It is, at times, hard to follow Jacqui Hocking’s story as she relates how she survived burnout.

To continue reading, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

The Melbourne-born, Singapore-based social entrepreneur’s storyline jumps back and forth in time as she chronicles more than three decades of restlessly trying to make good things happen.

“Good luck writing this,” she tells Eco-Business as she dives down and up a series of rabbit holes – living with ADHD, surviving Covid, quitting alcohol, running a startup, and much else – to narrate and unpack the life journey of a person who has already probably done more at the age of 33 than most of us could accomplish in three lifetimes.

Listing just a few of Hocking’s life milestones is exhausting.

Founded a film company as a teenager. Left school, sailed around the world on a yacht documenting the effects of climate change. Co-founded a sustainability consulting and media production firm. Birthed another company. Launched a film festival. Founded another consultancy during Covid. Sold her company to a public relations firm.

Interspersed with that list are projects for floating hospitals in Papua New Guinea, solar fields in Tanzania, circular economy solutions in Indonesia and India, and carbon offsets in the Amazon.

People who know Jacqui Hocking describe her as a very giving person. A tirelessly positive, energetic individual. A “super-connector” who seems to be everywhere at once, building relationships, getting things done.

But her relentless drive has come at a personal cost – burnout.

“

I was my work. I’d become unhuman. I didn’t acknowledge that I needed to eat, sleep, have friends or a relationship.

Burnout was recognised as an occupational phenomenon by the World Health Organization in 2019. People who burn out typically feel like they’re drowning; exhausted, detached and unable to cope.

The condition was coined in the 1970s to describe people struggling in “helping” professions such as medicine and healthcare. But burnout nowadays refers to anyone who is chronically overworked.

Sustainability professionals, who are inclined to throw themselves into their jobs for a good cause, are particularly susceptible to burnout.

Hocking is, perhaps, more vulnerable than most because of the way her brain is wired. People who know her may not be surprised to learn that she has a condition characterised by restlessness and hyperactivity that may have contributed to her burning out.

At the end of 2022, she was diagnosed with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), a condition she long suspected she had, which is chronically underdiagnosed in women. “Off the charts,” she says, referring to the severity of her condition.

Many entrepreneurs have similar, related symptoms, she says. “Perfectionism, risk-taking and novelty-seeking – it’s all connected to the same type of drive to make things happen, and is a recipe for burnout,” Hocking explains.

