As the World Trade Organisation confronts a deadline this year to reach an agreement to eliminate subsidies that are decimating global fish populations, perhaps no nation faces higher stakes than China.

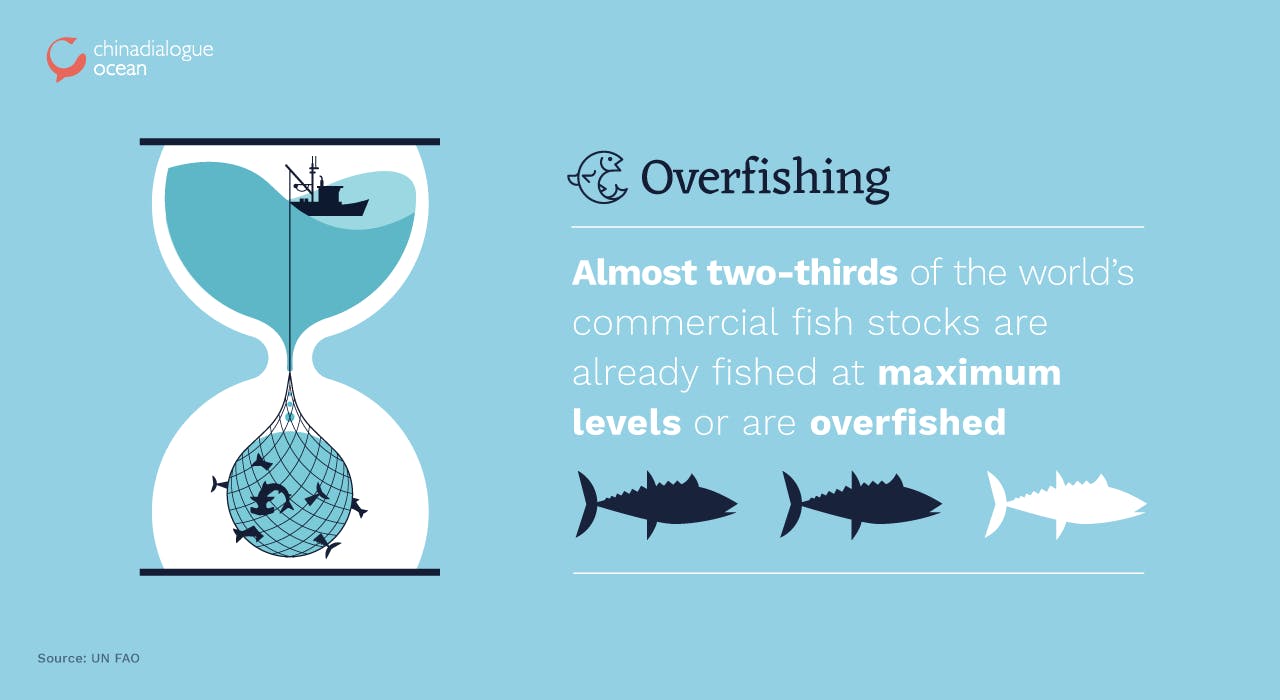

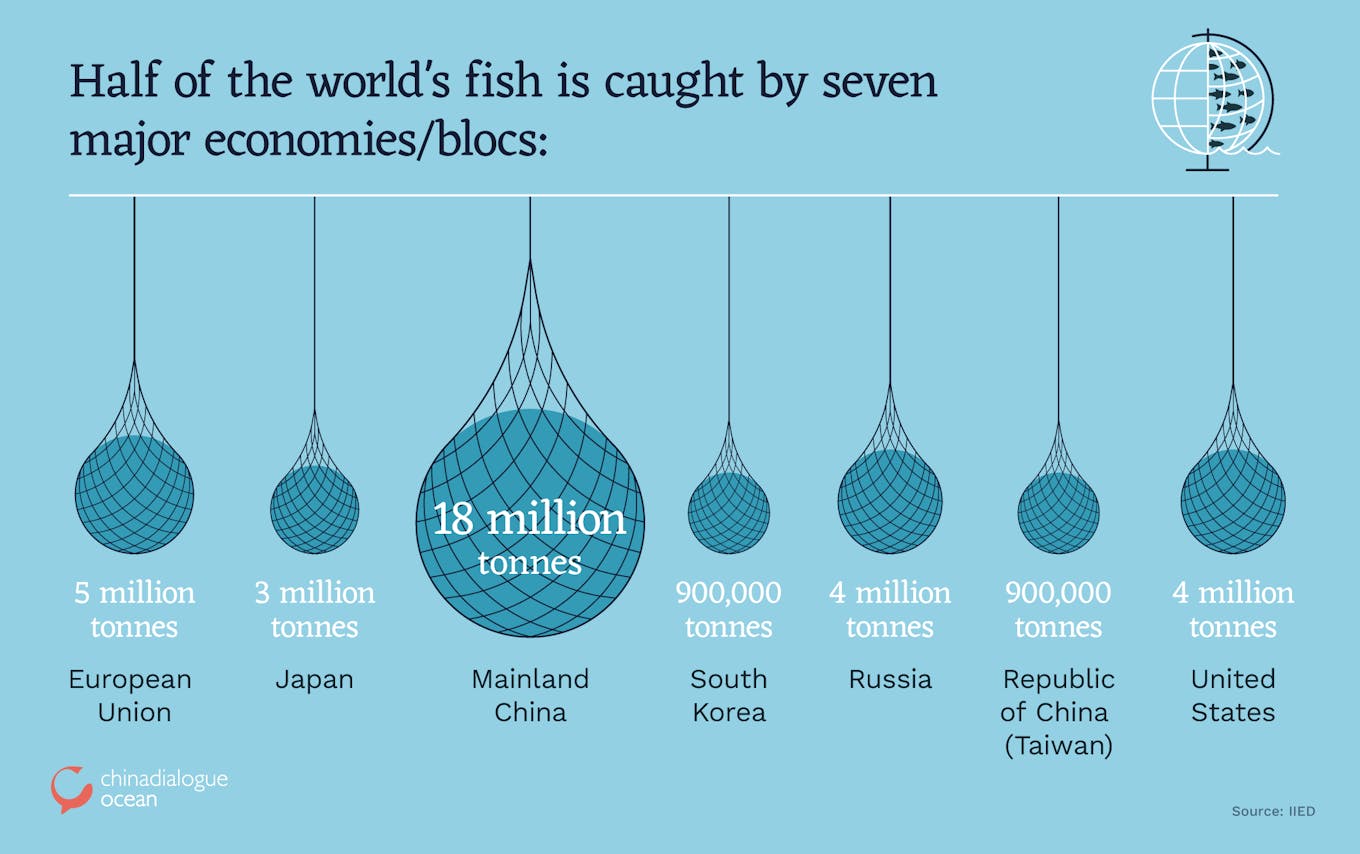

China operates the planet’s largest fishing fleet, catches the most seafood and hands out the most money in fuel subsidies and other support that enables industrial trawlers to travel to the furthest reaches of the ocean. As a result of the expansion of global fishing fleets to meet rising demand, 33 per cent of fish populations are being harvested at biologically unsustainable levels while 90 per cent are fully exploited, according to the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO).

Researchers in 2016 pegged total annual fishing subsidies at US$35 billion (in 2009 dollars). They categorised US$20 billion of those incentives as harmful with as much as 85 per cent of that money going to industrial fishing operations.

A 2018 study found that in the absence of US$4.2 billion in subsidies, more than half of high seas fishing would be unprofitable. Furthermore, China, Taiwan, Japan, South Korea, Indonesia and Spain account for 80 per cent of fishing outside territorial waters. Researchers estimate that China alone was responsible for 21 per cent of high seas fishing in 2014 and nearly 19 per cent of global fish catch averaged between 2014 and 2016.

“

There’s a domestic policy in China to reduce fuel subsidies for domestic fishing and it’s important for China to take forward some of these commitments they have made domestically to the international stage.

Isabel Jarrett, program manager on reducing harmful fishing subsidies, Pew Charitable Trusts

In 2001, the WTO formally recognised the need to reform fishing subsidies and member nations four years later called for the abolition of incentives that contribute to overfishing. Negotiations languished for a decade but took on new urgency in 2015 after the UN adopted a set of 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDG). Among them was SDG 14.6, which calls for the prohibition by 2020 of subsidies that contribute to overcapacity, overfishing and illegal, unreported and unregulated (IUU) fishing.

