First celebrated in 1970—the year that American troops invaded Cambodia, a cyclone claimed 500,000 lives in Bangladesh, and The Beatles broke up—today is the fiftieth Earth Day, a day that marked the beginning of the modern environmental movement.

To continue reading, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

Over the last 50 years, environmental protection measures have been rolled out all over the world, from the Clean Air, Clean Water and Endangered Species Acts in the United States, the birth place of Earth Day, to the Paris climate accord, which was signed on Earth Day 2016.

Despite the progress that environmentalism has made in parliaments and boardrooms, the world is under greater strain now than it was half a century ago—and this year could be the hardest yet. No single event of the last 50 years has had a bigger impact on our world than the ongoing coronavirus pandemic. Eco-Business examines how the virus is changing people and our planet.

Poverty exacerbated, inequality widening

It is a fallacy that the coronavirus is a leveller, impacting people of all socio-economic backgrounds in equal measure, the former chief executive of Unilever, Paul Polman, has pointed out. Many poor people cannot afford to self-isolate, particularly those working in the informal sector. In Bangladesh, the Philippines, India, Myanmar, Vietnam, Pakistan, Thailand and Indonesia, the majority of the workforce works informally, with no severance pay or sick leave if jobs are lost. Workers face a choice between going to work while sick, and going hungry. In Indonesia, where 60 per cent of the population works informally, the coronavirus death rate of 8 per cent is double the global average. In rich countries, too, the least advantaged are suffering the most and inequality in society is widening.

Cities, too dumb for pandemics

The design of cities, where 55 per cent of humanity lives, often in close quarters, has exposed their vulnerability to pandemics. “The “unthinkable” must be part of good urban design practice from now on,” comments Italian architect Patricia Viel. She said her country is paying the price for cities that lack the data and digital infrastructure to help governments assess, forecast and prevent viral spread. From now on, experts say that cities must be smartly retrofitted for social distancing, and as much retail as possible shift online. Public transport is likely to take a temporary hit, as citizens worry about the risk of infection in communal spaces. So will ride-sharing services, until assurances can be made about hygiene. The emergence of self-driving cars is likely to accelerate post-Covid, and cycling become more common. More people working from home will create more bustling residential areas, and neighbours helping one another through this crisis has shown the importance of social cohesion in city renewal.

Agriculture is going local

Discarded zucchini and squash on a farm in Florida. Image: Joe Raedle/Getty Images

Population control measures have disrupted food transport links, worries over food shortages have been followed by vast volumes of unsold produce, and farm labour has been in short supply in many countries, highlighting the value in local agriculture. Nowhere has this been demonstrated like China, the first country to be hit by the virus. Aided by e-commerce giants Alibaba and JD.com, consumer demand has been matched with farmer supply, closing the gap between urban markets and the growing regions, providing lessons for other countries in more resilient, sustainable food supply chains of the future. In Singapore, which imports 90 per cent of its food, attention has turned to vertical farming and the exploration of new forms of agriculture, such as growing rice at sea and harvesting microalgae as an alternative protein, to safeguard food security.

The viral threat of losing forests

Fire fighters tackle forest fires in Sumatra, Indonesia Image: Sipongi

Clearing forests is likely to increase the occurrence of diseases like Covid-19, as animals come into closer contact with people. In Indonesia, home to some of the world’s largest expanses of rainforest, some 8,000 hectares of forest have been lost so far this year. Agribusiness firms warn that the lockdown has made it more difficult to police and monitor deforestation on the ground outside their concessions, and slash-and-burn forestry has been reported in some areas. Syahrul Fitra, a researcher with green group Auriga, is also concerned that the government’s economic stimulus plans do not include assurances for the legal timber trade, which could fuel illegal logging. Meanwhile, as the media’s attention is focused on Covid-19, forest fires rage in northern Thailand.

Gender equality, locked down

The coronavirus, wrote Helen Lewis in an opinion piece in The Atlantic in March, will send many couples back to the 1950s. “Across the world, women’s independence will be a silent victim of the pandemic”, she said, pointing out that since women are generally paid less than men, they are more likely to do the unpaid care-giving work in locked-down households. Others have pointed out that this perspective undervalues unpaid labour, and reaffirms the corporate idea of what valuable work really means.

