Efforts to tackle plastic pollution have focused on clamping down on the consumer goods firms that use and sell plastic products, such as bottled drink and snack brands, but a critical part of the plastic crisis story is being overlooked: the plastic producers themselves.

To continue reading, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

Just 20 companies that make polymers — the building blocks of plastics — account for more than half of all the single-use plastic waste that is clogging waterways and entering the ocean at a rate of a truckload every minute, and more than half of the biggest 100 plastic producers have no policies, commitments or targets to move towards a circular economy of reusing and recycling, according to a new report published on Tuesday (18 May) by Australian philanthropic organisation, Minderoo Foundation.

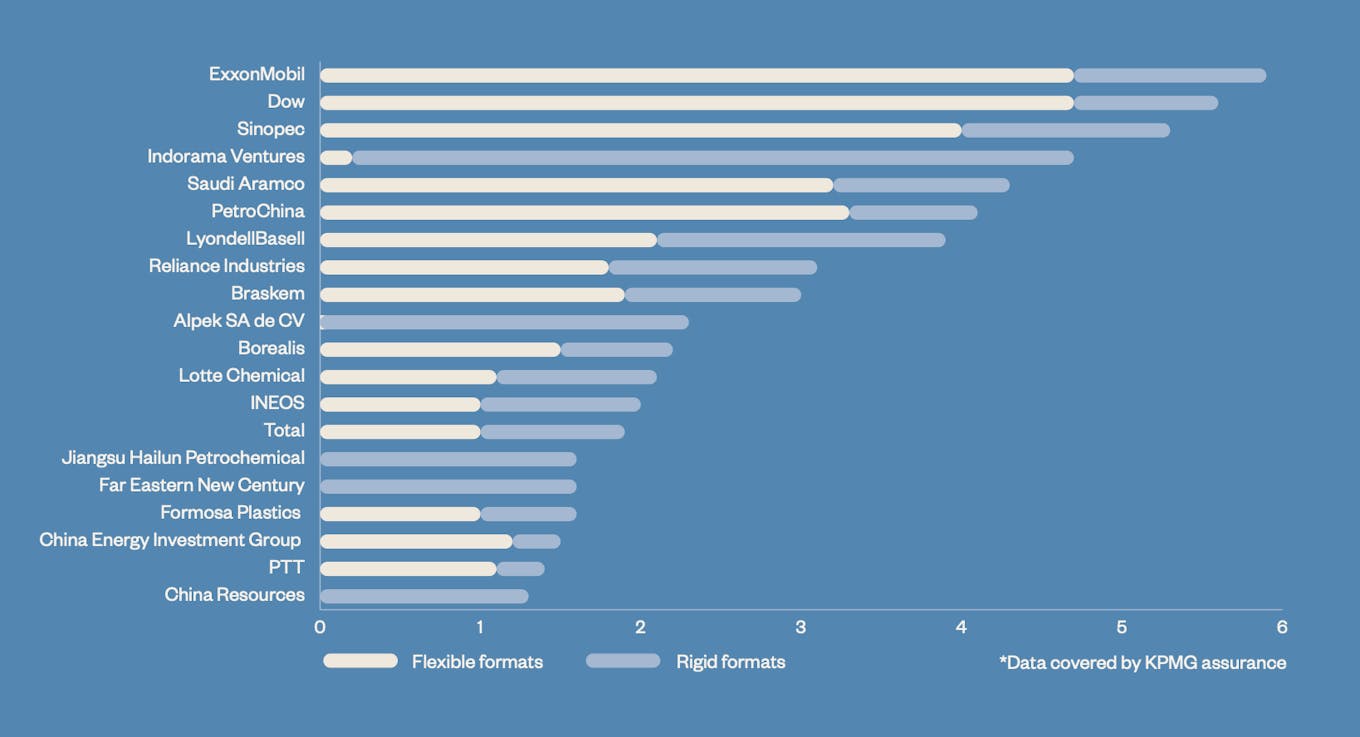

The world’s biggest single-use plastic waste producer is United States-based oil and gas giant ExxonMobil, followed by Dow, the world’s largest chemical company, and Chinese oil firm Sinopec. These three companies account for 16 per cent of single-use plastic trash globally combined.

More than half of the top 20 throwaway plastic waste generators are based in Asia, with Chinese oil giants Sinopec and PetroChina, Bangkok-headquartered polymer firm Indorama Ventures, and Indian conglomerate Reliance Industries among the 10 largest worldwide.

As pressure builds on consumer-facing businesses to reduce their plastic footprint in response to heightened awareness of the devasting effects of plastic pollution on marine ecosystems, the report — which is the first to measure the waste impact of polymer producers — notes that the world’s largest plastic producers plan to ramp up capacity rapidly in the coming years.

The makers of the biggest five primary single-use plastic polymers plan to increase capacity by 30 per cent – an additional 70 million metric tonnes – in the next five years, with 60 per cent of that growth driven by 20 producers.

