Malaysia is the latest jurisdiction in Asia to consult on the adoption of disclosure requirements set out by the International Sustainability Standards Board (ISSB), joining Australia, Japan, Hong Kong, New Zealand, Philippines and Singapore in proposing mandatory sustainability reporting rules.

To continue reading, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

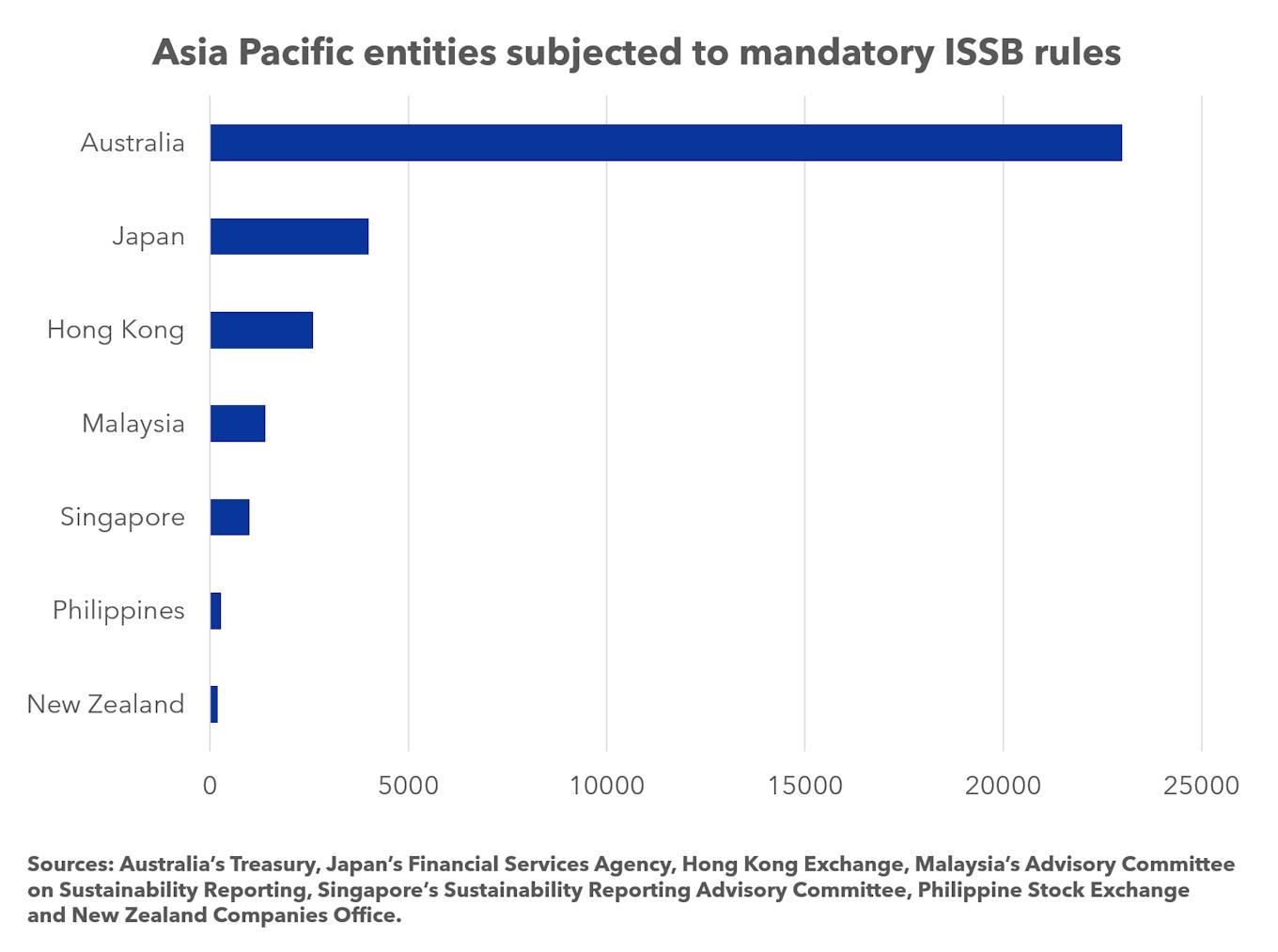

In the next few years, over 32,400 companies in the region will be subjected to a stricter sustainability reporting regime, with 200 financial institutions and listed firms in New Zealand having kicked off ISSB-aligned reporting last year and some 20,000 large Australian firms expected to do so in mid-2024.

