The private island resort that she co-founded in 2012 had already invested in advanced water treatment systems, waste management and food composting.

The next step was to harness solar power and Cher Chua-Lassalvy of Batu Batu - Tengah Island, in Malaysia’s Johor Marine Park, was waiting for a good contact to come by.

At a Global Sustainable Tourism Council training event in Chiang Mai this year, she caught a presentation by Sujay Malve, the chief executive of Canopy Power, a three-year-old startup that has installed microgrids at several eco-resorts in Southeast Asia.

They had a drink after the training ended and the rest, as Chua-Lassalvy put it, is history.

Solar energy will supply about 30 per cent of Batu Batu’s energy needs when the photovoltaic-storage hybrid system is set up, and that proportion could rise further if she works with a consultant to cut energy use.

Microgrids—localised power grids that can be synced with the main grid, or be independent of it—have been touted as a way to increase renewable energy adoption, especially in regions such as Southeast Asia where power demand is soaring.

They are also a solution for communities without access to electricity or at the mercy of brownouts. The International Renewable Energy Agency estimates that 65 million people in Southeast Asia are without adequate or reliable access to electricity.

With the cost of components such as batteries and solar panels dropping, and the price of electricity generated by renewables equal or cheaper than generated by fossil fuels in recent years, microgrid projects are growing.

Last year, Solar Philippines, one of the country’s biggest solar providers, completed Southeast Asia’s largest solar-battery microgrid in Paluan town, comprising two megawatts (MW) of solar panels, two MWh of batteries and two MW of diesel backup.

In Myanmar, Yoma Micro Power has installed 51 off-grid micro power plants in rural areas and is set to deliver another 200 by the end of this year.

In January this year, Singapore-based company WEnergy Global, management consultancy ICMG Partners and investment company Greenway Grid Global formed a US$60 million investment entity that aims to finance and manage renewable energy projects in Southeast Asia. WEnergy has microgrid projects in the region.

‘Low-hanging fruit’ going mainstream

Investors are becoming more aware of microgrids and opening their wallets for projects, said Malve, who founded Canopy Power in early 2016. “That tells you microgrids are becoming more mainstream,” he said. “If you ask me, it’s a low-hanging fruit (in the fight against) climate change.”

And although the fear of technology is real among customers, they are also becoming more aware of the potential of microgrids. Three years ago, “people just didn’t know that there are solutions available. Those that knew solutions were available didn’t know who to call. And those who were ready to (adopt microgrids) didn’t have money”, said Malve.

Misool, an eco resort in Raja Ampat in Indonesia, was Canopy Power’s first client. It invested US$530,000 in a photovoltaic-storage hybrid system in 2018, which enabled renewable energy to meet 55 per cent of its needs. Work is underway to install more batteries and solar panels to boost the percentage of renewable power to about 80 per cent.

Other clients include Telunas private island in Indonesia and Wa Ale Island Resort in Myanmar. Telunas’ co-founder Mike Schubert said his team had been looking into alternative power for over a decade, but faced two obstacles. They needed a system that made financial sense—not one with a payback period of 20 years—as well as a provider that could offer monitoring and services after installation.

The renewable energy penetration rates of Canopy Power’s clients range from 30 to 85 per cent.

“Sometimes people ask, ‘Why 85 per cent, why not 100 per cent?’,” said Malve.

“To achieve the last 10 to 15 per cent, you’re always going to end up with a very large solar system and very large battery system. Imagine four or five days of rain with no sun at all—to take care of those days, you really need to have a very big battery system so the cost goes up exponentially. We take customers to a practical limit.”

The microgrids’ payback period is between three and seven years, depending on diesel cost, and the systems are expected to last 20 to 25 years. Carbon emissions drop and this is also a good marketing tool for the resorts, he said.

