Developing sustainable aviation fuel (SAF) for commercial sale is not just scientifically challenging, it is expensive. But it has not stopped one researcher from trying to succeed.

To continue reading, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

“[It] is literally rocket science,” said Dr Rozzeta Dolah, senior lecturer at Universiti Teknologi Malaysia and managing director of nanotechnology solutions firm Naglus Industries, which converts plant waste into pollution control and climate change management solutions. “We are not ready to market the sustainable jet fuel yet because we need government support.”

Commercially available SAF must follow strict international standards, particularly the American Society for Testing Materials’ D7566 standard for technical certification. This means that even though Rozzeta and her team at the university have successfully turned plant biomass into a liquid that appears like bio-jet fuel, a colourless fluid similar in appearance to jet A1 fuel, regulatory and financial hurdles still stand before them.

“We have to send the bio-jet fuel for testing and approval to the aviation department, [put it through the] certification process and so on. There are also warranty and insurance costs,” she said, explaining the fees associated with certifying and marketing the product as an SAF.

“We know what procedures need to be taken, it is just that we don’t have enough money yet,” said Rozzeta, who was named among the 2022 winners of the Eco-Business A-List, which recognises the region’s most impactful sustainability practitioners. “There is a gap between the readiness of funders to back something that has yet to be commercialised, and the amount (of money) that we need just to validate and certify our bio-jet fuel.”

Nanotechnology solutions firm Naglus Industries converts plant waste such as old bamboo (centre) and empty fruit bunches from oil palm into bio-oil (left). After two years of research, they succeeded in producing a colourless fluid that is similar in appearance to sustainable aviation fuel (far right). Image: Samantha Ho/ Eco-Business

Commercial SAF is currently produced by large conglomerates based in the United States and Europe, with Finland-based oil firm Neste being the largest and most established producer. Neste, which currently supplies jet fuel to major American and European airlines and cargo carriers, aims to increase production of its SAF to 1.5 million tonnes per year by the end of 2023.

If Rozzeta and her team succeed, they will be the first commercial bio-jet fuel produced in Malaysia.

Producing the colourless bio-oil itself was a two-year struggle, but it was that challenge that first put her in contact with the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) in the United States, where she later became a postdoctoral fellow from the Lab of Microfluidics and Nanofluidics Research. Rozzeta was initially unable to obtain the results they wanted from the bioreactor installed at Universiti Teknologi Malaysia.

“The temperature was uneven, the pressure was not good enough, and the bio-oil output that we could get from the reactor was well below target. So we emailed experts around the world for how to solve the problem, and one of the responses we got was from a professor at MIT,” she said.

Her resulting work with the bioreactor produced not just the bio-oil but a series of products that Naglus Industries now markets in order to combat climate change and carbon emissions while raising funds for subsequent research.

What inspired you to focus on applying nanotechnology to renewable energy?

In 2016, we at UTM received an offer to work with (Malaysia’s national utility company) Tenaga Nasional to reduce carbon dioxide emissions at their power plant in Manjung, Perak, where coal was piled up like mountains. Our task was to capture the carbon dioxide from being emitted into the atmosphere, which we fed algae to be sold as biofuels. [Rozzeta was involved in the development of a nanotechnology device that increased the dissolution of carbon dioxide in marine microalgae culture.]

That became my interest and generating renewable energy from biomass was something I thought I could delve into, especially since it was new to Malaysia. I thought, ‘maybe I could tackle this blue-ocean field’ by using biomass waste products.

That is when we decided to build the bioreactor in the university so that we could do research using it here, instead of only being able to use the one owned by Tenaga Nasional.

In addition to being a lecturer, you are also the CEO of Naglus Industries Sdn Bhd. Can you share why you decided to commercialise your research via a private company?

At MIT, I realised that they had something we don’t have here in Malaysia – a startup mindset and the culture of building spin-off companies based on academic research. That is what makes them number one [as a university] – their innovation index is very high. Their students do not only complete their research at university, but develop it into a commercial product regardless of the level of their degree. Their endgame goes beyond research, to ensure that products reach society and customers and generate income as well.

