The research focuses on the north Indian state of Uttarakhand, which is still reeling from the impacts of floods and landslides that struck last month.

Growing coverage of climate migration has focused mainly on where, when and how many people will migrate due to climate change in the future, while those who stay in the face of risks are often perceived as “stuck” or “left behind”.

The study, published in Climate and Development, looks at voluntary and involuntary “immobility” in a region where migration is high because of economic and aspirational reasons, as well as development disparities.

Climate change is adding to these migration pressures as subsistence agriculture grows more unstable, the study says. Respondents reported higher temperatures, erratic rainfall, reduced snowfall and crop losses.

Those that choose to stay pointed to a lack of support on how to adapt to a changing climate, including help on what crops to grow, better infrastructure and alternative employment.

The lead author tells Carbon Brief that remaining residents do not see migration as a form of adaptation, but are “wanting to stay where they are” and are “looking for information, solutions and political will, so they can stay in the places that they call home”.

However, other experts argue that the different driving forces around migration are more complex, telling Carbon Brief that very few forms of migration in the state “can be tethered solely to environmental events”.

Mountain state

Uttarakhand is a state in the Indian Himalayan region that borders China in the north and Nepal in the east. Elevations range from 190 metres to 7,816 metres, from the Sharda Sagar reservoir on the Mahakali river to the snow-clad peaks of Nanda Devi – once thought to be the tallest mountain in the world.

Uttarakhand has 10 largely rural hill districts and three urban ones. Most of the state’s growth in industry, employment, higher education and health services has been limited to the urban plains districts, sparking migration from the mountains.

Since 86 per cent of the terrain is mountainous, farmland is scarce – yet 70 per cent of the state population depends on subsistence agriculture. Soils are poor and farmers rely primarily on rainfall. Stone fruit, such as pears and apples, as well as spices, flowers and off-season vegetables are key crops in the hills, besides staple grains.

According to a 2019 assessment by the Indian Council of Agricultural Research (ICAR) on future risk and vulnerability, Uttarakhand is at “very high risk” of climate change impacts.

Between 2020 and 2049, the report projects that there will be an increase in both extreme rainfall events and drought in nearly all districts, as well as summer temperatures 4C hotter than recent decades. And rapid glacier retreat is heightening the risk of severe floods and landslide hazards.

Climate impacts – including declines in crop yields, native biodiversity and soil health – are an “additional stress” for subsistence farmers in the Himalaya, according to the study.

Migration shift

Seasonal migration from Uttarakhand has traditionally been high, both as a part of the nomadic nature of pastoral agriculture in the mountains and also to diversify livelihoods.

But this has since morphed into families being split across different locations to earn a living, followed by permanent family migration.

This rising depopulation has led to the development of so-called “ghost” villages, where the number of residents drops to barely a hundred or so – although some experts tell Carbon Brief that the term overlooks those who stay.

According to India’s 2011 census, more than 1,000 of the state’s 17,000 villages are “uninhabited”, while nearly 80 per cent have fewer than 500 people. This data is far from current: for the first time in the country’s history, the decadal census for 2021 has been delayed.

But the mass migration of people out of these ghost villages “doesn’t mean that there aren’t people here and people choosing to remain”, says Himani Upadhyay, the lead author of the new study and a researcher at the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research and PhD candidate at Humboldt University.

To understand these shifts, the researchers conducted more than 70 interviews with affected communities in Uttarakhand and experts in New Delhi to better understand the climate and socio-cultural context of the region.

The study finds that unreliable agricultural production due to climate change has led to an increase in outgoing migration.

It identifies five main factors that contribute to decisions to stay: attachment to a place; specific natural resources and other livelihood advantages; social environment; gender roles; and dependence on subsistence agriculture.

Reasons for staying

Strong emotional bonds to a place was the most-often cited reason to stay, given by more than half of the interviewees.

A clear preference for home, comfort and community – even when things are uncomfortable, and despite opportunities to leave – highlights “how immobility is rooted in personal beliefs and shaped by local factors”, the researchers point out.

