Southeast Asia, along with Asian giants China and India, is shifting the centre of gravity of the global energy system to Asia. Its population boom, along with economic growth, is set to fuel energy demand and send it rising by 80 per cent by 2035, predicts the International Energy Agency.

Governments across the region – where a fifth of the population still lack access to energy – have been meeting rising demand primarily by increasing fossil fuel imports and investing into gas and coal power plants.

The IEA estimates that as much as 60 per cent of electricity generation growth in that same period will likely be met using coal, which is highly pollutive and generates the highest carbon emissions among the fuel sources.

This increasing reliance on fossil fuels will no doubt impose high costs on Southeast Asian nations and expose them to economic headwinds, even as it complicates their efforts to curb greenhouse gas emissions and tackle issues such as pollution and climate change.

This is why energy policy has ranked high on the agenda for the region’s governments, with many realising the potential of renewable energy to address these issues.

Apart from the region’s physical geography providing abundant renewable resources such as sun, wind, hydro and biomass, the costs of renewable energy have also reduced significantly that they are now cheaper than grid power from imported natural gas and oil.

Thanks to these developments, the region’s governments have in recent years announced ambitious renewable energy targets and introduced policies that encourage its adoption.

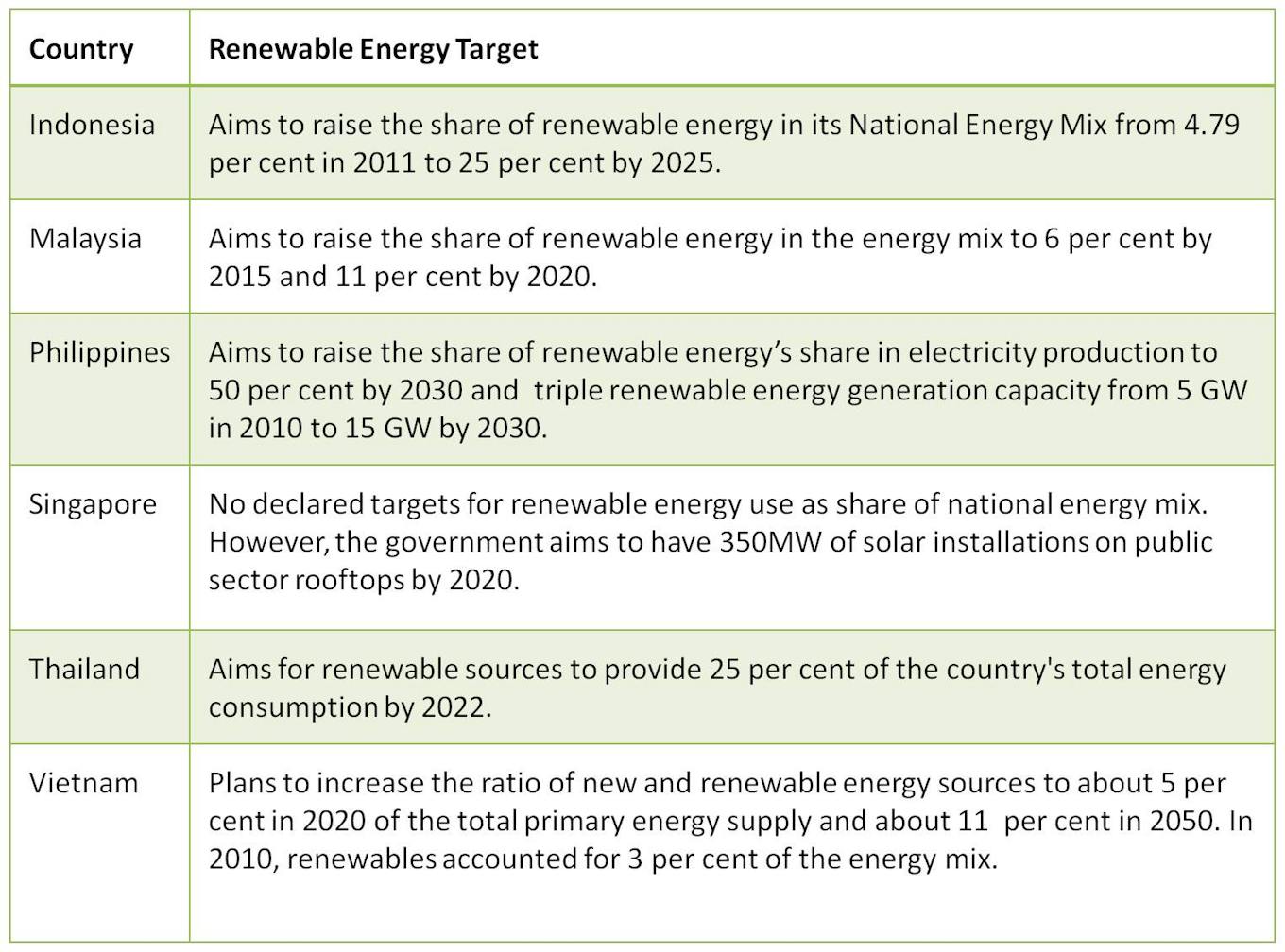

Indonesia, the region’s most populous nation, for example, aims to raise the share of renewable energy from 4.79 per cent in 2011 to 25 per cent by 2025.

