At a four-day meeting in Istanbul last week, delegates debated several different approaches for the work programme of the IPCC’s seventh assessment cycle.

These included a more radical option to replace its huge assessment report with a series of shorter special reports on specific topics.

Nonetheless, delegates decided in favour of the usual assessment report and instead focused on the possibility of its three working group reports being delivered by the end of 2028.

This would allow the reports to inform the UN’s second global stocktake, which will gauge progress towards the Paris Agreement goals.

However, despite most governments agreeing on the accelerated timetable, a few countries “strenuously objected”, blocking a final decision on timelines, which will be revisited at an IPCC meeting in the summer.

One person present at the meeting tells Carbon Brief that “most of the resistance about the 2028 timeline came from Saudi Arabia, China and India”.

IPCC chair Prof Jim Skea described the gathering of more than 375 delegates from 120 governments – which overran into a fifth day – as the “one of the most intense meetings” he had ever experienced.

The seventh assessment cycle will also include a special report on climate change and cities as well as a methodology report on short-lived climate forcers – decisions that governments had previously already agreed.

The deliberations saw the addition of a second methodology report on carbon dioxide removal technologies, carbon capture utilisation and storage, plus a revision to the IPCC’s 1994 technical guidelines on impacts and adaptation. An overall “synthesis” report for AR7 will follow in 2029.

Reacting to the decisions, one scientist tells Carbon Brief that she is “not thrilled” by the decision to produce “a whole set of working group reports again”, given they will “not say that much new”.

“

There is a bewildering range of frameworks being suggested and applied to track and monitor adaptation progress, and the policy salience is pressing, with discussions for the global goal on adaptation ongoing.

Dr Chandni Singh, senior researcher, Indian Institute for Human Settlements

And another says that “waiting until 2028 for the three reports and 2029 for the synthesis is too late to have an impact on decision-making. The world will be significantly different by then”.

What was the purpose of the meeting?

The synthesis report, published in March 2023, marked the final product of the IPCC’s sixth assessment report (AR6) cycle.

Just weeks after its publication, the secretary of the IPCC invited member countries to submit nominations for the IPCC bureau for the AR7 cycle. Over the following months, 100 nominations were submitted for 34 positions – including IPCC chair, vice chairs and co-chairs and working group vice chairs.

Four candidates were nominated for the position of IPCC chair – Dr Debra Roberts from South Africa, Dr Thelma Krug from Brazil, Prof Jean-Pascal Van Ypersele from Belgium and Prof Jim Skea from the UK. These were the first elections in the history of the IPCC with women running for the position of chair.

The new IPCC chair and leadership team were elected at a meeting in Nairobi, Kenya, in July last year, via a secret ballot.

Prof Jim Skea was elected as chair, as the IPCC announced:

“With nearly 40 years of climate science experience and expertise, Jim Skea will lead the IPCC through its seventh assessment cycle. Skea was elected by 90 votes to 69 in a run-off with Thelma Krug.”

To select the rest of the bureau, the IPCC mandates that at least one IPCC vice chair and one co-chair from each working group should be from a developing country.

Dr Ladislaus Chang’a from Tanzania, Prof Ramón Pichs-Madruga from Cuba and Prof Diana Ürge-Vorsatz from Hungary were elected to the positions of IPCC vice chair.

IPCC documentation adds that “consideration should also be given to promoting gender balance”. Women make up 40% of the IPCC bureau for AR7 (pdf).

The meeting in Turkey was the first full meeting for the new leadership team. Its purpose was to make a series of decisions for AR7, such as discussing the IPCC budget over 2023-26 and reviewing lessons learned from AR6.

Skea also presented his “vision for the seventh assessment cycle”, in which he highlighted three key themes – policy relevance, inclusivity and interdisciplinarity.

For example, on interdisciplinarity, Skea said that he is “keen to explore ways of enhancing collaboration” with the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES), given the “intertwined nature of the climate, biodiversity and pollution challenges”.

What decisions were delegates making?

Among all the decisions that government delegates debated last week, the one that dominated discussions was which option to choose for AR7’s “programme of work”.

This programme sets out the overall approach that the IPCC takes through the assessment cycle, including the number and types of reports that the body produces.