The top 20 polymer producers generating single-use plastic waste, 2019, million metric tonnes. Source: The Plastic Waste-Makers Index, 2021

The bulk of these companies are oil majors banking on disposable plastic for growth in a sector projected to peak this decade. Petrochemicals, from which plastics are derived, will account for one third of growth in oil demand by 2030, and one half by 2050, overtaking oil demand from shipping, road freight and aviation, an International Energy Agency report found in 2018.

Plastic production has doubled since 2005, and is expected to grow by a further third between 2020 and 2025. The Covid-19 pandemic-induced slump in oil price has helped drive plastics production, as it is now much cheaper to produce virgin plastic than recycle used polymers. Recycled plastic or biodegradable feedstock accounts for about 2 per cent of production globally.

Over the next four years, the world will have discarded one trillion more carrier bags, one trillion one-litre drink bottles and caps, and one trillion additional metres of kitchen film, according to the report, titled The Plastic Waste-Makers Index.

If growth in throwaway plastic production continues at current rates, the material could account for 5-10 per cent of all greenhouse gas emissions by 2050.

Accountability gap

The problem with runaway plastic production volumes is exacerbated by a lack of shift towards a circular economy among the major players, the report finds. The 100 biggest producers were ranked on circularity, and more than half, including ExxonMobil and Taiwan’s Formosa Plastics Corporation, received the lowest grade possible. Thailand-based Indorama and Taiwan-based Far Eastern New Century fared best, but still only scored an average ‘C’ grade.

A lack of disclosure requirements for producers has meant that governments lack visibility of material and financial flows through the supply chain, which has hamstrung policymaking to manage production volumes and waste, the report notes.

The report’s authors, which includes experts from energy research consultancy Wood MacKenzie and non-profit think tank Planet Tracker, urge chemical companies to disclose their waste footprint, and sign up for the Ellen MacArthur Foundation’s Circulytics circularity measurement tool to assess their progress towards circular production.

Ultimately, producers need to shift their expertise and investment from producing fossil fuel-based polymers and pivot towards recycled plastic waste or bio-based feedstocks, the report suggests.

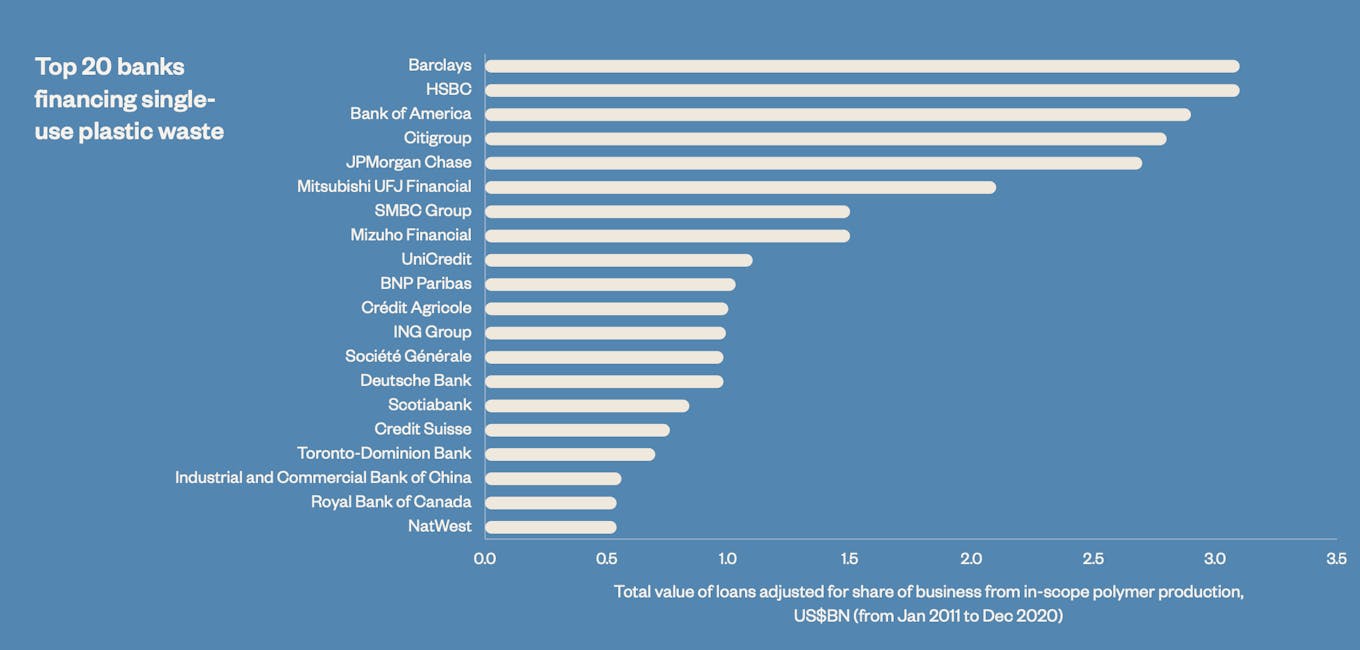

It also calls on banks and investors to shift capital from single-use plastic production towards the reuse and recycle economy; currently, the finance world provides about 100 times more capital for virgin plastic production than the circular economy.

