Malaysia’s major banks are bucking a global trend towards the decarbonisation of the finance industry by continuing to finance new coal-fired power projects in Southeast Asia, a new report has found.

To continue reading, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

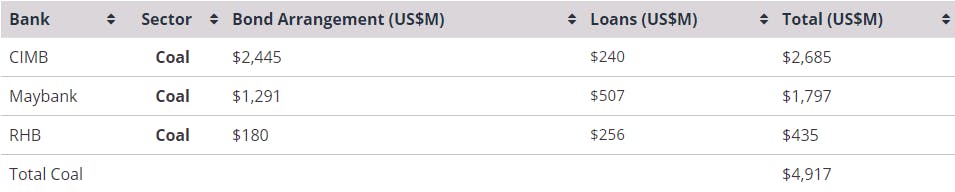

Maybank, Malaysia’s largest bank by assets and Southeast Asia’s fourth largest, CIMB and RHB Bank, Southeast Asia’s fifth and thirteenth biggest banks, respectively, have provided US$4.9 billion to coal projects in the region through loans and bonds over the last decade, data from finance-focused non-government organisation (NGO) Market Forces has shown.

CIMB is Malaysia’s biggest coal funder, pumping more than US$2.6 billion into coal projects between 1 January 2010 to 31 December 2019, while Maybank provided US$1.8 billion and RHB, US$435 million over the same time period, figures from Market Forces’ report, titled Malaysian Banks’ dirty habit, show.

And Malaysia’s banks show no sign of backing away from coal—as 45 major international banks have done, according to data from BankTrack, a civic society group that tracks finance groups’ climate policies.

Both CIMB and Maybank have expressed interest in joining the funding collective for the Jawa 9 and 10 project in Indonesia, a US$3.5 billion, 2,000 megawatt facility that is projected to kill 4,700 people prematurely from air pollution over its lifetime, the report claims.

The coal-fired power station, which is expected to be operational by 2024, will help Indonesia secure the world record for the most functioning coal plants near a capital city. The site for Jawa 9 and 10 is located in Banten, a province within 100 kilometres of Indonesia’s capital, Jakarta.

CIMB, Maybank and RHB’s coal funding activity from 2010 to 2019. Source: Market Forces/IJGlobal

In response to the report, CIMB told Eco-Business that last year the bank started to implement financing policies that “consider the ESG [environmental, social and governance] impacts of all potential clients and avoids financing of egregious environmental and human rights violators”.

“As part of our commitment to continually improve and ramp up our positive impacts, we plan to actively conduct risk assessments of our financing portfolio, including the supply chain risks we are indirectly exposed to, from 2020 onwards,” commented the bank’s head of sustainability, Luanne Sieh. She did not state that this equates to ruling out coal funding.

Maybank and RHB Bank had not responded to Eco-Business’s questions at the time of publishing.

Malaysia has one of the highest rates of per capita coal consumption in the region, and in Peninsula Malaysia about 90 per cent of energy needs are met by fossil fuels.

A 2020 report by NGO Germanwatch found that Malaysia is among Asia’s weakest performers in fighting climate change, faring worse than China, Indonesia, Thailand, and Japan, with particularly modest efforts in adopting the clean energy solutions to help the world achieve the 2030 Paris agreement climate commitments.

Malaysia’s banks have shown some commitment to renewables growth, however.

Maybank launched a US$500 million clean energy private equity fund in 2011, and CIMB has provided funding for renewables facilities in Malaysia and Thailand, set up a renewable financing package for small businesses, and has of January 2020 had allocated MYR3 billion (US$724 million) for sustainability linked loans.

As big banks quit coal, smaller ones take their place

As more major banks pull out of coal, smaller banks with less experience financing large energy projects are taking their place.

”In continuing to invest in coal when other financial institutions are abandoning it, Malaysian banks are at risk of being left to prop up a dying industry,” the Market Forces report read.

In 2018, when Standard Chartered Bank pulled out of the 1,200 megawatt Nghi Son 2 coal-fired project in Vietnam after an NGO campaign highlighted the project’s conflict with the London-headquartered bank’s climate policy, Maybank replaced it, and the deal reached financial close.

Market Forces’ report emerges 10 months after Singapore and Southeast Asia’s largest banks, DBS, OCBC and UOB, all declared that they would stop financing new coal.

“Malaysian banks cannot afford to be behind the times,” the report read. “Their current lending to coal … exposes the banks to transitional climate risk owing to international efforts to meet the goals of the Paris Climate Agreement.”

The report notes that Malaysia’s central bank, Bank Negara Malaysia, has urged banks to take action by reporting their climate risk. “However, the [Malaysian] banks do not seem to be taking steps to change their policies and practices,” the report read.