Traditionally, the centrepiece of an IPCC cycle is an “assessment report” that comprises three working group reports and an overall “synthesis” report. The IPCC’s three working groups are:

- Working Group I (WG1): The physical science basis

- Working Group II (WG2): Impacts, adaptation and vulnerability

- Working Group III (WG3): Mitigation of climate change

For AR6, these reports were published in August 2021, February 2022 and April 2022, respectively. They were each around 2,000-3,000 pages in length.

The synthesis report then “integrates” the main findings of the three working group reports. It also takes into account any “special reports” that the IPCC has published during the assessment cycle.

These are shorter reports on specific topics, written by authors from across the three working groups. In AR6, for example, the IPCC published three special reports – each around 600-900 pages long:

- Global warming of 1.5°C (“SR15”) in October 2018

- Climate change and land (“SRCCL”) in August 2019

- The ocean and cryosphere in a changing climate (“SROCC”) in September 2019

Finally, an assessment cycle typically also includes “methodology” reports, which “provide practical guidelines for the preparation of greenhouse gas inventories” and “technical papers”, which are “prepared on topics for which an objective international scientific/technical perspective is essential”.

Ahead of the meeting in Turkey, an “informal group on the programme of work” had been established to prepare a paper setting out the options for the AR7 programme of work, taking into account the lessons learned from AR6 and the views of IPCC member countries. (Of the IPCC’s 195 members, 66 sent in submissions – roughly split 60-40 between developing and developed countries.)

One of the challenges faced during AR6 was the “very high workload” as a result of “the unprecedented number of reports, the rapidly increasing literature, and a significant increase of review comments on the final government draft [of the reports]”, the paper says.

It notes the need for IPCC reports to be “shorter and more concise, focused on new science and [able to] provide policy relevant information”.

The paper adds that “many member countries recommended ensuring adequate input from the IPCC is available for the second global stocktake to be concluded in 2028, either as a contribution from the assessment reports, topical [special reports], or as a specific dedicated product”.

The global stocktake is a five-yearly temperature check that is a vital part of the Paris Agreement. It is meant to help countries collectively assess where they are, where they want to go and how to get there in terms of climate action and to identify gaps to course correct.

In the text of the first global stocktake, agreed at the UN COP28 summit in Dubai last year, governments invited the IPCC to “consider how best to align its work with the second and subsequent global stocktakes” and also “to provide relevant and timely information for the next global stocktake”.

What was agreed for the AR7 ‘programme of work’?

The informal group set out three options for AR7’s programme of work:

- A “light” option with the usual assessment report and then just one special report and methodology report. This would see a “reduced workload compared to the AR6” and a shorter timeline.

- A “classical” option with the usual assessment report and up to two special reports and two methodology reports.

- A “special report gallery” option that replaces the assessment report with a larger collection of special reports (a working assumption of four).

The paper notes that “nearly all” member countries wanted AR7 to include the three working groups reports and synthesis, and the “vast majority” were also in favour of more than one special report and methodology report. (There were 13 countries that wanted to stick with one special report and methodology report.)

Previous assessment cycles suggest that a single working group report takes four years to produce from start to finish, the paper notes, while a special or methodology report can take three or three-and-a-half years. Although working group reports within an assessment cycle are produced in parallel, a complete set – including a synthesis report – ”is not considered possible in less than about four and a half years”, the paper says.