MIT has been recognised as being helpful to society by solving real-world problems through their research, inventing devices that can solve those problems and then selling it back to the community. So it’s a closed loop.

After I came back to Malaysia in 2019, the first thing I did was to prepare a business plan proposal to create a university spin-off.

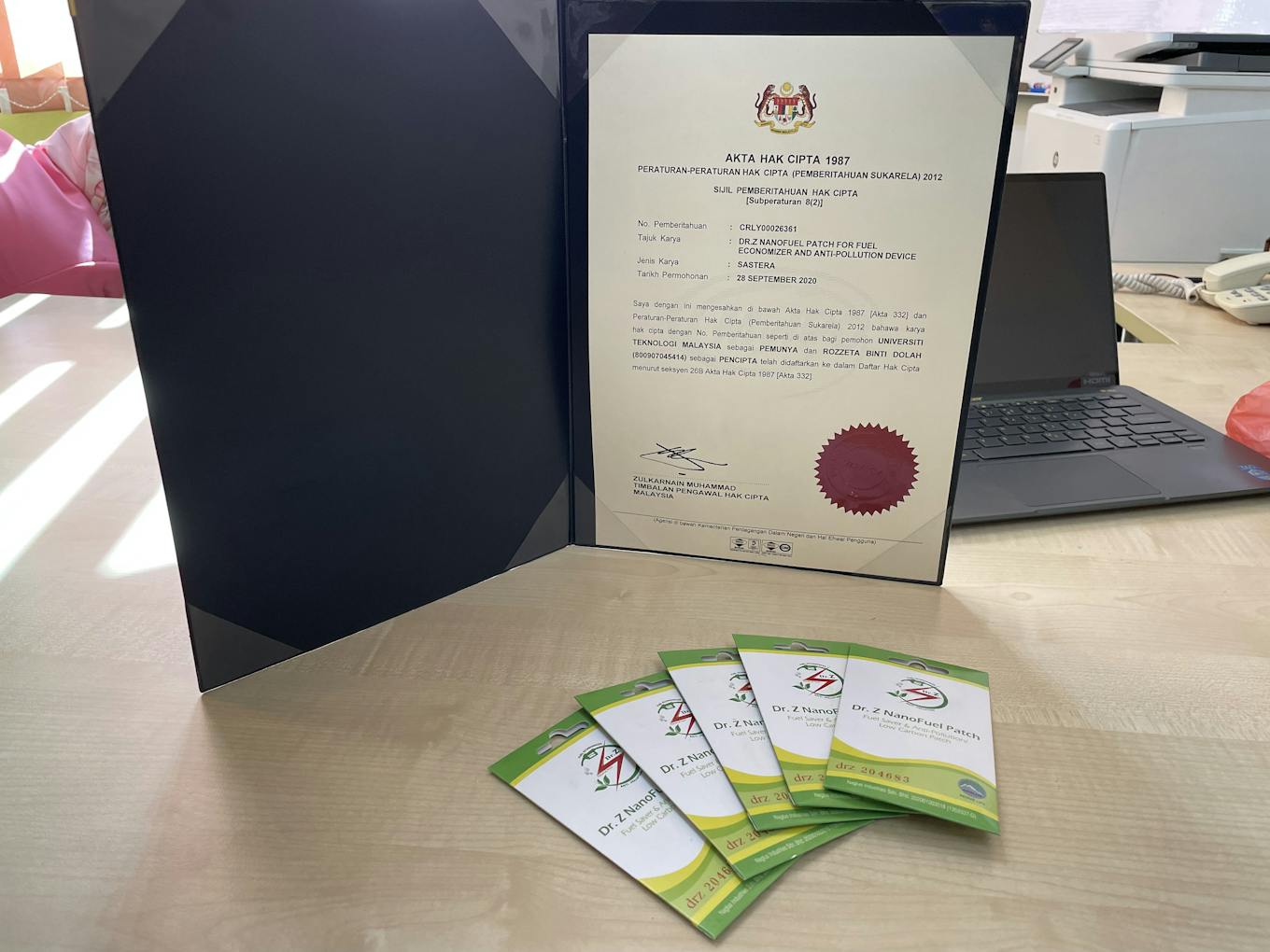

How did you come about producing your products which have been commercialised, such as the Dr Z. nano-fuel patch to lower carbon emissions by internal combustion engine vehicles, and the nano paint?

