 7 per cent decline in job creation growth, if the sector does not introduce climate adaptation measures.

By 2050, the fall-off in new jobs created in these countries rises to 8.62 million jobs – a 34.36 per cent decline – if the sector does not adapt to climate change.

More factory-building in flood plains such as in Bangladesh, Cambodia and Vietnam could mean more dramatic flooding, exacerbated by sea-level rise, which threatens to interrupt apparel production and transport, and jeopardise workers’ health and earning potential.

Ningbo, a major port and industrial hub in east China’s Zhejiang province, is particularly susceptible to storm surges from typhoons and is expected to see coastal flooding above 50 centimeters for 15 per cent of its population in 2030.

The Guangzhou-Dongguan-Shenzhen region, Chattogram and Dhaka are at particularly high risk of flooding by the end of the decade, the report found.

An inundation of a quarter of a metre in factories may cost hours or even days of productivity, while major flooding of one metre or more can halt or slow production and transport for workers for weeks.

High temperatures and inundation will increasingly expose workers to the risk of ailments such as dengue fever and heat fatigue, which could mean more sick days, lower production, higher medical costs and lost income, warned the report.

Colombo, Dhaka, Yangon, Delhi, Bangkok, Phnom Penh and the Dongguan-Guangdong-Shenzhen region are identified as the areas most vulnerable to both flooding and extreme heat over the course of this decade.

Combined impacts of extreme heat and flooding for apparel export earnings in Bangladesh, Vietnam, Pakistan and Cambodia under climate-adaptative and high heat and flooding scenarios, 2030 and 2050. Source: Higher Ground? report

The impacts of extreme heat and flooding are already being felt by workforces across the region.

The Thai government declared that it was unsafe for people to work outdoors when the country recorded its highest ever temperature, 45.4°C, in April 2023. In August, the Sichuan government in southwestern China ordered factories to stop production to prioritise power for households to aircondition their homes amid unprecedented temperatures.

Also in August, 16 people died in a factory fire in the Philippines, when flooding delayed firefighters from attending the scene, while in southwest Japan in July, one factory worker was killed after torrential rain triggered landslides.

Factory workers interviewed for the study in Dhaka reported suffering from exhaustion from dehydration and lack of sleep at home due to high heat during the summer months, and struggling to meet daily production targets which were not adjusted to allow for the high temperatures.

Union leaders in Dhaka, Karachi and Phnom Penh interviewed noted recent rises in temperatures and complaints from workers about factory heat levels. Unions in Karachi pointed to heat-related deaths of apparel workers in recent heat waves as evidence of the growth of the problem.

Material risk

Some measures are being taken to mitigate climate impacts in mature apparel industries.

In Bangladesh, where 91 per cent of the country’s goods exports are from the apparel sector, heavily-promoted investments in the certification of energy-efficient “green factories” have been made in recent years. But the report pointed out that not all green factories make improvements in ventilation, roofing, workplace crowding and active cooling systems that will curb indoor heat.

Those that do introduce such measures, could see major productivity gains. If one half of apparel manufacturers invest in new factories, retrofits and efficient cooling systems, the resulting improvements in worker productivity can claw back 28.4 per cent or US$7.6 billion of lost export earnings by 2030, and 73,372 of the jobs lost in the high heat-stress scenario, the report found.

Manufacturers and fashion industry leaders interviewed reported that demand for apparel in several of the report’s focus countries is “soft” and that lower productivity from extreme heat is already driving up labour costs as some buyers push for lower prices from their manufacturers.

The report’s authors said that there is risk that brands and retailers take action only as part of well-promoted worker “wellness” programmes and the commissioning of flood hazard certifications, because they do not want to bear the full cost of climate adaptation measures, particularly at a time of slow global post-pandemic economic growth.

The economic incentive for fashion brands and retailers to disregard the need to instituted adaptation measures is systemic, driven by overconsumption, pricing competition and an industry-wide “addiction to growth”, the report said.