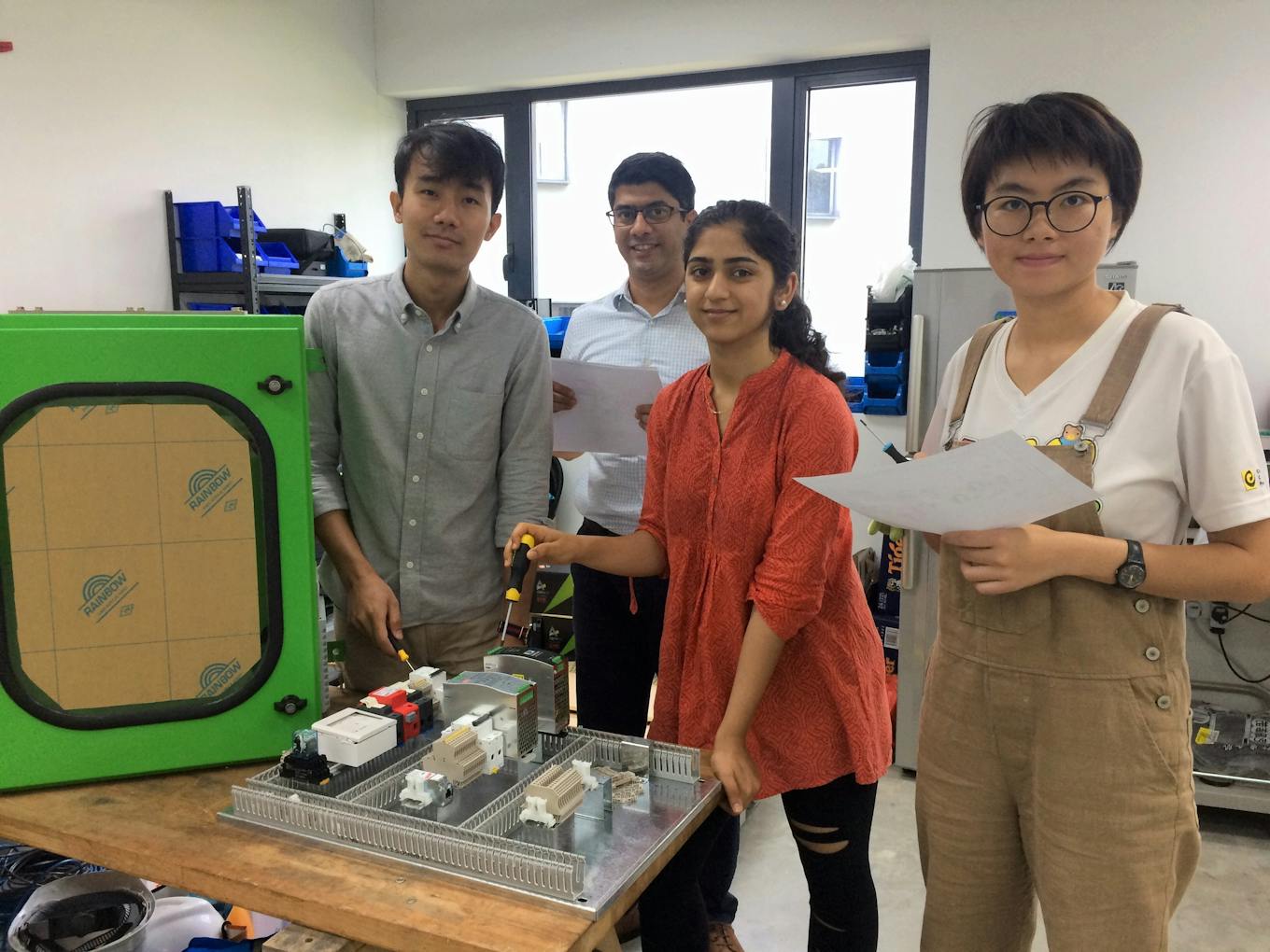

Canopy Power chief executive Sujay Malve (second from left) and some members of his team working on the Hornbill remote monitoring system. Image: Eco-Business

Microgrid projects usually take four to six months to deliver and because of the remote locations of projects, “going there is always fun”, said Malve.

Logistics can be a challenge and planning has to be perfect. Because most clients do not have moving equipment such as forklifts, his team has to pack the items and ensure they weigh no more than 200kg or 300kg, so that people on site can lift the load.

Once a microgrid is in place, the most immediate impact is the quietness of the surroundings. Diesel generators that would otherwise be running 24 hours a day are instead quiet for 12 to 18 hours. “You can hear the birds,” said Malve.

His team trains the resort’s staff in basic maintenance such as the cleaning of systems and checking of cables. With a remote monitoring platform called Hornbill, Malve is able to check the performance of his clients’ systems from his mobile phone and take preventive action before any breakdown occurs.

Bigger projects will need financing

While tourism players are Canopy Power’s first clients, the company has been getting enquiries from fisheries, plantations and other industrial customers. Such projects will be four to six times larger than a resort project, and financing will be a critical consideration, said Malve.

Canopy Power is working with a European fund to launch a product later this year that will provide financing in the form of power purchase agreements, equipment lease or a save-to-own scheme, where the system’s savings pay for itself, he said.

As for Batu Batu, its solar panels will take pride of place at the resort when the system is up, possibly by January next year. They will be placed on the roofs of its main restaurant and bar, “upfront and centre for all passing boats to view”, said Chua Lassalvy, who also founded the non-profit Tengah Island Conservation, a biodiversity management initiative that includes sea turtle conservation.

“We want to make a statement about the support for renewables,” she said. “It also helps us continue our advocacy among peers and the local and state governments to push forward agendas on sustainable tourism planning and practices, by showcasing something obviously more sustainable.”

Read the story in Bahasa Indonesia here.