The top 20 banks financing single-use plastic production. Source: The Plastic Waste-Makers Index

Pollution by geography

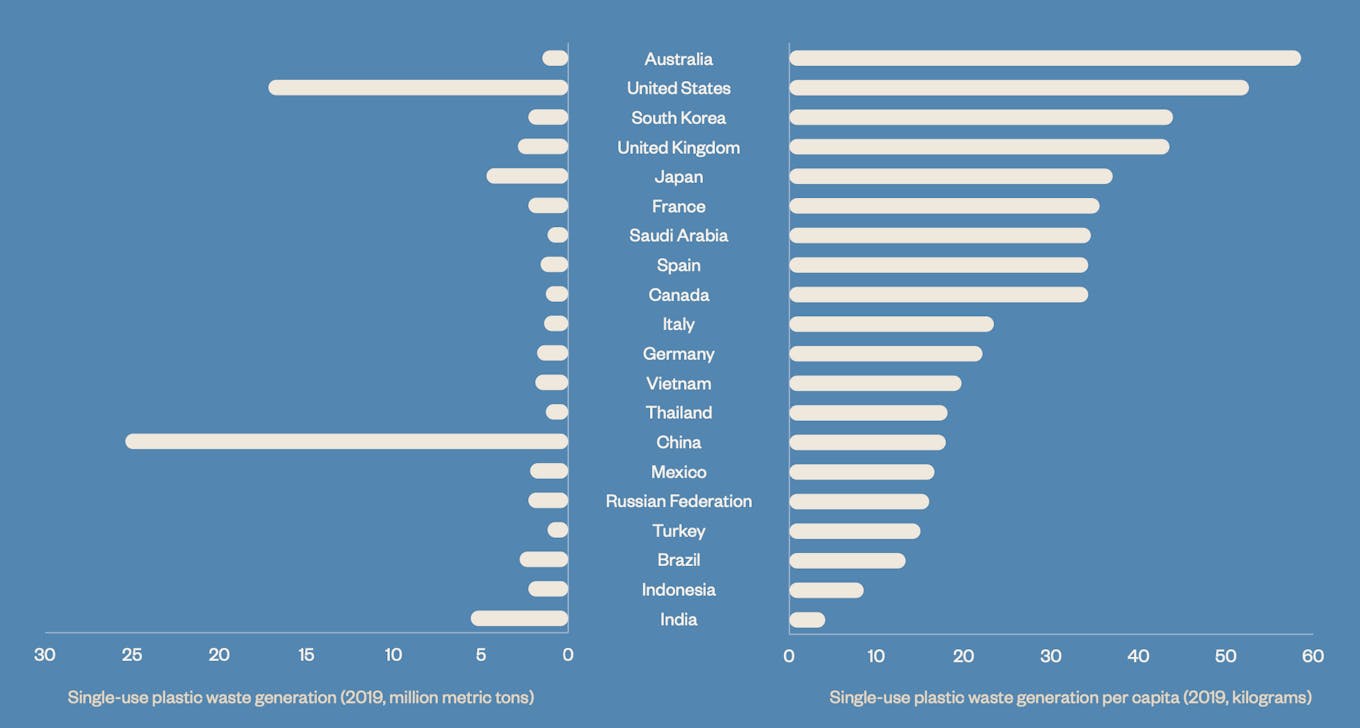

The report highlights the global nature of plastic production and consumption, noting that roughly half of all the single-use polymers produced were exported from their host countries. The five biggest exporting countries are Saudi Arabia, the United States, South Korea, Belgium and Germany.

Meanwhile, the world’s biggest net importers of single-use plastic are lower income countries, which are often lacking in waste management infrastructure to sort and dispose of cheap polymers made overseas. The report notes that China, which is the world’s largest single-use plastic producer by volume, produces 18kg of plastic waste per person per year, while the average American produces about 60 kg per person per year.

The top 20 countries generating single-use plastic waste ranked by per capita consumption. Australia, United States, South Korea, United Kingdom and Japan, respectively produce the greatest amounts of single-use plastic waste per head of pollution. Source: The Plastic Waste-Makers Index

The equivalent of a Montreal Protocol or Paris Agreement for plastic pollution is needed to address a rapidly unfolding crisis, and the uneven nature of plastic production and consumption, the report notes. More than two-thirds of members to the United Nations have shown interest is forging such a treaty, but progress has been likened to where climate negotiations were in 1992, at the time of the failed Rio Earth Summit.

“Waiting a further 20 years for an effective agreement [on plastic] would spell a disaster for the environment and our health,” the report notes.