Large companies trading in timber and other wood products meet just one quarter, on average, of the 22 best practice indicators for deforestation and biodiversity, according to the latest report published by the Sustainability Policy Transparency Toolkit (SPOTT) — a corporate transparency initiative launched in 2014 by the Zoological Society of London (ZSL).

SPOTT publishes annual assessments for the 100 most significant companies trading in a particular forest commodity, such as timber, rubber, and palm oil. Each company’s policies are scored according to 175 environmental, social, and governance indicators, making the report “the first step in a robust due diligence process for anyone sourcing tropical timber or palm oil to have a clear idea of which companies have a good commitment in place,” said Charlie Hammans, Forestry Technical Advisor at SPOTT.

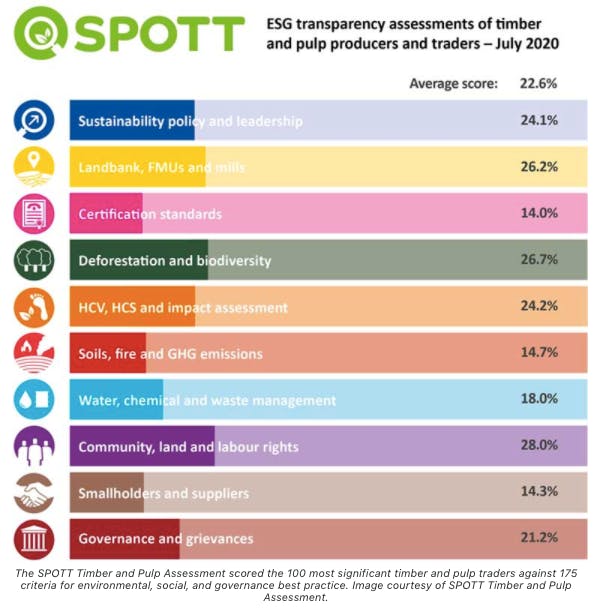

Companies assessed in the 2020 Timber and Pulp Assessment received an average score across all indicators of 22.6 per cent — up 2.2 per cent from 2019, despite more stringent criteria this year. Companies met an average of just 26.7 per cent of indicators in the deforestation and biodiversity category, but one criterion — commitment to zero conversion of natural forests — was achieved by 56 per cent of firms.

Gap between policy and practice

Around one third of companies had a clear and comprehensive sustainability policy, but just 12 per cent extended that policy to all their suppliers. Only 15 per cent have procedures to trace raw materials to the Forest Management Unit (FMU) of origin.

More than half of companies surveyed said they were committed to respecting the rights of local communities, but only 9 per cent have published procedures for obtaining free, prior informed consent from local communities on all new developments, and only eleven companies provided evidence that they are paying all workers minimum wage.

“Reports like this one help to increase the accountability of the most influential companies and increase the pressure on them to improve their sustainability policies and practices,” said Sarah Rogerson, lead researcher on Global Canopy’s Forest 500 project, who was not involved in the report.

This year is the first way-point towards the important 2014 New York Declaration on Forests’ goal of eliminating natural forest loss by 2030, making it “a pivotal year for tropical forestry,” said Hammans. But “despite the aim to have halved deforestation by 2020, forty companies out of those we researched … still don’t have a robust commitment to reducing deforestation or conversion of natural ecosystems in the supply chains.”

“The latest SPOTT report has highlighted the lack of forest protection in the largest timber and paper companies,” agreed Rogerson. “A key point is also the lack of reporting on implementation or evidence of protection even from those that do have commitments.” Only 12 of the 50 companies with zero deforestation commitments have implemented a system to monitor deforestation, and just nine have published deforestation figures in the last two years.

These results are particularly concerning, says Hammans, because of the importance of tropical forests for biodiversity. Only 46 per cent of firms had clear policies on biodiversity conservation, and “only 13 per cent of the companies we assessed are reporting putting into practice any kind of active management,” such as restoring degraded forests or rivers.

Upping the standards

SPOTT’s 2020 report added new criteria to those used in 2019 to account for practice as well as policy, and offered points for companies that walked “the extra mile of external verification of some of their policies,” said Hammans. For example, companies earned extra points for criteria verified under certification from the Forest Stewardship Council (FSC) or the Programme for the Endorsement of Forest Certification (PEFC).

FSC certification was established in 1994 and by 2020 more than 210 million hectares (roughly 811,000 square miles) of forest worldwide had received the council’s coveted international certification. PEFC’s complementary scheme, established in 1999, has certified almost 320 million hectares (1.2 million square miles) of forest worldwide through endorsement of national certification systems “tailored to the political, economic, social, environmental and cultural realities of the respective countries,” while also meeting internationally-accepted requirements, said Thorsten Arndt, PEFC’s head of communications.

In this year’s SPOTT report, average scores were lower for indicators of practice (19.5 per cent) than policy (25.3 per cent), a somewhat predictable result, given the time it takes to implement policy across tens, or even hundreds, of suppliers and millions of hectares of forestland, plus the fact that some companies may be impeded by a lack of technical capacity and the expense of hiring external consultants.

Not to mention those (hopefully few) nefarious players for whom high-scoring policies are merely a PR exercise. SPOTT’s new criteria for 2020 offer an extra level of detail to understand how the biggest suppliers are conducting themselves around the world.

A key finding: the relationship between large timber companies and their suppliers was one of the weakest areas in this year’s report card. A mere 15 per cent of the 100 large companies have policies to support contracted smallholders, and only 20 per cent said they discuss legal requirements and company policy compliance with their suppliers.