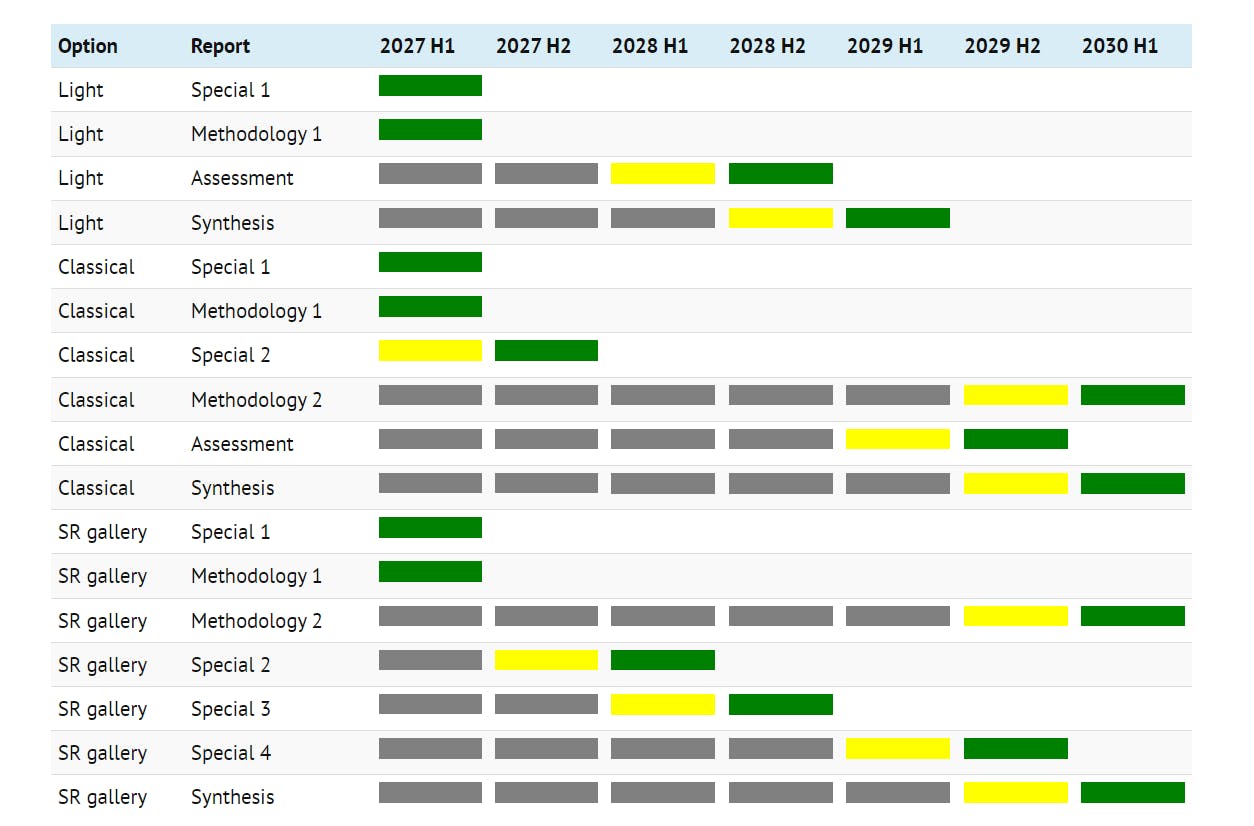

The table below, from the paper, presents the feasibility of when the reports could be published under each of the three options – from “not feasible” (grey) to “risk of delay” (yellow) and “feasible” (green).

Feasibility of release of the products listed in the AR7 structure options at indicated periods in time, based on past practice, from “not feasible” (grey) to “risk of delay” (yellow) and “feasible” (green). Source: IPCC (2024)