Still, WTO’s last biennial meeting in December 2017 ended without an agreement on fishing subsidies. However, the 164 WTO member states, which must approve decisions by consensus, did agree to redouble efforts to reach an agreement by the end of 2019.

This year, negotiators have been meeting monthly at WTO headquarters in Geneva to try to break the stalemate. An agreement to ban fishing subsidies would have a profound impact on ocean health and national economies. Unlike other international agreements, such as the Paris accord on climate change, WTO actions are binding and carry the weight of law.

“The WTO is a body that really has teeth behind it, which makes negotiations hard and complicated,” said Isabel Jarrett, manager of the Pew Charitable Trusts program to reduce harmful fishing subsidies.

China has so far kept a low profile in the talks, according to observers, and has not publicly revealed its negotiating position. Yet a new proposal from China to cap fisheries subsidies, and a review of the country’s shifting policies, government reports and interviews with close followers of its fishing practices offer insights into how it might respond to a WTO agreement on subsidies and the impact on its fisheries.

“China is a leader in many ways on certain environmental issues and they have expressed their willingness to be part of other global environmental efforts, such as the Convention on Biological Diversity,” said Jarrett. “There’s a domestic policy in China to reduce fuel subsidies for domestic fishing and it’s important for China to take forward some of these commitments they have made domestically to the international stage.”

The making of a fishing superpower

From a few trawlers dispatched to fish off the coast of Africa in 1985, China’s overseas fleet has grown to 3,000 vessels (more than 2,400 of which were at sea in the first half of 2017, according to a United States government analysis). A report issued by China’s Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs in July 2016 noted that the country’s fishing fleet operated in the territorial waters of 40 countries as well as on the high seas in the Atlantic, Indian, Pacific and Southern oceans.

“More than 100 overseas representative offices and joint ventures were established, more than 30 overseas bases were built, and a number of processing logistics bases and trading markets were established in China,” stated the report celebrating the success of the 12th Five Year Plan (2011-2015) for its offshore fisheries.

Billions of dollars in subsidies fuelled that expansion. Tabitha Grace Mallory, an affiliate professor at the University of Washington who specialises in China fishing policy, calculated in a paper that the country spent 40.4 billion yuan (US$6.5 billion) on subsidies in 2013. About 94 per cent of those subsidies were for fuel, according to her study based on Chinese government reports and other Chinese sources.

Mallory is currently updating those numbers and has preliminarily estimated that fuel subsidies in 2016 fell to just under 8 billion yuan (US$1.2 billion). “That’s a huge decrease, which looks great,” said Mallory, who also serves as chief executive of the China Ocean Institute, a Seattle-based consultancy. “My suspicion, which is confirmed by conversations with experts in China, is that they’re definitely rolling back subsidies for the domestic fleet but a lot of subsidies will remain in place for the distant-water fleet.”

In response to a collapse of fish stocks in its territorial waters, China has imposed restrictions on its domestic fishing fleet, cracked down on illegal fishing and boosted aquaculture production. China’s State Ocean Administration reported that in the first nine months of 2017, captures of wild fish in domestic waters declined 11.9 per cent over the previous year while captures outside the country grew 14.2 per cent. China’s total wild fish captures declined 7.7 per cent in 2017.

Mallory says that statistics on China’s fishing industry are increasingly hard to obtain. “Since my 2016 paper, there’s been a huge decline in transparency in reporting on subsidies,” she said, noting China is far from alone in its secrecy about subsidies. “Maybe the increased scrutiny has caused them to pull back or maybe in the lead up to the WTO negotiations, there’s some hesitancy while they figure out what they’re doing.”

Adding to the confusion, Mallory says, is that China has combined data on subsidies that are beneficial—such as those that finance the decommissioning of boats to reduce fishing capacity—with those that are destructive, like payments for the renovation or construction of vessels. She said data from 2018 she has obtained shows that 59 per cent of those subsidies are going to China’s distant-water fishing fleet. “The data indicates that there is still a lot of support for distant-water fishing but it conflates disposal of vessels with construction,” Mallory said.

This story was originally published by chinadialogue Ocean under a Creative Commons’ License and was republished with permission.