These results are particularly disconcerting, said Ardnt, “given the importance of smallholders in tropical countries in reducing deforestation and forest degradation through sustainable forest management on the one hand, and the importance of forestry for their livelihoods on the other hand.”

Some companies in the SPOTT-light

Despite the challenge of stricter rules, just under half of companies assessed still saw their scores rise relative to 2019. “Companies that have increased despite the changes should be celebrated as making true improvements,” said Rogerson.

For example, Swiss timber company Precious Woods, which manages 1.1 million hectares (around 4,250 square miles) of FSC- and PEFC-certified forest concessions in Amazonas state, Brazil and Ogoouée-Lolo and Haut-Ogooué provinces, Gabon, ranked second in the 2020 SPOTT report with a score of 89 per cent — up 12 per cent from 2019.

“The publication of Precious Woods’ first Sustainability and Transparency Report,” along with better communication of existing practices, were “key to improving our scoring,” according to Markus Pfannkuch, technical consultant at Precious Woods.

The company has a commitment to zero deforestation and an established plan to report it, and has conducted assessments of conservation value, social and environmental impacts. Furthermore, camera-traps have demonstrated that their sustainably-managed forest concessions in Gabon are providing a refuge for local biodiversity, including the elusive African golden cat (Profelis aurata).

Although there is still room for improvement among top-ranking companies, Arndt suggests, “working with currently uncertified companies and getting them to adopt sustainable forest management and sustainable sourcing practices may have a much bigger impact on the ground.”

SPOTT offered companies the opportunity to engage actively in their assessments and consultations with these firms during the process in some cases directly led to proactive improvements in policy and practice, according to Hammans. The positive impact of this engagement is evident in the final scorecards — engaged companies made up 19 out of the 21 highest-scoring firms.

Yet, despite engaging with SPOTT, paper giants Asia Pulp & Paper (APP) and Asia Pacific Resources International Holdings Limited (APRIL) saw their scores drop this year, by 4.5 per cent and 10.7 per cent, respectively. This decline was driven, in part, by substantially reduced scores in the deforestation and biodiversity category.

Both companies have been embroiled in controversy for years over their logging concessions in Indonesia, which, despite pledges to improve, have been linked to destructive practices including deforestation, burning and draining high-carbon peatlands, as well as inadequate fire-prevention policies, conflict with local communities and attempts to conceal ownership of the offending concessions.

Engaging in the SPOTT assessments has been “a positive and constructive process for APRIL,” according to Charles Paul Hogan, Head of International Communications at the APRIL Group. “We have welcomed the addition of new indicators and the evolution of the scoring methodology, even though this has affected our rating,” he said. “What’s more important is the way the process has helped us to address the gaps in transparency or fill in gaps in our sustainability policy where these have been identified.”

Hogan added that the company also works with the Carbon Disclosure Project (CDP) and professional services network KPMG to conduct environmental impact assessments and review the implementation of APRIL’s sustainability policy commitments.

Asia Pulp & Paper did not respond to Mongabay’s request for comment.

Climate change risk is “optional extra”

The report found that just 12 per cent of the big timber and pulp companies have made time-limited commitments to reduce their greenhouse gas emissions, and a mere 4 per cent have assessed future climate risk. Hammans explains why: climate change risk assessments are not a requirement for FSC or PEFC certification, so such evaluations are often viewed by companies as an “optional extra.”

Furthermore, the financial incentives to conduct costly environmental, biodiversity and climate assessments, beyond certification requirements, are often lacking.

“Climate change risk assessments are predominantly being pushed by the financial sector,” explained Oliver Cupit, SPOTT’s business and biodiversity manager. The financial sector has a well-established framework for climate change assessments because of the financial risk posed by the impacts of a warming climate, which, understandably, “investors are quite interested and worried about,” he said. However, widespread private financing in the timber sector means “it’s a lot more opaque as an industry to see who’s investing in where.”

Moving toward greater transparency

For consumers wanting to support sustainable wood and paper producers, Cupit accepts that available data “can seem a bit impenetrable… but most people do also have a pension scheme and investments in different organizations,” which can be a good place to start. There are more and more ethical investment options available, he says, but “it can still be quite bamboozling.”

SPOTT’s online platform offers a free tool for investors, asset managers and financial institutions to encourage the companies they invest in to improve their sustainability credentials, so that “consumers almost don’t have to make that decision… because there shouldn’t be an unsustainable or risky product on the shelf,” said Cupit.

“The finance sector can and should play an important role in influencing and supporting companies to improve their practices,” said Rogerson. “Some clear leaders in this sector are appearing.”

For example, the Storebrand Group (SG) — a Norwegian financial services company specialising in long-term savings and insurance — has implemented strict deforestation policies with the companies that they invest in, and SG recently led an international group of investors to meet with Brazil’s Vice President Hamilton Mourão to put pressure on the Brazilian government to take a stricter stance on deforestation and climate change.

Experts say that socioenvironmental government policies — in both producing and importing nations — will be a crucial component required to drive large-scale improvements in sustainability and transparency in timber and paper supply chains.

For example, Hammans believes that initiatives like the EU Forest Law Enforcement, Governance and Trade (FLEGT) action plan (which has already signed Voluntary Partnership Agreements with seven countries to control, verify and license timber entering the EU) help “raise the tide” for all timber and pulp companies and are the direction of things to come.

This story was published with permission from Mongabay.com.