“The various jurisdictions will be broadly consistent in terms of the overall timing of adoption and prioritising climate-related disclosures, but there may be differences in timing with regards to what needs to be disclosed by when and companies of different sizes and in different sectors,” said Mak Yuen Teen, professor of practice and director of the Centre for Investor Protection at the National University of Singapore (NUS) Business School.

The key divergences have been around the scope and timeline for non-listed companies to align with these new requirements and for external assurance – where a licensed third party comes in to verify the disclosed environmental, social and governance (ESG) performance of an entity – to guard against greenwashing.

So far, Hong Kong, the Philippines and Japan have yet to propose extending mandatory reporting rules beyond listed issuers nor a third-party audit of ESG disclosures. Among those mandating independent checks of sustainability reports, only Australia and New Zealand will require limited assurance – the baseline level of assurance – for a company’s direct, indirect and value chain emissions, also known as Scope 1, 2 and 3 emissions, from the outset.

“

I have my doubts as to whether regulators in Singapore or other countries in this region will strictly enforce disclosure rules.

Mak Yuen Teen, director, Centre for Investor Protection, National University of Singapore Business School

Meanwhile, Singapore regulators have erred on the side of caution, requiring firms to obtain limited assurance for just their Scope 1 and 2 emissions two years after they begin disclosing them, with plans to consult on the timeline for reasonable assurance – a higher level of assurance – at a later stage after reviewing the implementation experience of “more advanced jurisdictions” like Australia and New Zealand.

Around 32,400 Asia Pacific firms are estimated to be affected by mandatory ISSB rules. Image: Gabrielle See/Eco-Business

The otherwise consistent adoption of ISSB standards means there is likely a low risk of regulatory arbitrage within Asia, Mak told Eco-Business.

Concerns around delistings in certain jurisdictions due to more stringent ESG disclosure requirements arose late last year, when international companies started to withdraw their listings on European Union bourses to sidestep its comprehensive reporting rules – which unlike ISSB standards, consider the risks a firm creates for the world, beyond the financial risks that it faces from climate change, also known as “double materiality”.

Based on early estimates by regional regulators, report preparers may have to fork out hundreds of thousands of dollars – depending on the scale and maturity of sustainability reporting in a company – to comply with these new rules, which some jursidictions like Singapore are helping to mitigate with grants and capability building initiatives.

As companies, investors and auditors across Asia grapple with the new sustainability reporting regime, here are some key benefits and concerns that experts anticipate.

ESG data 2.0

The standardisation of reporting rules will allow for investors to more accurately assess the sustainability performance of companies, due to improved transparency and quality of ESG data collected, said Melissa Cheok, associate director at Sustainable Fitch, the ESG research arm of credit rating agency Fitch Group. These efforts may benefit investors looking to provide loans for green and sustainable projects, she added.

But to ensure that firms disclose sustainability risks and opportunities most material to them, Mak said that they “should first consider their context”, instead of assuming what the ISSB’s climate-related disclosure standards, the IFRS S2, deem as material. “That being said, climate is important for most organisations and many may have blind spots for this as they may think these risks will not crystallise in the short term.”

GRI and SASB standards are not dead

While mandatory reporting rules will likely converge towards ISSB standards, other frameworks will still be relevant for firms to identify material sustainability-related risks and opportunities to report on – something that ISSB has alluded to, said Mak. These could include Sustainability Accounting Standards Board (SASB) standards, the Climate Disclosure Standards Board (CDSB) framework and Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) standards.

SASB, one of the prominent frameworks that has since been consolidated into the parent organisation of ISSB, IFRS Foundation, is investor-oriented and focused on financially material risks. Companies that need technical guidance for water- and biodiversity-related disclosures can refer to the CDSB framework – which formed the basis for the Taskforce for Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD) and has also been subsumed by the IFRS Foundation.

Meanwhile, the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) standards – which continue to be the most widely used framework –can be used by firms for impact materiality, to assess the most significant impacts of their business activities on the economy, environment and society.