Jason Judd, executive director of Cornell University’s Global Labor Institute, said that brands’ preoccupation with mitigation over adaptation has been driven by regulators in the United States and Europe, where most of the biggest fashion brands are headquartered.

“Regulators in the United States and Europe are mostly focused on mitigation measures, which has a knock-on effect for brands,” he told Eco-Business. “While mitigation efforts are important for meeting the 1.5°C [Paris Agreement] target, they fail to acknowledge how we will cope with the direct impacts of climate breakdown in the interim.”

Judd noted that fashion brands tend to regard climate impacts as “externalities”, and leave manufacturers to bear the productivity costs of heat and flooding while workers suffer longer hours and exhaustion to make up for lost productivity shortfalls, and bear higher healthcare costs as a result.

“In essence, they [climate impacts] are someone else’s problem. As a result, relief and remedy such as cooling systems and strong social protection systems are treated by brands not as costs to share but for others to bear,” he said.

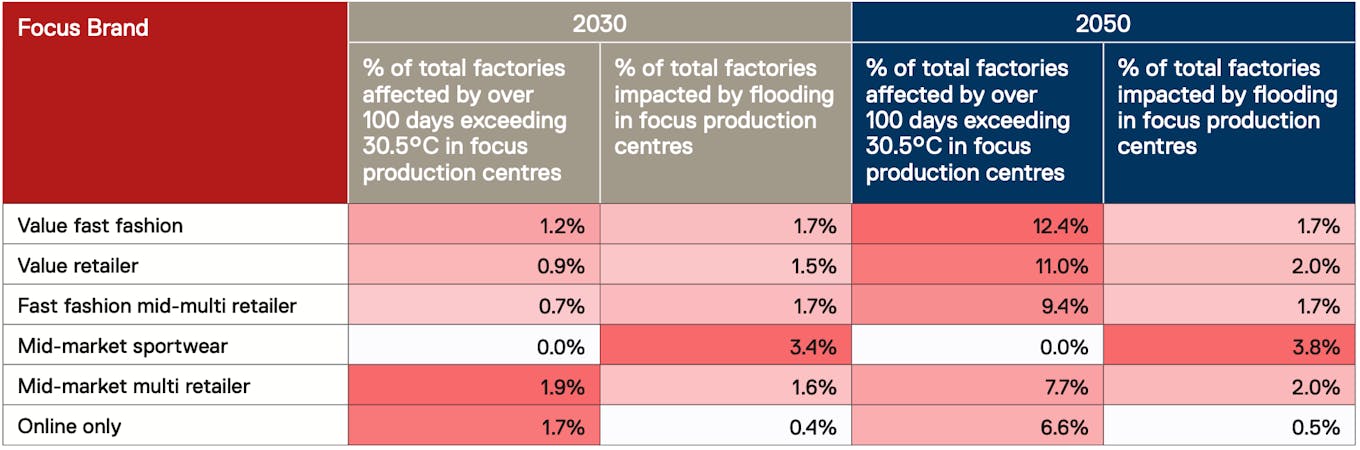

Climate impacts are projected to have a growing impact on the quality, delivery and cost of the goods that fashion brands procure from Asian manufacturing hubs. One unnamed low-cost fast fashion brand featured in the report could have a severely curtailed supply chain by 2050, due to the extreme heat its factories will be exposed to.

Overarching flood and heat impacts for fashion brands that use Bangladesh, Vietnam, Cambodia and Pakistan as production centres, 2030 and 2050. Source: Higher Ground? report

Brands and investors need to be writing adaptation costs into their plans, as these are clearly material risks and are largely unmeasured, Judd noted.

While new regulations in Europe are coming, climate adaptation and worker health are not priorities in due diligence regimes, he said. “They should be and our analyses argue that they make sense from three perspectives: protecting workers, protecting earnings, and managing risk for employers and governments, brands and investors.”

If the fashion industry is to achieve any genuine kind of “green growth”, brands will need to invest more in adaptation measures such as cooler buildings and effective social protection systems, as well as the well-publicised energy efficiency measures taken to rein in the climate impact of one of the world’s most polluting industries, the report said.