As climate change disrupts the Arctic, a myriad of changes are predicted that will affect everywhere on Earth, even countries that have historically been sheltered from the wrath of nature, such as Singapore, as the melting polar ice raises sea levels.

To continue reading, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

Yet the changing Arctic landscape presents many Asian nations with opportunities to benefit from its wealth of natural resources.

Mikaa Mered, professor at the Free Institute of International Relations Studies (ILERI) pointed out at a recent event in Singapore that mining and oil and gas exploration have been ongoing in the Arctic for more than a hundred years, but what’s new is “the magnitude of potential” that the region holds for development in the future.

A recurring view during the event, called Connecting the Arctic & Asia through Climate Actions and Sustainable Development and held at the French Embassy, was that as the Arctic ice sheets disappear, trade routes connecting northern nations become increasingly feasible.

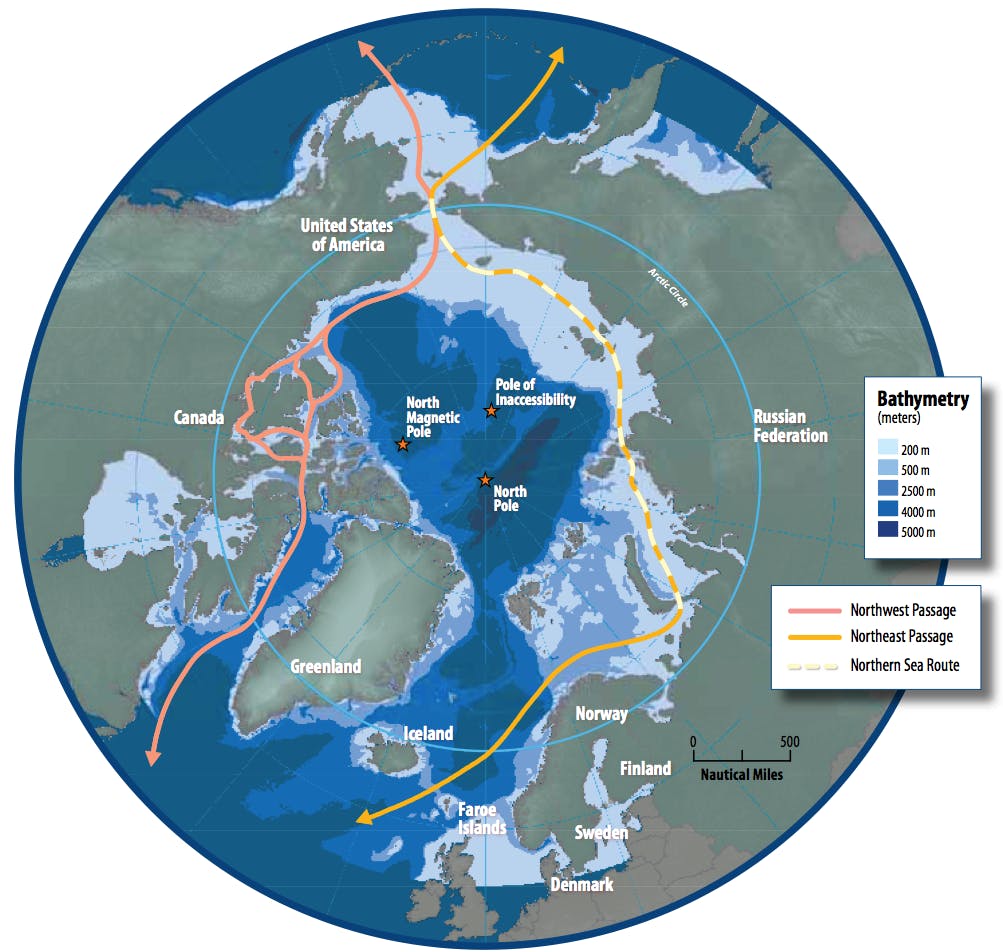

The opening of sea routes north of Russia will reduce the distance between the east-west route that passes through the Suez Canal by 40 per cent. And shipping times from Europe, through Eurasia, to Asia will be reduced by nine to 13 days, and save 40 per cent of the shipping cost.

Some have suggested that the melting ice threatens shipping ports such as Singapore, since vessels heading from Europe to north-east Asia will be able skip the city-state and sail directly to China, Japan and South Korea. But experts have suggested that Singapore will not be significantly affected, and will benefit from new business opportunities in ship building, developing ports and other infrastructure technology as the region opens up.

“The Arctic is globalising”, Mered said. While countries in the Arctic circle—which include United States, Canada, Russia, Finland, and Sweden—jostle for geo-political influence over the region, Asian nations like Japan, Singapore and China seek to exploit the region for economic reasons, he noted.

Nations with access to the Arctic sea will be able to shorten their sea transport routes because of the melting ice. Image: Arctic Council via Wikimedia Commons

The cost of opportunity

But development in the Arctic brings with it costs. Dr Philip Andrews-Speed, senior principal fellow at the Energy Study Institute, National University of Singapore, warned that the degrading quality of Arctic ice and the melting of the permafrost is predicted to create a positive feedback loop that will increase the rate of rising sea levels as the global temperature increases. The irony is that, although reductions in sea ice will provide better access to northern sea routes, the melting permafrost will make transport on land more difficult.

“Our connection with the Arctic is not just material, it is biological,” said Philips, referring to the sharp decline in biodiversity predicted in the Arctic as a result of the landscape’s changing topography. Pollution is also a problem that threatens the region’s iconic species, such the Polar bear, Arctic fox, Prairie pigeon, and Narwhal.

“Despite many challenges, development in the Arctic will continue whether you want to save it or not. What really matters is whether we will see business as usual or new practices emerge. That’s the big question,” Mikaa Mered said. The development of renewable energy in the polar regions was one way to enable economic growth and offer an alternative to fossil fuel extraction, he said.

Mered added that territories like Iceland, Russia, and Alaska have great potential for geothermal, wood/biomass, and wind energy, respectively, and should be urged to develop sources of clean energy. A similar view was expressed by Dr Philip: “Energy is the big thing, which is why energy strategies are key to dealing with this [climate risk] problem in most countries.”

The biggest barrier to sustainable development in the Arctic is making alternative low-carbon practices economically competitive, and progressively cheaper, in a fossil fuel- dominated market, said Mered. He told Eco-Business that to compete with the conventional industries, economic and policy incentives were needed to boost renewables.

But fighting climate change isn’t the only challenge. Resilience needs to be built against climate risks, Mered said. Equally important, he added, are the partnerships between private and public institutions to remove barriers to achieving sustainable development in the Arctic.