Thailand has a similar ambitious target of raising renewable energy’s share to 25 per cent of total output by 2022, while the Philippines seeks to meet 50 per cent primary energy needs from renewable energy by 2030, up from 40 per cent currently.

These targets are more ambitious than those set by countries in the European Union. The United Kingdom, for instance, plans to get 15 per cent of its energy from renewable sources by 2020 and France has set its target at 23 per cent in the same time frame.

However, unlike the European Union, where each member state is legally bound to report their progress on renewable energy targets to the EU Commission, there is no central body that monitors progress in Southeast Asian countries. Industry experts familiar with these markets note that they are significantly behind schedule.

An overview of renewable energy commitments made by Southeast Asian countries. Image: Eco-Business

Falling behind

In Thailand, which aims to have 14 GW (gigawatts) of renewable energy installed by 2022, the energy ministry recently reported that only 3.78 GW had been installed by last year, leading the energy department’s director general, Viraphol Jirapraditkul to note that “we have only seven years to achieve our target, and it is time to speed it up”.

Progress has also been slow for their neighbour, Malaysia. The country’s Sustainable Energy Development Authority stated a target of 975 MW (megawatts) of energy generation of renewable sources by 2015, but at the end of last year, this stood at only 195 MW, or one per cent of its energy mix.

A separate study by the Climate Markets and Investment Association on the Philippines, which plans to triple its renewable energy capacity by 2030, found that only a tiny fraction of the additional power required (125MW out of 10 GW) has been committed to date.

The country also declared that 2,155 MW of the target must be met by 2015, which has not been the case.

“If this deployment speed prevails over the coming years, neither the 2015 milestone target, nor the 2030 target will be within reach,” the CMIA report predicted.

Andrew Affleck, founder and managing partner of clean energy investment firm Armstrong Asset Management, tells Eco-Business that while the targets were ambitious, they were not unrealistic.

Made at a time when oil prices were high, the targets “were addressing the energy realities and needs of Southeast Asian economies,” he explains.

A bumpy path to renewable energy growth

Affleck points to several factors that have impeded the growth of the renewable energy market in Southeast Asia. In the earlier years of the past decade, governments adopted a cautious approach due to the perceived high costs of renewable energy.

While the cost of renewable energy has dropped in recent years due to improved technologies and a general rise in oil prices, other challenges have emerged.

These include financing challenges, a limited talent pool in the region, and the length of time taken to get government approvals.

Like most power infrastructure, renewable energy projects require approvals from multiple government agencies for operational aspects such as land use, construction permits, social governance, and integration with the national electricity grid. The process for obtaining these can be a slow and bureaucratic process.

Frank Phuan, co-founder and director of Singapore-based solar leasing company Sunseap Leasing, for example, notes that land use is “a very sensitive issue in most countries”.

Sunseap currently has offices in Singapore, Malaysia, Australia, and Thailand and plans to expand into Indonesia and the Philippines in the next six months. The firm, among the region’s major solar players, secured $50 million in funding from investment bank Goldman Sachs last year to expand its operations.

Municipal, military, or government entities may have different plans for the land they own, which makes securing access to land for solar projects “one of the key challenges,” explains Phuan.

The company navigates these difficulties by entering into joint ventures with local partners who are familiar with the cultural and political context of these countries.

While piecing together land use and other approvals from government authorities is likely to be inherently slow, political changes in the region have not helped either, notes Affleck.

A recent report by Armstrong Asset Management found that political unrest in Thailand following the removal of former Prime Minister Yingluck Shinawatra in May 2014 caused solar project developers to delay their investment decisions. This caused a 60 per cent drop in solar project financing from 2013 to 2014.

The Thai government was also only able to meet half of a pledge they made in 2013 to install 200 MW of rooftop solar capacity by 2014.

Political upheaval in Thailand also caused a backlog of investment applications for various renewable energy and aviation, which the new military government is only just starting to clear. The country’s investment agency in February announced that it had approved applications for eleven renewable power plants, worth almost 31 billion baht (S$1.3 billion) in total.