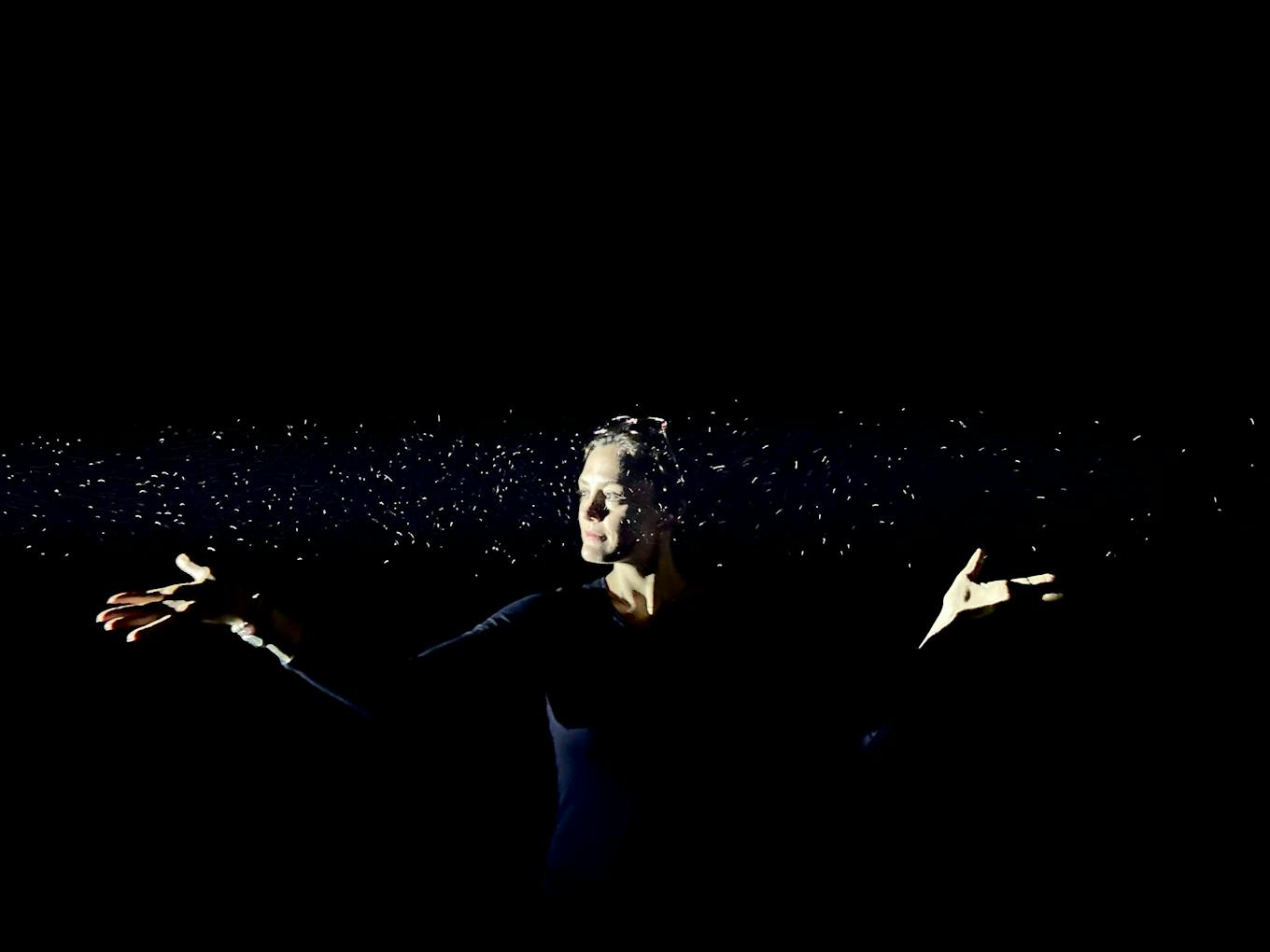

Jacqui Hocking in an exhibit visualising particulate matter by Argentine contemporary artist Tomás Saraceno at MONA art gallery in Tasmania. Hocking is a glass-half-full sort of person. “I’m far too optimistic, stubbornly so – and that can make me hard to work with,” she says. Image: Jacqui Hocking

Slow burn

For Hocking, burnout has been a slow burn, a mental health tightrope she has walked for almost a decade.

It began in 2015, the year before she left Gone Adventurin’, the company she had co-founded five years prior, and peaked dangerously during the Covid-19 pandemic, when the future of her current company, VS Story, looked in serious doubt.

Clients were not buying into the consulting side of the Gone Adventurin’ offering – to build sustainability into their business strategies – and that was a big drain on her. “We were trying to build purpose into businesses. But we kept being pushed to the marketing or CSR department. I guess we were 10 years too early,” she says.

Losing good corporate clients was disillusioning. She would build relationships with business people “who got it”, only for them to leave for more “purposeful” jobs in NGOs or startups.

“Systems change can only come about by working with big actors, like multinationals, through their supply chains. To see good people leave these companies was hard.”

But harder times were to come. One day in 2016, she found herself without a job or an employment pass. “[The co-directors] announced they were going in a different direction, and I wasn’t part of it,” she recalls.

She had to dust herself off, find new business partners, and start again. “Even the thought of having to do that again freaks me out.”

She survived that period by finding people who’d been on the same rollercoaster. “Meeting other entrepreneurs made me feel like I wasn’t insane. I’ve always been terrified that I’m crazy.”

The Covid crunch

She kept going. Her new business, VS Story, took off. Then Covid hit.

“I remember the end of 2019 and thinking, ‘We’ve got it. All the scrappy startup stuff is over. It’s all going to be good from here.’” But in the space of just two weeks, 80 per cent of her business evaporated.