Along the way (of researching and trying to produce bio-jet fuel), we discovered different applications using the same reactor. The first application was the nano-fuel patch, for which we originally achieved an emissions reduction of at least 3 per cent. But the university panel that was in charge of approving our spin-off company told us that it had to be at least 5 per cent for us to be able to launch the product. We took it as a challenge and eventually managed to give them a 13 per cent reduction in emissions!

Manufactured using biomass waste, the Dr.Z NanoFuel patch is designed to lower the carbon emissions of internal combustion engines by up to 13 per cent. Patented by its inventor, Dr Rozzeta Dolah, it is self-adhesive and can be attached to the fuel tanks of motorcycles and cars. Image: Samantha Ho/Eco-Business

As for the nano paint, that idea came about after we had joined the Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) NINJA Accelerator programme. It was an intense four-month programme similar to the Amazing Race, in which we had to pass multiple challenges. We were forced to think about reasons why our first product, the nano fuel patch, might not succeed commercially, and to brainstorm a second innovation.

That’s how we came up with the idea for nano paint, for which demand was much more stable than the fuel patch. We realised that the fuel patch was something that was optional and demand would be constrained given the growing market for electric vehicles (EVs). Plus, people buy paint in bulk for buildings, so it was likely to generate higher revenue and profit.

In 2021, you received a 30,000 ringgit (US$6,736) prize from the L’Oréal-Unesco Fellowship for Women in Science. How did you spend this amount?

L’Oreal was the first award we won. We used that 30,000 ringgit for testing how much carbon emissions the Dr.Z Nano Fuel Patch reduced, because UTM required that our product reduced carbon emissions by more than 5 per cent before they approved our spin-off company. And this proof had to be done via tests in specific, industry-grade laboratories which were expensive to use. Even though the labs were owned by the university, it cost between 7,000 ringgit (US$1,573) and 12,000 ringgit (US$2,697) per test. So we funded those tests using the L’Oreal award money.

As you can tell, 30,000 ringgit was not a lot! I could have chosen to just sit on the research without pursuing commercialisation, but my team and I were driven to launch our spin-off company. So I decided that we had to get the JICA NINJA 2021 Accelerator prize, which was worth US$30,000 and funded by global consulting firm McKinsey & Company. The JICA NINJA programme was open to very young startups offering technological solutions related to the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals and climate change. I saw those requirements and thought that what exactly what Naglus was trying to do, even though we were the only university startup out of 15 participants from five different Asian countries.

“

We want our country’s leaders to bear in mind that we have researchers; we have the brains. Please, don’t waste us.

Dr Rozzeta Dolah, senior lecturer at Universiti Teknologi Malaysia and chief executive officer of Naglus Industries

What excites you most about your job?

Making money! [Laughs] But it is how we make money, through research and innovation. The endgame is actually to educate society. For example, with nanotechnology, you don’t see a lot of its application in Malaysia. So, we are educating society and want to bring something new to the country. That motivates me. We do not want Malaysia to be left behind or to be a follower when it comes to developing and applying new technology.

When I say educating society, it is educating people to value the brains and technologies that we have. My colleagues and I are quite proactive and radical when it comes to drawing attention to new technologies. But what about introverts who speak less but are just as intelligent? It’s very sad to waste that talent.

It has been rough and disheartening [for me], and I don’t want other people to feel the way I feel about our country. So we are trying to be agents for change. We want our country’s leaders to bear in mind that we have researchers; we have the brains. Please, don’t waste us.

Why do you think you will never be replaced by artificial intelligence, or AI?

The passion [I have towards my research] cannot be replaced. I don’t think any robots can do what I’m doing right now. AI as something structured can assist us in excelling at what we do, but it doesn’t have the intuition to spark innovation – that comes from the human passion towards the work we do.

The interview has been edited for brevity and clarity.

Rozzeta Dolah was one of 10 sustainability leaders selected for the Eco-Business A-List 2022. Read our stories on other A-List winners here.