Got a problem with plastic pollution? Ban plastic bags. Road congestion? Introduce car-free days. Dirty streets? Fine litterbugs.

To continue reading, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

Policymakers might think that the only way to encourage citizens to lead more environmentally responsible lifestyles is to give them no choice.

But Danish behavioural scientist Andreas Maaløe Jespersen believes that giving people options rather than forcing the issue is the most effective way to change behaviour. All that’s needed is a clever nudge in the right direction.

Speaking at the recent Singapore-Denmark Climate Change Dialogue earlier this month, Jespersen, who runs the consultancy iNudgeYou, argued that nudges—subtle visual cues that work by tapping into the subconscious—can move environmentally responsible citizens from a minority to the majority without removing their freedom of choice.

A drawing of a housefly on a men’s public urinal to encourage better aiming, and yellow boxes in public spaces to show where people can smoke are classic nudges.

Similar persuasive techniques, rather than coersion will help to create more sustainable societies, said Jespersen.

“If we want renewable energy, we need people to demand it,” he told the audience at the Singapore Sustainability Academy on 11 September. “We need to convince people to move out of cars and onto bicycles, we cannot force them to.”

Green nudges

Government regulations are often complicated and technical, and even if they work to begin with, people lose the will to follow them after a while, said Jespersen. However, nudges offer a subliminal alternative to rules, taxes or incentives, he said. They work without people realising it, and do not interfere with their busy lives.

One example is Denmark’s psychological war on litter. The incidence of littering on the streets of Copenhagen, the Danish capital, was cut in half in 2011 after researchers led by Pelle G. Hansen from Roskilde University painted bright green footprints from the pavement leading to public rubbish bins.

Rather than fining people for littering—which is labour intensive and expensive, and must be done frequently and ubiquitously to alter behaviour—footprints act as a visual cue for individuals to keep their city clean.

Another example of an environmental nudge is a lamp connected to the energy supply in the home. The lamp changes colour according to how much power the household uses. The effect is to curb electricity use, and encourage people to find new ways to save energy, Jespersen pointed out.

“

Everyone wants to be climate conscious, as long as they don’t have to do anything about it. We have to crack that nut somehow.

Andreas Maaløe Jespersen, co-founder, iNudgeYou

Can nudging work at scale?

But how can measures to nudge individual behaviours scale up to transform society, asked Jessica Cheam, managing director of Eco-Business, to a panel of speakers that included Morten Kabell, Copenhagen’s mayor of technical and environmental affairs, and Esther An, property firm City Development Limited’s chief sustainability officer.

One of the most effective ways is to make the green option the default one, Jespersen proposed.

The energy mix of an entire city can be steered towards renewable energy if citizens are given renewables as the default energy option by the energy provider, he said.

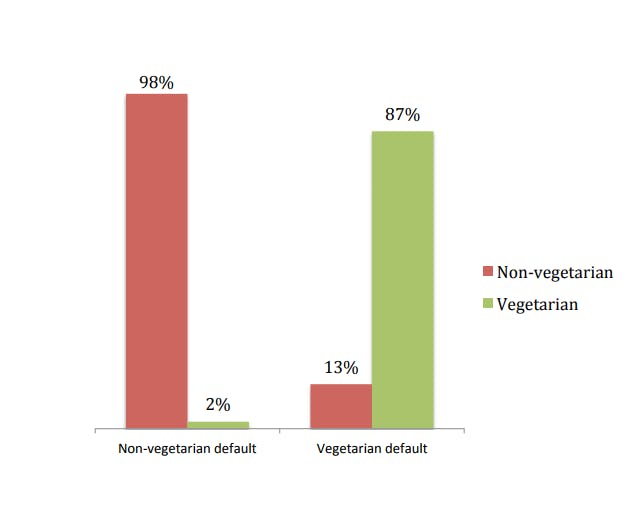

iNudgeYou’s experiment found that people are more likely to choose vegetarian food if it’s the default option in a buffet.

Even the hardest of behaviours to change, such as converting meat eaters to more climate-friendly diets, is possible if vegetarian food is made the default menu option, Jespersen argued.

An experient iNudgeYou ran found that people were far more likely to eat the vegetarian option in a buffet if vegetarian was the default option they were offered.

Does the planet have time for nudging?

But for all its potential, there is political risk associated with nudging, Kabell warned.

“A lot of comments I get from city councillors are: ‘Nudging might be cool, but will you please just implement a policy now?’” said Kabell, who was elected in 2014 on a promise to make Copenhagen a greener city.

“Politicians and planners are afraid of death by pilot,” said the mayor, who suggested that slow-moving projects are bad news for politicians who want quick results.

Another criticism of nudging is that the world is running out of time to address big global problems such as climate change in a soft, indirect ways.

To bring about change at speed, behavioural changes such as eating less meat or powering down the airconditioning are an imperative and not a choice, argued Sanjay Kuttan, an energy expert from Nanyang Technological University.

“Pilot projects show that we’re not sure [that climate change is a real danger]. But an imperative shows that we have to act now,” said Kuttan, who is programme director, Multi Energy Systems & Grids, Energy Research Institute, at NTU.

Andreas Maaløe Jespersen speaking at the Singapore Sustainability Academy. Image: Eco-Business

Jespersen countered that it is dangerous to deny people freedom of choice, as regulations and laws do, as it creates political tension.

He cited Denmark’s last election in 2015, when a newly formed green party called The Alternative campaigned for meat-free days in the public sector, and was “laughed at” by the political establishment.

Climate scientists expressed alarm at the political response to The Alternative’s idea, because the notion that a meat-free day was controversial painted a bleak outlook for achieving the more dramatic changes in behaviour needed to tackle climate change.

“Everyone wants to be climate conscious, as long as they don’t have to do anything about it,” said Jespersen. “We have to crack that nut somehow.”

“We won’t reach targets [to tackle climate change] unless people change their consumption habits in ways that are felt every day, and I don’t think the solution is a mandate. It will create incredible push back,” he said, later adding that if meat production was banned a black market would be created overnight.

Nudging the policymakers

Nudging individuals might be effective. But what about nudging policymakers?

Khoo Teng Chye, the executive director for the Centre for Liveable Cities at Singapore’s Ministry of National Development said that it is possible. While Singapore policymakers were expected to be “perfect, rational economic creatures” they are also “still human beings—so can be nudged,” he said.

A visit from Danish architect Jan Gehl has helped shape cycling infrastructure in Singapore, as has a civil service training programme that mandates civil servants to cycle, and a secret club of ministers goes cycling twice a month, said Khoo.

“If you spoke to any politician five years ago, they’d say it’s too hot to cycle in Singapore; you’d get 1,000 excuses why it wouldn’t work. Today, there’s been a complete shift. Now we’re talking about a ‘car-lite’ Singapore,” he said.

Kabell added that securing funding to install eco-friendly lighting in Copenhagen was made possible by showing the city council how much money could be saved from energy-efficient lighting, and what that money could be spent on, said Kabell.

“There is nothing more effective at persuading a politician than showing them how money that can be saved on boring issues can be spent on more interesting issues,” he said.

The political imperative

But even showing politicians the business case does not always work, Jespersen responded.

Even effective nudging solutions are often disregarded because they are counterintuitive to the way politics works, he said.

“Politicians likes big, shiny solutions. Big solutions are more appealing to politicians than implementing many small solutions to a big problem.”

But tackling sustainability issues often requires many small changes, not a single big one, said Jespersen.

“The meat consumption problem is a good example. We can’t make everyone vegetarian overnight. But we can change how people consume food in many different settings.”

“The trouble is, that’s a difficult solution to sell politically,” he said.