The number of tropical cyclones originating in the North Atlantic and central Pacific has slightly increased, while fewer have occurred in the southern Indian Ocean and western North Pacific, according to the research.

Other factors, such as large volcanic eruptions and the human-driven release of aerosols, have also played a role in altering the global distribution of cyclones, the lead author tells Carbon Brief.

The research “provides strong evidence” that human-caused global warming has had “a considerable impact on global tropical cyclones”, another scientist tells Carbon Brief. However, it is worth bearing in mind that the findings come with some uncertainty, he adds.

Chasing cyclones

Tropical cyclones are storms that develop in tropical oceans at least 5-30 latitude north or south of the equator, where sea temperatures are at least 27C. Strong tropical storms are called “hurricanes” in the North Atlantic and the central and North Pacific, “typhoons” in the northwest Pacific and simply “tropical cyclones” in the South Pacific and Indian Ocean.

Research has shown that climate change likely boosted the likelihood of many single cyclone events, including Hurricane Harvey, which made landfall in Texas in 2017, and Hurricane Katrina, which struck New Orleans and its surrounding regions in 2005.

However, there is currently no consensus on whether climate change is driving an increase in the global number of tropical cyclones. The world currently experiences almost 100 tropical cyclones a year.

One reason for this is that global records of tropical cyclone numbers are relatively short, only beginning at the advent of the satellite era around 1980. Another is that tropical cyclones are also influenced by natural climate fluctuations, which could be masking the impact of climate change on cyclone numbers.

The new study, published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), instead looks at how climate change could have affected the global distribution of tropical cyclones from 1980-2018.

It finds that there has been a discernible shift in the spread of cyclones across the globe, explains study lead author Dr Hiroyuki Murakami, a climate researcher at the University Corporation for Atmospheric Research (UCAR) and the Geophysical Fluid Dynamics Laboratory in the US and the Meteorological Research Institute in Japan. He tells Carbon Brief:

“The main finding from the new research is that climate change has been evident in the changing in the global distribution of tropical cyclones over the last 40 years.”

Changing picture

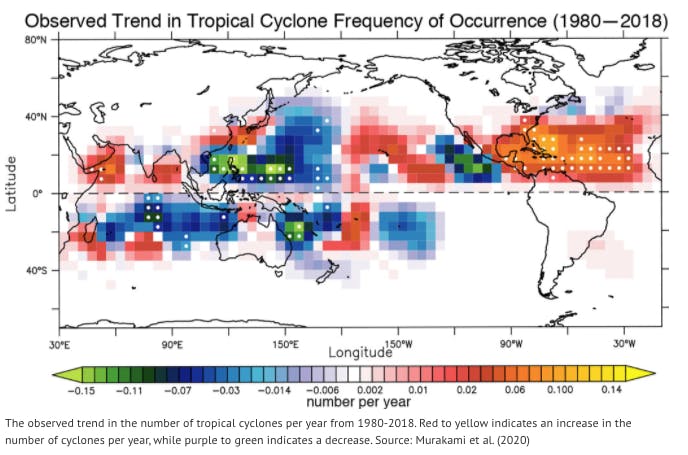

The researchers first studied data on the global distribution of cyclones from 1980-2018. This is illustrated on the chart below, where red to yellow indicates an increase in the number of cyclones per year, while purple to green indicates a decrease.

The map shows how the number of tropical cyclones originating in the North Atlantic and central Pacific has increased over the past four decades, while fewer have occurred in the southern Indian Ocean and western North Pacific. (It is worth noting that the annual changes are relatively small. For example, an annual increase of 0.1 equates to one extra cyclone every 10 years.)

The researchers then used high-resolution climate models to carry out a large number of experiments to investigate what factors are likely to have influenced the global distribution of tropical cyclones from 1980-2018.

They found that only model simulations that included human influences, such as greenhouse gas emissions and human-driven aerosols, could reproduce the actual observed pattern of cyclones from 1980-2018.

In particular, the researchers noted that human-driven climate change is the most likely driver of increases in cyclones in the central Pacific Ocean, which surrounds Japan and the Marshall Islands.

The increases in tropical cyclones in the North Atlantic, however, are more closely tied to decreases in human-driven aerosols released by pollution, Murakami tells Carbon Brief:

“We identified that most tropical cyclones in the North Atlantic over the last 40 years are due to decreases in anthropogenic aerosols in the North Atlantic Ocean. The decline in particulate pollution due to control measures [has] increased the warming of the ocean by allowing more sunlight to be absorbed by the ocean. This local warming led to increases in tropical cyclone activity.”

The authors also find that human-driven climate change is closely linked to decreases in tropical cyclone activity in the southern Indian Ocean and western North Pacific. Murakami explains:

“Greenhouse gases are warming the upper atmosphere and the ocean [in these regions]. This combines to create a more stable atmosphere, with less chance that a convection of air currents will help spawn and build up tropical cyclones.”

It is worth noting, however, that the study period does not include 2019 – a record year for cyclones in the Indian Ocean, says Prof Kevin Trenberth, a senior scientist at the National Center for Atmospheric Research (NCAR) in Colorado, who was not involved with the research. He tells Carbon Brief:

“In 2019, there were four spectacular cyclones in the Indian Ocean and two of these, in the southern Indian Ocean, were unprecedented – belying the decrease found here. The 2018-19 South-West Indian Ocean cyclone season was the costliest and the most active season ever recorded since reliable records began in 1967.”

Such cyclones included Cyclone Idai, which ravaged through Mozambique, Malawi and Zimbabwe in March 2019 – affecting more than two million people.

Future weather

The findings could help to explain why there has been no discernible change in the number of tropical cyclones occurring globally over the past 40 years, says Murakami:

“We don’t find any clear trend in the number of global tropical cyclones over the last 40 years. This is because there are regions showing increases or decreases. They are all cancelled out, leading to no change in the total number.”

The research adds to scientists’ understanding of how climate change is shaping tropical cyclone risk, says Dr Shuai Wang, an atmospheric physicist from Imperial College London, who was not involved in the study. He tells Carbon Brief:

“As stated by the authors themselves, there is still uncertainty that we should bear in mind when digesting the information of this paper. Nevertheless, this work provides a piece of strong evidence that the anthropogenic forcing has likely been generating a considerable impact on global tropical cyclone statistics.”

(The study primarily uses one climate model, although the authors say they see “consistent results” with a separate model. The authors also note that it would be “preferable to adopt a multiple-model approach to reduce the uncertainty”.)

This story was published with permission from Carbon Brief.