Experts familiar with the inner workings of how a new long-term strategy for India’s net-zero targets was drafted are defending the plan as a clear articulation of India’s intention for low-carbon development, with sectoral plans laid out.

To continue reading, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

This is amid some criticism from civil society that the broad-brush plans lack teeth. The national report, released on Monday at the United Nations COP27 climate summit in Egypt, zeroes in on how India, the world’s fastest-growing major economy and second-largest consumer of coal, will decarbonise six key sectors of the economy. These are electricity, transport, urbanisation, industry, carbon removal and forests.

The strategy for the first time sketches out how India will meet its decarbonisation pledge made in 2021 to achieve net-zero emissions by 2070. Its environment minister Bhupender Yadav, speaking at a COP27 event marking the report’s launch, described it as an important milestone.

Navroz Dubash, professor at New Delhi-based think tank Centre for Policy Research, an organisation involved in drafting the document, told Eco-Business that the strategy should be viewed as a “living document” that will serve as a base for future iterations of India’s plans, when asked why India made no indication of when it aims to peak carbon emissions, nor set out new or interim decarbonisation targets in its plan.

India’s minister for environment, forest and climate change Bhupender Yadav (left) partcipating in a ministerial meet with his counterparts from Brazil, South Africa and China on the sidelines of COP27 in Egypt. Image: Bhupender Yadav / Twitter

Dubash explained that India could seek to outline more specific targets in the future, including by using quantitative modelling methods. The strategy announced November 14 will still make for a “system transformation”, as it includes sectors that thus far do not have long-term goals for decarbonisation, such as transport. It will provide clarity to the bureaucracy as well as to the private sector, he added.

Under the landmark agreement, all countries are required to submit a strategy document to the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) showing how they will help combat global warming. These plans are known as a Long-Term Low Emissions and Development Strategies (LT-LEDS).

Despite a 2020 deadline for the plans, just 56 countries have so far submitted one. India is the last of the world’s five largest economies to do so.

Sectoral mitigation plans missing agriculture

Ulka Kelkar, director of the climate programme at research think tank WRI India, believes the strategy will play an important role in bringing together different ministries overseeing various sectors of the economy and provides an opportunity for better coordination.

“Going forward, India will need detailed sectoral roadmaps and milestones, along with its net-zero targets, and avoid investments that are incompatible with a low-emissions and climate-resilient future,” she said.

She specifically highlights a section in the report on adaptation and resilience which reiterates India’s calls for climate finance and technology transfer from rich countries. Loss and damage has been a recurring topic at this year’s COP27 summit. Negotiations on how the developed world should help pay for climate change-related devastation in vulnerable regions are now formally on the COP agenda.