Big Four domination

The Big Four accounting firms – Deloitte, Ernst & Young, KPMG and PwC – who already dominate the financial audit market, continue to be the biggest players in sustainability consulting and assurance services, and have gone on acquisition sprees in the past few years to boost their capabilities and tap into new markets.

Megat Iskandar Shah, a partner at EY Malaysia, told Eco-Business that he has seen increasing demand for sustainability assurance, though it is not yet mandatory in the country. “However, should external assurance become obligatory, assurance providers will need to increase their resources to cater to the increasing demand,” he added. PwC Malaysia’s Manohar Johnson concurred, saying that firms like his are increasingly “hiring beyond traditional accounting and finance fields” to seek out those with “expertise in assessing environmental and social metrics”.

This has raised concerns around inherent conflicts if a firm’s financial auditor also assures its sustainability disclosures. Mak acknowledges that a company might reap cost savings and other efficiencies from having a single provider of financial and sustainability audits, but it would have to be more mindful of conflicts of interest and consider if it is healthy to increase the dependence on one firm for these services. ”I think over-concentration is bad and we have seen some of the consequences of that in the financial audit market,” he warned. “The question is whether the same firm would provide different opinions about sustainability disclosures and financial statements, or would it be under pressure to align the two opinions?”

Elsa Pau, founder and chief executive of BlueOnion, a Hong Kong-based ESG analytics firm, added that an auditor could run into a “self-review risk” if it has to revisit judgements it previously made on a company’s financial statements while conducting a sustainability assurance. This would threaten the auditor’s independence as it would, for instance, have to re-evaluate certain environmental liabilities relevant to a firm’s sustainability performance when it proceeds to assure the entity’s sustainability report.

Regulating assurance providers

Unlike financial auditing, there are currently no specific qualifications for sustainability assurance providers beyond broad assurance standards. The International Standard on Sustainability Assurance (ISSA) is in the midst of finalising a proposed global standard for sustainability assurance, dubbed the ISSA 5000, by the end of this year.

Concurrently, third-party assurance providers need to be “independent and competent” so that companies cannot cherry-pick what disclosures to assure, said Mak. This has been recognised by Singapore regulators, who require licensed audit firms to separately register as climate auditors. Conversely, the Australian Treasury allows a company’s financial auditor, who will “use technical climate and sustainability experts where required”, to audit its sustainability report.

“It remains to be seen whether there will be robust oversight of sustainability assurance providers by regulators. In many countries, oversight of financial statement auditors by regulators has been found wanting,” said Mak. “Without robust oversight, we cannot really expect reliable assurance.”

Elusive penalties

Given that many companies are just beginning to put out their sustainability reports, many regulators have yet to impose penalties for non-compliance.

In 2023, the Philippines laid out potential penalties for issuers that fail to submit their sustainability reports on time, from a warning for a company’s first offense to a fine of PHP 1 million (US$17,785) or loss of its operating license. New Zealand became the first country in the region to legislate sanctions with real teeth back in 2021, where directors of large financial entities can face imprisonment of up to 5 years and a fine not exceeding NZ$500,000 (US$300,570) for knowingly failing to comply with climate standards.

Singapore’s stock exchange regulator, which recently launched a public consultation on how to implement mandatory ISSB reporting rules which will come into effect in 2025, has not introduced penalties. “Even if there are penalties, they may be quite light or not enforced – few Singapore companies have been penalised for non-compliance with financial reporting standards which have been legally required for many years,” said Mak. “So I have my doubts as to whether regulators in Singapore or other countries in this region will strictly enforce disclosure rules.”

But rather than hard regulation, which would not be able to differentiate between audit firm and the sustainability assurance team that falls under it, Pau is in favour of an industry practioners’ code of conduct that is separate from the guidelines for audit firms and pure-play sustainability assurance providers. “I am completely for the idea of regulators taking a hard stand once they are clear about what they are enforcing, and the line is no longer blurry,” she said.

At a glance: When ISSB rules will kick in across Asia

A timeline for what entities will need to report on as Asia adopts International Sustainability Standards Board (ISSB) standards. Image: Gabrielle See/Eco-Business

Samantha Ho contributed to this report.