Affleck notes that governments now need to focus on removing domestic barriers to scaling up projects such as simplifying the approval process, removing opaque licensing systems and provide grid access for private sector developers on a competitive basis.

He adds that Southeast Asian governments today have a rare window of opportunity to reduce fuel subsidies, which will remove distortions in the energy market and make renewable energy even more compelling.

A new dawn for clean energy financing

“

The will to make things work is present and roadblocks are slowly but surely being cleared. Speed, however, remains as a major obstacle to these targets being met on time.

Andrew Affleck, founder and managing director, Armstrong Asset Management

Industry observers say recent developments give them cause for optimism that the road to renewable energy could get quicker and smoother from now on.

Affleck observes that financiers are also slowly becoming more keen to invest in renewable projects, which ought to accelerate the region’s transition to a more sustainable and stable energy system.

Renewable energy projects in the region have historically found it more difficult to secure financing than traditional energy in the region, for various reasons.

In a report issued last year, International law firm DFDL attributes it to the smaller monetary value of renewable projects and the ongoing perception that renewable markets are new and unstable, and therefore, a risky investment.

Other factors include the high up-front costs for these projects, which require longer loan periods than may be available.

Investor confidence can also be undermined by a perceived lack of experienced developers and a strong talent pool to implement projects in the region, notes Affleck.

He adds that because clean energy companies tend to be smaller than traditional energy firms, they may also find it difficult to secure conventional loans. This means they are required to put up property or other assets as collateral.

But as Southeast Asia’s financial industry matures, banks in the region are slowly becoming “more open to shift away from the traditional mode of collateralised lending,” he says.

Private investors who used to consider renewables investment in Southeast Asia a high-risk venture have also had their concerns allayed by a recent slew of projects which have successfully gotten approval in the region.

In fact, Southeast Asia’s clean energy financing has grown at an eight per cent compound annual growth rate between 2010 and 2014, Armstrong Asset Management reports.

Last year, the region’s wind energy sector saw its largest ever annual investment volume, mostly due to a US$450 million investment in the Burgos wind farm, a 150 MW project in the Philippines.

Richard Tantoco, head of the Energy Development Corp which runs the Burgos wind project, noted in a statement that the Philippines’ “transparent and predictable regulatory regime” would encourage more players to pursue renewable energy investments.

International investors are also beginning to express interest in clean energy in the region.

In February, leading French solar company Urbasolar announced a 9 billion peso (S$276 million) solar project in the Philippines, financed by a consortium of European funders concerned about climate change.

Edwin Khew, chairman of the Sustainable Energy Association of Singapore (SEAS), says that in addition to the emergence of new financing models, an international shift in climate policy may also be compelling banks to invest in renewables.

As fewer power plants are built and a global agreement on climate change limits the use of fossil fuels, “banks will be forced to look at renewable projects,” says Khew.

He points to a growing number of sustainable investing policies by banks worldwide as a sign that sustainable projects will find it easier to secure financing in the future.

Clean energy companies are already seeing results of this shift. Frank Phuan of Sunseap Leasing says that the company “has never faced an issue” when dealing with banks in the countries they operate in.

The presence of feed in tariffs inspires even more confidence among banks that clean energy projects are bankable, says Phuan.

Feed-in-tariffs incentivise clean power by paying companies and households for the renewable energy they supply to the grid. They are extensively offered in the Philippines, Thailand, and Malaysia, among other regional players, but not in Singapore.

As more projects are successfully rolled out in the region, Affleck also predicts a virtuous cycle of talent development where the commercial viability of clean energy projects makes it worthwhile to invest in skills development, which in turn generates a talent pool to support industry growth.

Optimistic outlook

These changes in the way that banks, businesses, and policymakers approach renewable energy indicate that “the will to make things work is present and roadblocks are slowly but surely being cleared,” says Affleck.

“Speed, however, remains a major obstacle to these targets being met on time,” he adds, noting that decisive government action will be the catalyst that helps willing financiers and a growing talent pool move forward quickly.

Khew is also hopeful that the targets will be met in the next decade, as “these countries have their heart in the right place, and they know what they need to do.”

Countries will also pressure each other to achieve their targets, says Khew. This could be through a global legal agreement, such as the one governments are working to achieve at the UN climate change meeting in Paris in December, or by sharing expertise with one another to build capacity to drive the region’s renewable energy sector forward.

He points to the recent launch of a training centre for regional policymakers by SEAS and the Asian Development Bank (ADB) as an example of the latter. Funded by ADB, the S$1 million centre will train government officials from around the region on policy, financial, and technological issues associated with renewable energy in a bid to help countries speed up their adoption of clean energy.

“I’m hopeful that in the next 10 years, things will progress towards those targets,” he says.