She decided not to let any of her staff go, even if her company ran out of money.

Her company didn’t go under. The opposite happened, which brought a different kind of pressure.

“For years, we had been busting a gut to get stories out, get people listening. And for whatever reason, in 2020 people started to listen. Suddenly there was so much to do. It was too much.”

As a young female entrepreneur, I’ve always struggled with imposter syndrome.

In the first year of the pandemic, Hocking says if she had not made make radical changes to the way she had been living, she wouldn’t have survived.

“I was not eating or sleeping. I was always running somewhere.”

“I used to say that if there was a pill for sleeping and eating, I’d take it. I didn’t want to miss out on anything.”

She was working all hours. “I was my work. I’d become unhuman. I didn’t acknowledge that I needed to eat, sleep, have friends or a relationship.”

She worried that her punishing work ethic was affecting her team. “If you are a workaholic, your team will become workaholics around you,” she says.

It is a myth that workaholism is productive, Hocking says. “If you’re addicted to exercise, eventually you’ll get injured. Compulsive behaviour of any kind is bad.”

She was also drinking a lot and was depressed. Suicidal thoughts had started to creep in. The panic attacks that she had starting having when she was 2018 became unmanageable.

“I wasn’t panicking because of my health. I was worried that I couldn’t work anymore,” she says. “I was worried that the B Corp dream – that companies can be a force for good – was slipping away.”

Jacqui Hocking is Southeast Asia ambassador for B Corp, an organisation that promotes low-impact business. “I’m far too optimistic, stubbornly so – and that can make me hard to work with,” says Hocking. “Unrealistic expectations are not healthy for anybody, because you expose yourself to disappointment.” Image: Jacqui Hocking

Recovery

Something had to give. So she changed gear and started to focus on herself.

She tried meditation, yoga, “all the woo-woo stuff”. But that didn’t work. Sitting still to meditate is particularly difficult for people with ADHD.

So she started reading about neurology to learn more about how her brain works. She wanted to understand why she was feeling the way she was.

She devoured all the books she could get her hands on about the mind, entrepreneurship and recovery.

How to Do the Work by Nicole LePera. Divergent Mind by Jenara Nerenberg. Quit Like a woman by Holly Whitaker. Option B by Sheryl Sandberg. Scar Tissue by Anthony Kiedis. The Gift of Intensity by Imi Lo. This Naked Mind by Annie Grace. Woman of Substances by Jenny Valentish.

She worked hard to intentionally make her life easier. Religiously making lists was one of many fixes. “It may sound stupid, but if it’s not my calendar it does not exist,” she says.

Hocking also did a lot of research on the alcohol industry. Looking behind the curtain of the trade helped her to stop drinking completely.

“Alcohol is glorified by almost every industry. It is a requirement in some,” she says, sipping a tonic water in a bar in Singapore’s Chinatown.

The idea that business deals get done over whisky, and women can become part of the boys club by drinking, is dangerous, she says.

“It’s an addictive, deadly substance – particularly for women,” she says. “We should never have work events that revolve around a drug.”

Though she was a not a particularly heavy drinker, she was still drinking to excess once or twice a week.

“

The best business tip I’ve ever learned is the understanding that nobody is going to save the world on their own.

“My drinking was accepted as normal by everyone around me. Which is messed up,” she says. “People feel pressured to drink and are drinking far too much.”

Hocking had been using alcohol as a crutch.

“As a young female entrepreneur, I’ve always struggled with imposter syndrome. You have to have an insane amount of confidence to run a company or convince CEOs twice your age to run a sustainable business. Alcohol gave me confidence.”

But it wasn’t alcohol that inspired Hocking to run events like the Singapore Eco Film Festival, be a B Corp ambassador and evangelise about responsible business. It was, she says, a sense of duty to represent women in the sector.

“Not enough women step up. If you believe in gender equality you should be public speaking more or asking for a raise. It’s your responsibility to show women what is possible,” she says.

As an introvert, Hocking does not find putting her head above the parapet easy. But doing so without alcohol has been an important milestone in her life. She hasn’t touched a drop since April 2021.