However, the most noticeable gender equality narrative to emerge from the time of Covid-19 is that female political leaders—which make up just 7 per cent of the world’s heads of state—have performed particularly well in navigating their countries through the crisis, with the likes of Taiwan President Tsai Ing-wen, New Zealand prime minister Jacinda Ardern and Germany’s chancellor Angela Merkel taking bold action to curb the virus.

The sharp rise of domestic violence

The most widespread but least reported human rights abuse—domestic violence—has reared its head as one quarter of the world’s population has gone into lockdown. Reported cases of domestic violence tripled in the two weeks after Jakarta went into lockdown, with similar spikes seen in Malaysia, Singapore and Australia. Social distancing measures have made it hard for victims to get shelter at women’s refuges. Health and financial worries combined with a desire among perpetrators to maintain a sense of power and control in their lives have prompted the increase in violence at home, research shows.

Racial discrimination is rising

Africans in China wear face masks. Image: Alex Plaveski/EPA/Shutterstock

Ever since the virus emerged from Wuhan, reports of racial discrimination against people of Chinese descent have been documented around the world, from Egypt to England. In Hong Kong, racial incidents have been reported against mainland Chinese and, in China, against people from Hubei, the province of which Wuhan is the capital. The World Health Organisation recommended that the virus be known as Covid-19 to avoid the disease being associated with its country of origin. But some political leaders, such as United States president Donald Trump, have persisted in referring to Covid-19 as “the Chinese virus”.

Meanwhile in China, reports have also emerged of racism against Africans, who are being blamed for Covid-19; people of African descent have been evicted from their homes, forced into quarantine, had visas cancelled and refused service in shops. African ambassadors to China have complained about what they regard as “the persistent harassment and humiliation of African nationals”.

Will personal freedom restrictions linger?

Not since World War II have governments taken such radical policy measures to curb the personal freedoms of their citizens. In locked-down China, public transport was stopped and drones deployed to police the mandatory wearing of face masks. In Dubai, citizens could not leave their homes at all, and were only permitted to go to a supermarket after booking an appointment through a government website. In Singapore, citizens are being encouraged to ‘snitch’ on one another to the authorities if they witness safe distancing violations. Human rights watchers worry that some of these measures could remain in place after lockdowns are lifted. Contract tracing apps are a particular cause for concern. These apps pose an “unprecedented” level of surveillance on citizens, commented privacy advocacy group Privacy International. “All of them must be temporary, necessary, and proportionate. When the pandemic is over, such extraordinary measures must be put to an end and held to account.”

The air is clearing—for now

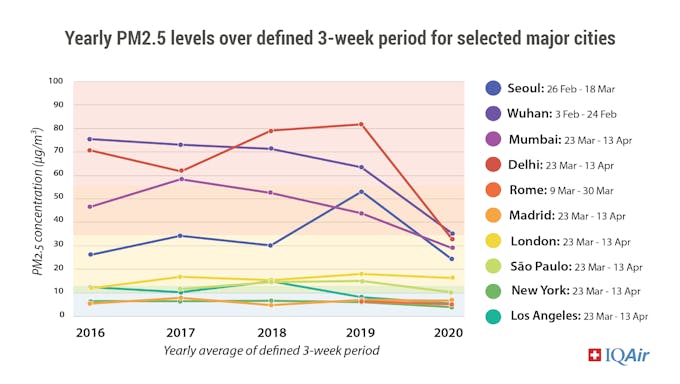

The impact of coronavirus lockdowns on air pollution (PM2.5 levels) in 10 major cities: Source: IQAir AirVisual

The closure of factories, easing of traffic and reduction in fossil fuel burning as humanity withdraws into quarantine has brought about dramatic reductions in air pollution, with the biggest reductions seen in the most polluted places. Greenhouse gas emissions in China, the world’s largest emitter, fell by almost one fifth between early February and mid-March as coal consumption and industrial output ebbed. But as China loosens lockdown measures and revives its economy, emissions are already rebounding. Experts worry that Covid-19 won’t reverse the trend of rising emissions globally, and as more economies emerge from lockdown and look to make up for lost time, the prospect of “revenge pollution” means that coronavirus won’t have helped the world to get any closer to climate targets.