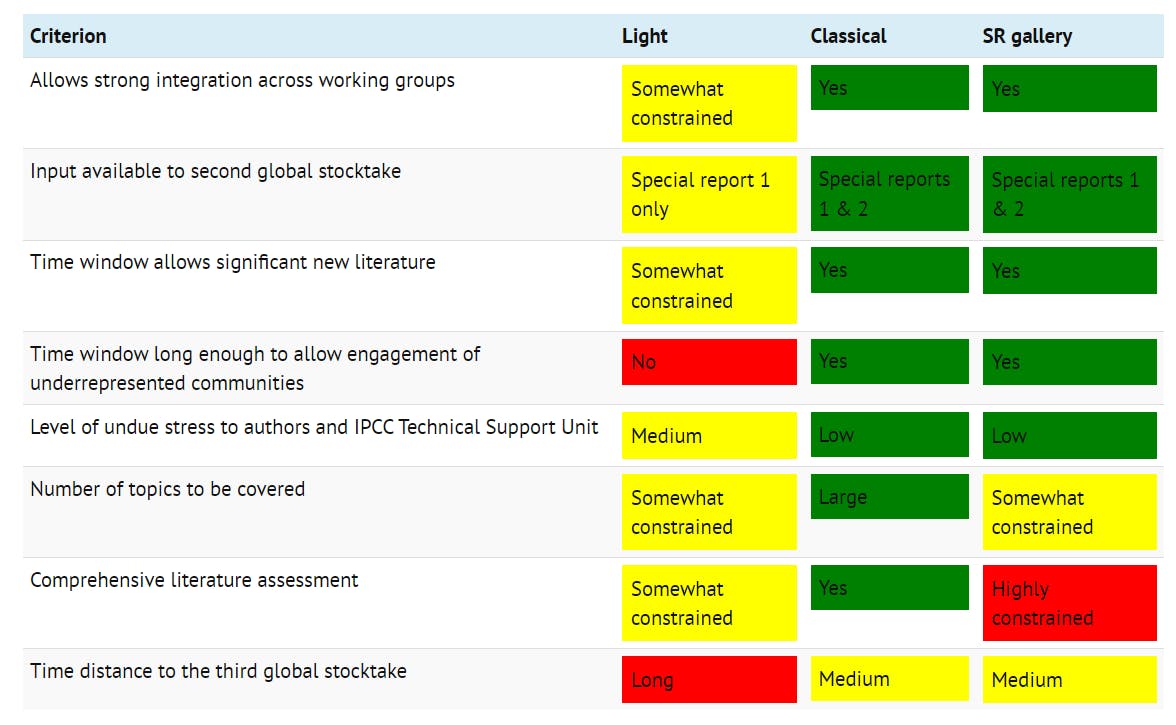

The paper analysed the three options against a series of criteria that include the time allowed for “engagement of underrepresented communities”. The findings, shown in the “scorecard” below, classify how achievable each criterion is for the three options – yes (green), no (red) or partly (yellow).

Scorecard for the three programme options assessed against a series of criteria. Shading refers to whether that criterion is achievable - yes (green), no (red) or partly (yellow). Source: IPCC (2024)

Despite being a “fairly straightforward exercise in agenda setting”, the discussions over these options at the IPCC meeting in Turkey “evolved into fraught deliberations that ran overnight on Friday and well into Saturday morning”, the Earth Negotiations Bulletin (ENB) reports.

It adds that the discussions “came down to the wire as delegates laboured in plenary and huddles to secure consensus on the programme of work”.

The final decision falls between the “light” and “classical” options – comprising a full assessment report with synthesis, as well as one special report and two methodology reports. In addition, AR7 will also include a revision of the IPCC’s technical guidelines on impacts and adaptation, published way back in 1994. (See following sections for more details.)

Skea tells Carbon Brief that the “big issue in the mind of most governments when they went into the meeting” was for “the IPCC to produce something that’s useful for the global stocktake by the end of 2028”. (Even though this process actually starts “in late 2026 through 2027”, he notes.)

There were “kind of two ways of going about” this, explains Skea:

“One was to have a second special report, which was prepared in time for the global stocktake with the working group reports coming after that – and, obviously, not being ready in time. The second option was to dispense with the second special report and produce the three working group reports on quite a fast timetable.”

Therefore, says Skea, “what we’ve ended up with is much more like what was labelled ‘light’, because the key point of ‘light’ is that there were no extra products before the second global stocktake”. (The agreed second methodology report “could take place later” in the assessment cycle, Skea notes.)

However, while there was agreement on the selection of reports, the “accelerated” timeline for working group reports was not agreed as “some countries didn’t necessarily want that”, he adds.

Prof Sonia Seneviratne, a climate scientist from ETH Zurich who is a WG1 vice-chair for AR7, notes that “it was very difficult to reach a final decision because a majority of countries wanted to have all assessment reports completed at the latest in 2028”. She tells Carbon Brief:

“Delivery of the IPCC [assessment] report in 2028 would be critical for the IPCC to fulfil its mandate of being ‘policy relevant’. [Nonetheless,] the final decision keeps the door open for the three assessment reports to be released by 2028 – that is, in time for the global stocktake – provided that the schedule is carefully developed.”

Prof Friederike Otto, senior lecturer in climate science at Imperial College London’s Grantham Institute and IPCC AR6 author, says she is “not thrilled” by the decision to produce “a whole set of working group reports again”, which “will require a huge amount of work for many scientists”.

The final reports for WG1 and WG3 will especially “not say that much new”, she tells Carbon Brief, costing the “best scientists…a lot of time they cannot use to actually advance the pressing questions”.

Dr Valérie Masson-Delmotte, a senior researcher at the Laboratoire des Science du Climat et de l’environnement in France and IPCC WG1 co-chair during AR6, says that the “positive” of not adding further special reports “is that there will be more time for expert meetings or workshops in particular on topics possibly stimulating the integration across working groups”.

However, she tells Carbon Brief:

“The less positive outcome is a lack of innovation for the AR7, which I see as a transition cycle, and where I think it is critical to prepare a different approach for the AR8 in order to keep IPCC policy relevant and motivating for scientists.”