“The best piece of advice I’ve ever heard for female business owners? Don’t drink.”

Growing

Hocking now dedicates an hour to her health and wellbeing every morning before she starts work.

One of the first things she does is write a gratitude list – things she’s thankful for. She sends the list to a friend or family member to keep herself accountable.

“Gratitude gives you perspective,” Hocking says. “In the environmental space, we get so stuck into what we’re doing that we forget about the privilege of having clean drinking water.”

She also spends the early morning with her pets – two guinea pigs and terrapin – waters her plants, and makes her bed.

“I take care of my home. That’s so important. I do one thing to make home better every day,” she says.

Then she has breakfast. Her husband, Flo, who is French, taught her to fall in love with food.

“Flo is a big reason I’m ok now. Food is not just fuel, it’s an experience to be shared with another person. It’s a connection. He taught me that.”

Until recently, she medicated. “People say you shouldn’t take antidepressants because it takes away your experience of life. That is wrong. If you’re depressed, antidepressants give you the ability to live life – for you to be you.”

She has taken Lexapro, which is used to treat depression and anxiety. “God loves me, this is so, for He gave me Lexapro,” she chirps, reciting a popular phrase among depressives taken from Glennan Doyle’s Untamed.

“It tempers extremes. Depressives can feel so low that they can’t get out of bed and want to kill everybody, or so happy that they want to quit their job immediately and move to Jamaica.”

Since December, after she was diagnosed with ADHD, she has been able to manage her symptoms better, so has stopped taking medication.

Jacqui Hocking speaking about systems entrepreneurship at TEDx in Singapore. “Not enough women step up. If you believe in gender equality you should be public speaking more or asking for a raise. It’s your responsibility to show women what is possible,” she says. Image: Jacqui Hocking

Finding balance

Hocking still works intensely, but has learned to balance work with other things.

“I still pull all-nighters sometimes. But work is no longer my identity,” she says.

“I don’t believe it is possible to stop being an addict if you have an addictive personality. That drive will never leave you. But being aware of it helps to control it,” she says.

She is now able to mentally recognise that work is not the be-all and end-all, even for an agitator who desperately wants to effect change.

Key to the ability to let go of work has been learning humility. Entrepreneurs, Hocking says, often succumb to the idea that they’re always right and are led by their egos.

And while a certain amount of ego is necessary for people to pursue their ambitions, Hocking says sustainability practitioners need to remember that “it’s not only about you”.

“The best business tip I’ve ever learned is the understanding that nobody is going to save the world on their own,” she says. “I am nothing without my team.”

She now invests a lot more time in her staff to ensure they feel valued and respected, and has taken management advice from the book Radical Candor by Kim Scott.

Scott’s philosophy is that business leaders can be effective managers by showing that they care about their staff, but also challenging them directly without being aggressive or insincere.

“That book changed my life. You can care a lot about everyone on your team, but as a leader if you don’t challenge your people, you just become manipulative,” Hocking says.

Advice for younger self

Building genuine self-confidence is one of the things that Hocking would wish for her younger self – and for other young people entering the sustainability world who are as impatient as her to make a difference.

“Learn about what you want to do. Really look at yourself and find out what drives you. And know that your energy is actually a gift,” she says, referring to how she has come to terms with her ADHD.

Despite working hard to change the way she lives to beat burnout, a big lesson for Hocking over the past few years is self acceptance.

“Don’t be ashamed of who you are. Embrace it. I’ve spent my entire life trying to ‘fix’ me. But I don’t really need to. I’m totally fine being weird. I survived.”

“Some people won’t like you. I spent my whole life trying to make everyone love me. It’s not going to happen. You cannot be everyone’s friend,” she says.

Above all, Hocking urges young people to never forget that anything is possible, but also never lose sight of healthy boundaries for ambition.

“Everyone will tell you that you’re insane. But you have to believe you can do it,” she says. “You also need to be able to take care of yourself, otherwise you will burn out or lose confidence.”

“The secret is surrounding yourself with people who believe in you. Do not let yourself swim alone.”