What chance do clean energy activists in Southeast Asia stand in the only part of the world where coal is gaining share in the energy mix?

Coal-fired power generation is growing faster than every other source of energy in the region, and nowhere faster than Vietnam, where coal generation is expected to increase by 544 per cent between 2014 and 2030.

In Indonesia, coal is also experiencing a growth spurt, despite a national pledge to increase its renewable energy capacity to at least 23 per cent of the energy mix by 2025 in line with the Paris Agreement.

The Philippines’ appetite for the world’s biggest source of man-made greenhouse gas emissions is predicted to overtake Indonesia’s over the next decade. By 2030, the archipelago will have the highest share of coal in Southeast Asia.

Eco-Business spoke with environmentalists on the frontline of action against fossil fuels in Indonesia, the Philippines and Vietnam and asked what it takes to champion clean energy in the world’s slowest region to adopt it.

Pushing for hydropower in Indonesia

“Some local government officials think they will make money from my projects. When they find out they won’t, it’s hard to convince them to support me. But I’m used to fighting them,” said Tri Mumpuni Iskandar said when asked what was the biggest challenge in building small hydropower plants in rural Indonesia.

Tough-talking Mumpuni is the director of the People Centered Business and Economic Institute (IBEKA), a non-government organisation that has built more than 70 small-scale hydropower plants that have provided electricity to half a million people in remote communities.

IBEKA sources funds from local and foreign donors to finance the hydropower plants.

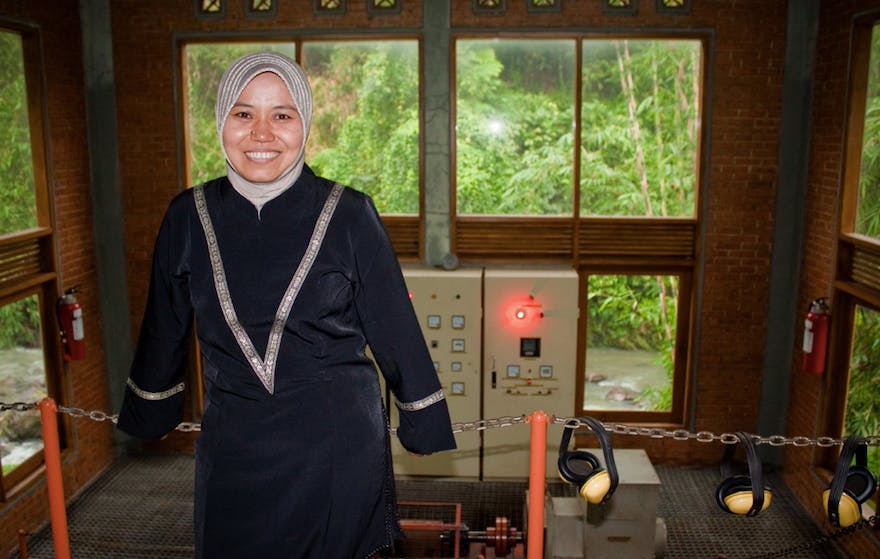

Mumpumi with a micro hydro power plant in Cinta Mekar, Indonesia. Image: IBEKA

An agricultural engineer by profession, Mumpuni has developed different micro hydropower models of varying capacity, from 5 to 250 kilowatts (kW).

One model is an isolated power-grid operated and maintained by and for the community, while another model allows for energy to be sold back to the grid.

There used to be no law that enables the national grid operator to buy electricity from independent hydropower plants, but Mumpuni has lobbied for changes in state policy.

Now, electricity may be exported and sold to Perusahaan Listrik Negara (PLN), the state-owned electricity company, generating revenue for villages to be used for development purposes, such as giving scholarships to poor families.

“

Electricity is not our main goal. It is building villages that are economically empowered.

Tri Mumpuni Iskandar, director, People Centered Business and Economic Institute

Mumpuni’s efforts made her one of six recipients of the prestigious 2011 Ramon Magsaysay Award, which honours Asians committed to public service.

In her acceptance speech, she said: “Electricity is not our main goal. It is building villages that are economically empowered. This is my highest task.”

Mumpuni’s work requires her to go to isolated parts of the country, which can be unpredictable. In 2008, Mumpuni and her husband were kidnapped in Aceh by former separatist rebels, taken to the jungle, and were forced to raise money from relatives and friends to buy their freedom.

But that experience has only strengthened her resolve to provide renewable energy in a country dependent on coal: “It was like God asking us if we were really committed to helping people. It made us braver. We still have a lot of work to do.”