This timeline (see section below) means that, even with only one special report, the AR7 cycle “might be much more challenging” than AR6, says Prof Joeri Rogelj, professor of climate science and policy at Imperial College London and IPCC AR6 author. He tells Carbon Brief that “this looks like a daunting cycle”, adding:

“Given the sequence of working group reports and the time needed to finalise, review and approve reports, this puts enormous time pressure on WG1 and WG2.”

How many special reports will AR7 have?

The decision to limit the production of new special reports is in line with the reported preferences of IPCC chair Jim Skea, who previously promised that he would strongly resist pressure to produce more reports, saying they dragged on the IPCC’s core work and resources.

“I’ll say something very strongly – over my dead body will we see lots and lots of special reports,” Skea said shortly after he was elected.

At its 43rd session in April 2016, the IPCC decided to include a special report on climate change and cities in the AR7 cycle. A “cities and climate change science conference” was held in Edmonton, Canada, in March 2018 to “inspire the next frontier of research focused on the science of cities and climate change”.

The comments submitted by member countries suggest that “nearly all countries supported the idea of additional products in the seventh assessment cycle, such as special reports, technical papers or methodology reports”, the IPCC says. It adds that countries suggested a total of 28 different topics, with special reports on tipping points, adaptation, and loss and damage receiving the most support.

However, some countries had expressed concern that the three special reports included in AR6 involved a “substantial amount of work”. Some suggested that only two special reports should be produced in AR7 – including the report on cities – to “avoid overburdening the authors”.

At last week’s meeting in Istanbul, delegates decided to stick with just the already agreed special report on climate change and cities.

Despite the focus on tipping points before the meeting, the view that emerged during discussions in Turkey was that “if there were to be a second special report…it has to have a sufficiently comprehensive character that it would be useful for the second global stocktake”, Skea explains to Carbon Brief.

Several governments mentioned that a second special report “should provide guidance or evidence on climate action”, says Skea, “which a tipping points report would not” because it would be focusing on “yet another reason for acting urgently, whereas a lot of governments were looking for guidance on how to take urgent action”.

Similarly, while there was “a big push for adaptation from some governments as the subject of the second special report” at the meeting, says Skea, “a lot of the arguments were ‘well, that’s WG2’s job anyway to produce an impacts, adaptation and vulnerability report’ – hence, it would be a duplicative effort”.

Overall, the deliberations in Turkey “went much more towards the accelerated working group reports rather than the second special report option”, Skea says.

However, this logic has not been universally welcomed. Prof Lisa Schipper – a professor of development geography at the University of Bonn and AR6 coordinating lead author – tells Carbon Brief that “the fact that none of the additional special reports was agreed is not good”.

She notes that special reports can “take a lot of time and energy away” from the IPCC’s Technical Support Units and authors. However, she adds:

“A series of special reports instead of a series of working group reports before 2029 would have allowed for this science to be more regularly assessed, and for countries to have continuous input for decision-making. When the assessment is put off to 2029, this also means that governments’ attention is delayed until then.”

Dr Céline Guivarch is a professor at Ecole des Ponts ParisTech and was a lead author on AR6. She tells Carbon Brief that the decision on special reports “was probably to be expected”. However, she adds:

“It is a very concerning sign because special reports are important to give faster assessments and to cover topics in more integrated ways than the WG1, WG2 and WG3 ‘siloes’.”

What other reports will AR7 include?

As well as working group reports and special reports, there are a range of other products that the IPCC can produce.

At the 49th session in May 2019, it was decided that the IPCC Task Force on National Greenhouse Gas Inventories (TFI) should produce a methodology report on short-lived climate forcers. Short-lived climate forcers, such as methane and black carbon, are gases and particulates that cause global warming, but typically only stay in the atmosphere for less than two decades.

Ahead of last week’s meeting in Turkey, around half of IPCC member countries had indicated that they want an “additional product” from the TFI. By far the most sought-after product was on carbon dioxide removal and carbon capture and storage. The meeting saw the addition of a second methodology report on “carbon dioxide removal technologies, carbon capture utilisation and storage”.

In addition to the methodology reports, AR7 will also include a revision of the IPCC’s technical guidelines on impacts and adaptation, published in 1994, as well as adaptation indicators, metrics and guidelines. This will be “developed in conjunction with the WG2 report and published as a separate product”.