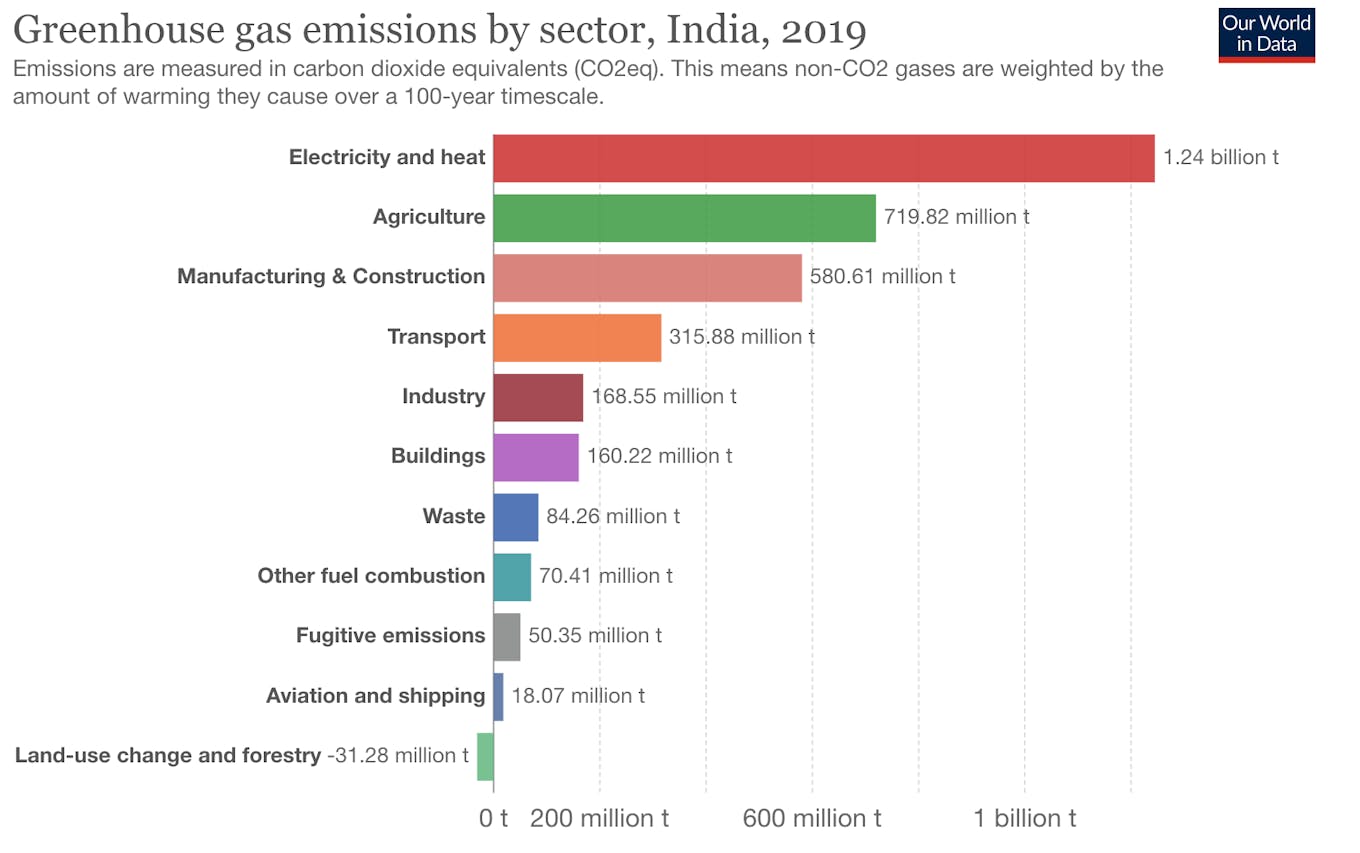

Among the new sectoral decarbonisation plans, agriculture has been omitted. The sector emitted more greenhouse gases (GHGs) than India’s transport and industry combined, according to 2019 statistics.

Source: Our World in Data based on Climate Analysis Indicators Tool (CAIT)

Kelkar said that there are still opportunities for India to reduce methane emissions from agriculture, by improving feed use, as well as reduce water usage. She added that a policy-led shift towards planting less water-intensive millets rather than paddy, can significantly reduce agricultural emissions.

India has consistently maintained that the methane emissions from the two highest emitting activities in the Indian farm sector – enteric fermentation in cattle stomachs and paddy cultivation – are “survival” emissions of small farmers and not “luxury” emissions. Agriculture has historically been left out of India’s international commitments for climate action. The sector was also not included when India made pre-2020 voluntary commitments for emission intensity targets.

Nuclear and coal

India’s energy plans laid out under the long-term strategy also include a push for nuclear – a three-fold increase from the current 7 GW of installed capacity – as well as for green hydrogen, fuel cells and biofuels, in addition to solar and wind. It emphasises that while the share of coal in installed capacity and supply of power will decline, coal will be needed for grid stabilisation and to guarantee India’s energy security.

“[The] key factors will be the price reduction trajectory of electricity storage systems and financial support and technology transfer from developed countries,” the document said about reducing India’s reliance on coal.

The strategy calls for more research into emerging technologies including coal gasification, carbon capture, utilisation and storage systems, biomass co-firing and beneficiation technologies, among others, and emphasises that India’s per capita coal consumption in 2019 was only half the world average. “Thus, it is inconsistent to focus disproportionally on lower coal use instead of lower total emissions,” it added.

“India was likely to peak coal before the end of this decade and many studies in fact highlight that it can be achieved by 2025,” said Vibhuti Garg, director for South Asia at the think tank IEEFA, “But the Russia-Ukraine War and the increasing price of renewable energy and energy storage have shifted the timelines.”

At this juncture, energy security and economic growth are the main concerns of the government, so it is unlikely to announce a coal peak. “But there is urgency and all efforts towards energy transition need to accelerate. India should be looking at stabilising the situation at home and should announce a coal peak in the near future,” said Garg.