Will renewables retreat?

Though less fossil fuels are burning, falling power consumption is not good news for renewable energy either. Disrupted supply chains for clean energy materials and a tanking global economy has made financing for renewables projects harder and investment less likely, prompting energy-watchers to slash forecasts for renewables. Meanwhile a low oil price worries observers that consumers will be less motivated to use energy efficiently and electric vehicles will lose their appeal.

A stick in the wheel of the circular economy

Face masks are ending up in the ocean.

Consumption has been hit hard by coronavirus. But in certain categories, such as groceries and personal hygiene, spending has grown as locked-down consumers opt for online deliveries. This has led to concerns that coronavirus has brought with it an increase in plastic pollution, as beaches and waterways become clogged with discarded disposable face masks. Plastic bags are also making a comeback as retailers rescind single-use bag bans and scrap bring-your-own-container schemes in fear they’ll help spread the disease. The revival of single-use plastic has been prompted by research from plastic industry-backed groups that claims the virus can survive on plastic for longer than on other surfaces. Meanwhile the low cost of oil has pushed up the price of recycled plastic, putting many recyclers out of business and threatening to derail corporate sustainable packaging commitments.

Water-scarce places reveal their vulnerability

Residents tussle over water in Chennai, India. Image: Tim Ha/Eco-Business

We are being advised by health authorities to wash our hands more frequently for at least 20 seconds to prevent outbreaks. But what about countries like Pakistan and India, where clean water is in short supply? Some 40 per cent of the world’s population lacks access to basic hand-washing facilities at home, and one billion people live in informal settlements, where overcrowding and lack of water access can fuel the spread of diseases like Covid-19. While aid agencies are helping water-stressed countries by installing portable hand-washing stations in public areas and other temporary measures, the pandemic has highlighted the urgent need for better water management to cope with future crises. Besides tripling investment in clean water access and sanitation, experts are stressing the need for greater protection of the ecosystems that safeguard water supplies.

Wildlife is reclaiming lost territory

Tales of dolphins and swans returning to the canals of Venice and elephants sauntering through a village in Yunnan, China turned out to be fake news as people clamoured for positive stories amid the terrifying Covid-19 media blizzard in March. But the return of animals to places where humans have retreated is really happening. Pumas have descended the Andes mountains into Santiago, Chile, wild boar have moved into central Barcelona, penguins have been seen waddling in the streets of Cape Town, and more turtles are laying their eggs on Thailand’s deserted beaches.

The pandemic has shown that nature can rebound at speed when given the chance. But coronavirus has also left wildlife vulnerable in some areas. Nine rhinos have been poached in South Africa since the start of the lockdown, and conservationists worry that their funding will be affected by a drop in tourism.

Scrutiny finally falls on the wildlife trade

An orphaned Asian palm civet at an animal rescue centre. Image: Robin Hicks/Eco-Business

Though conservationists worry that the ban on the US$74 billion wildlife trade in China—where the coronavirus is believed to have started—will not be permanent, and has loopholes allowing the trade in wild animals for medicine, fur and research, it’s a big step in the right direction for wildlife conservation. Could China take an unlikely lead in conserving endangered animals as its influence spreads elsewhere around Asia, the spine of the wildllife trade?

The best companies are revealing themselves. So are the worst

Regular outpourings of corporate communications in recent weeks have expressed how much companies “care” and how “committed” they are to help fight the coronavirus. Some have been genuine. Others not. Unlikely partnerships have formed between rivals in a range of industries, from pharmaceuticals to tech, to combat the pandemic, pointing to a future where cross-sector collaboration is more common. But the virus has also prompted companies in the aviation, timber, agriculture, fossil fuels, and automotive industries to seek to weaken and delay environmental protection measures while soliciting governments for stimulus packages. Environmental campaigners such as Mighty Earth have called companies doing this “coronavirus profiteers”.