The ENB notes that the revision was proposed by India and supported by Saudi Arabia. It adds that Kenya, South Africa, Azerbaijan, Chile, Brazil, Argentina and Uruguay “acknowledged this as a good compromise, given the lack of consensus for a special report” on adaptation.

Dr Chandni Singh, senior researcher at the School of Environment and Sustainability at the Indian Institute for Human Settlements and IPCC AR6 author, says this is “very welcome”. She tells Carbon Brief:

“There is a bewildering range of frameworks being suggested and applied to track and monitor adaptation progress, and the policy salience is pressing, with discussions for the global goal on adaptation ongoing.”

What is the timeline for producing these reports?

The delegates also used the meeting to begin discussing the timeline for the upcoming AR7 cycle. In a press release, Skea stressed the importance of “getting policy-relevant, timely and actionable scientific information as soon as possible and providing input to the 2028 second global stocktake”.

However, a full timeline for the AR7 cycle was not agreed at the meeting in Turkey. The dates for the working group reports will be developed by the IPCC bureau and presented at the next meeting in late July or early August for a decision.

The ENB reports that while most countries “broadly agreed on the need to ensure that a balanced set of scientific inputs, covering both mitigation and adaptation, would be available in time for the second global stocktake in 2028, a few countries strenuously objected”. It adds:

“Until late on the final day of the session, governments’ positions were converging towards having the three working group assessment reports completed by 2028, or at least ‘striving’ to have them completed. Still, the small number of delegates who opposed this timeline held fast.”

One person present at the meeting tells Carbon Brief that “most of the resistance about the 2028 timeline came from Saudi Arabia, China and India”. This “seems politically motivated given the political position of these countries regarding climate mitigation”, they add.

The ENB reports that Saudi Arabia “opposed the shorter timeline, saying this would lead to compromised working groups reports both in content and inclusivity”. It also reports that China “emphasised that AR7 aims to be inclusive and developing country scientists should be given time to make their contributions”, adding:

“Noting the heavy burden on government officials from developing countries in AR6, China cautioned against doing work in AR7 ‘in a hurry’ and emphasised ‘that completing the WG reports in 2028 is impossible’.”

India “flagged their preference for a longer timeline, urging the chair to not predetermine 2028 as end point for AR7”, the ENB says.

Delegates did agree on a timeline for some of the reports, the ENB notes:

- The special report on climate change and cities will be published in “early 2027”.

- The methodology report on short-lived climate forcers will be published “by 2027”.

- The TFI will hold an expert meeting on carbon dioxide removal technologies, carbon capture utilisation and storage, and provide a methodology report on these “by the end of 2027”.

(Some of the IPCC documents published ahead of the meeting report that author selections for the special report on cities are already underway. More than 1,200 experts were nominated and the IPCC bureau is currently working to pare down the list to around 100 people. The list is expected to be finalised by the end of January, when the chosen experts will be invited to an initial scoping meeting, which will be held in April in Riga, Latvia.)

In addition, the IPCC says that the synthesis report – the final product of the AR7 cycle – will be “released by late 2029”.

If governments do agree that all working group reports are ready in time for the second global stocktake, the timeline for the WG1 report, in particular, will be “very time-constrained”, says Rogelj, as it would need to “conclude around late 2027”. He explains:

“Otherwise, there will be insufficient time available for the two other working group reports to go through final review and approval in time for the global stocktake. For the research and climate modelling community, this also means a literature cut-off earlier in 2027 leaving very little time for new coupled climate model runs.”

However, Prof Roberto Sánchez-Rodríguez, a professor in the department of urban and environmental studies at the College of the Northern Border in Mexico and IPCC vice chair for WG2 during AR6, says that even this timetable “fails to recognise the severity of the climate crisis and the pace of change in socioeconomic and geopolitical conditions in the world”. He tells Carbon Brief:

“Waiting until 2028 for the three reports and 2029 for the synthesis is too late to have an impact on decision-making. The world will be significantly different by then.”

Schipper says that getting the reports out before 2030 is important, as 2030 is a “mental tipping point for many”. She adds:

“The IPCC special report on 1.5°C said that we needed to be well on our way with action to stay below 1.5 by 2030 – and, clearly, we are not.”

This story was published with permission from Carbon Brief.