A childhood passion to fight air pollution in Vietnam

As a young girl, Khanh Nguy Thi remembers how her clothes were always covered with black soot from the coal plant near her family home in Bac Am, a village in northern Vietnam.

Even worse, she witnessed firsthand how family members and neighbours developed pulmonary diseases and cancer as a result of the ash.

Her childhood experience with air pollution fuelled her passion to work on conservation issues for communities straight after college. But it was in 2011 when she set up her own non-profit that focused more on promoting sustainable energy development in Vietnam—the Green Innovation and Development Centre (GreenID).

Khanh Nguy Thi stands in front of Pha Lai Thermal Power Plant, the largest coal-fired power plant in Vietnam. Image: GreenID

It was also around this time that the Vietnamese government published the Power Development Plan, which called for 75,000 megawatts (MW) of new coal-fired power by 2030 to meet the country’s surging power demands. In a country where air pollution was already harming public health, the construction of additional coal plants would result into 25,000 premature deaths per year.

Concerned about the plan’s heavy reliance on coal and the long-term energy security and climate implications for Vietnam, Khanh decided to do extensive research into the impact of coal.

“

We should be brave and always stand with the communties we serve.

Khanh Nguy Thi, executive director and founder, Green Innovation and Development

Together with colleagues from GreenID, she produced reports that proposed reducing coal’s share of the power supply mix in favour of renewable sources in Vietnam. Their detailed examination of the expenses and risk associated with coal, along with studies conducted in communities affected by coal-related disasters, spurred public debate about the issue.

The government later announced its revised Power Development Plan in March 2016, which incorporated Khanh’s recommendation to significantly reduce the number of coal plants in the pipeline and increase renewable energy to 20 per cent of Vietnam’s total energy production by 2030.

Her efforts earned her the distinction of being one of the six winners of last year’s Goldman Environmental Prize, known as the Green Nobel prize for grassroots environmental activism.

Despite her contributions, Khanh said her advocacy has still resulted in verbal threats from some officials from the utility sector who have “vested interests” in coal production.

“Since [the distribution and sale of] power is monopolised in Vietnam, investors and service suppliers are very influential in the planning stage of selecting the technology and securing investment. [This is why] coal plants continue to be built,” Khanh told Eco-Business.

She said that clean energy activists like her “should be brave and stand with the communties we serve. Together with our communities, we know we can build better lives and a cleaner climate.”

Clean energy advocacy in the world’s most dangerous country for activists

Before he became national coordinator for one of the most vocal anti-coal advocacy groups in the Philippines, 56 year-old Ian Rivera spent much of his life as a land rights defender.

Influenced by his mother who came from a family of farmers, he was a student activist at the University of the Philippines, pushing for agricultural land rights in the early 1980s. He turned his attention to the environment when he learned that climate issues affected the use and ownership of land.

Ian Rivera in an anti-coal rally in Makati, Philippines. Image: PMCJ

In 2015, Rivera was among those who led 5,000 activists to rally against the construction of three coal power projects along Panguil Bay in Mindanao.

One of the projects was a 300-megawatt coal-fired power plant supported by the town mayor, who was rumoured to have ties with powerful private armies, including notorious kidnap gangs.

“The mayor was angered by the organisers of the rally, and we were called to his office for a dialogue in the presence of his armed bodyguards. I gathered the courage to present to him a Harvard University study on the public health impacts of burning coal and told him that his city would die and his grandchildren would suffer from air pollution,” said Rivera.

The coal plant was never constructed.

“

I have received lots of death threats. But when the climate justice movement wins over a coal plant, it’s worth it.

Ian Rivera, national coordinator, Philippine Movement for Climate Justice

Gloria Capitan, an activist who stood up against a coal power in the Philippines, was shot dead in 2016. Global Witness reported 28 environmental defender killings that year. Image: PMCJ

In 2016 Rivera joined the Philippine Movement for Climate Justice (PMCJ), a coalition of 103 groups including indigenous people, fisher folk and farmers, that campaign to tackle the climate crisis, with focus on the expansion of coal plants.

One campaign opposed the Philippines’ biggest energy distributor, Manila Electric Co, which sought power supply agreements with seven of the country’s biggest coal plants. The contract has been stalled since 2017.

Rivera said he is aware of the dangers of defending the environment in the Philippines. UK-based watchdog Global Witness recorded 30 environmental activist killings in the country in 2018, the highest death toll globally.

“I have received lots of death threats. But when the climate justice movement wins over a coal plant, it’s worth it,” he said. “We are very vulnerable to the impacts of climate change and are at the forefront of the climate justice struggle.”

Read the story in Bahasa Indonesia here.