Place attachment also includes a preference for the mountain environment and its better air and water quality, food and bigger living spaces. One interviewee, who had lived for three years in Delhi, told the researchers:

“People from here migrate to Delhi, where the air is so polluted that you have to wear face masks. There are mosquitoes; there is a lot of heat and noise. What kind of a life is that?”

Some interviewees highlighted a preference for a “free and independent” life in a village compared to one in a “matchbox cit[y]”, where they might be dependent on their migrant children or looked down upon.

While 95 per cent of people interviewed were involved in agriculture, the study finds that more than half of surveyed men had another occupation – unlike women, who were almost exclusively dependent on agriculture and government pensions.

For men, this additional source of income was cited as a chief reason for staying, leading the researchers to conclude that these extra income streams make them less vulnerable to climate change than women.

Climate impacts observed by study respondents include higher temperatures, erratic rainfall and reduced snowfall. Ten interviewees said they had endured crop losses because they did not have the resources to mitigate the losses. Only three respondents had access to crop insurance.

Environment and employment

The study also finds that the expectation to migrate was largely on young men. Finding work and success in cities is seen as a rite of passage and upward mobility for these men, it says.

The authors identify middle-aged and elderly people as those who are more likely to remain; however, they only conducted three interviews with people between the ages of 18 and 30, potentially skewing this result.

Some respondents told the authors they would like to stay, but that deteriorating environmental factors, such as the drying of mountain springs, would force them to migrate.

These people “did not anticipate any government or aid institutions coming to help them adapt”, Upadhyay tells Carbon Brief. She adds:

“There was this very old woman who said ‘I have to take my medicine and I don’t have any water in the house, so I have to wait till 2pm until my grandchildren will come and they can go further away to fetch me some water’…These were the people who said that ‘we want to stay because pretty soon, a time will come when we will be forced to migrate’.”

For five of the interviewees who wanted to migrate, leaving was not an option, with a lack of resources, skills and access to migrant networks holding them back.

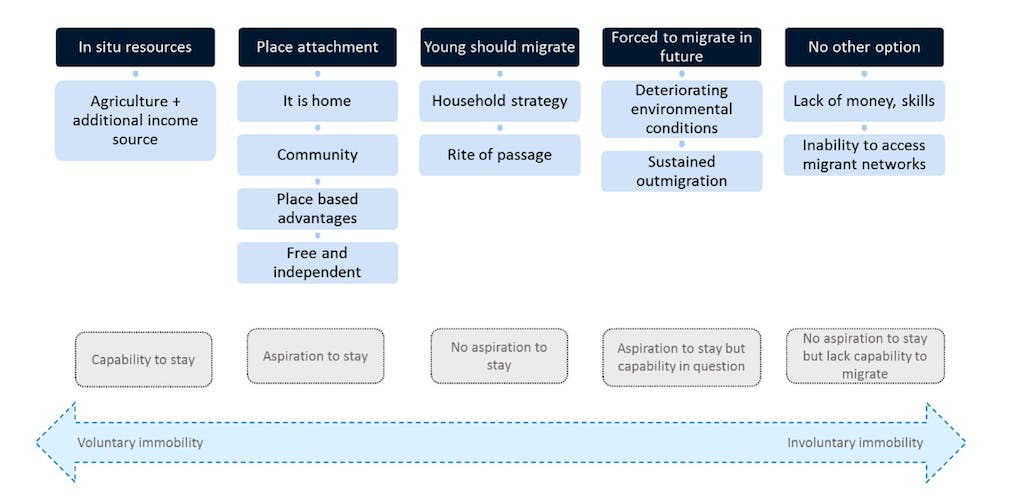

The authors identify a range of reasons for staying, shaped by an individual’s aspirations and capability. Some had the desire and means to stay, while others aspired to leave but could not afford to.

The graphic below depicts degrees of voluntary and involuntary immobility, from those with the capability to stay (left) to those who do not wish to stay but cannot leave (right).

Caption will be inserted automatically during the next time this story is saved. Alternatively you can enter caption text here or delete this caption element.

But choosing to stay does not mean someone is not vulnerable.

Interviewees who stayed were just as concerned by increasing climate impacts, declining labour availability and a lack of attention from their government. They sought support on how to adapt where they were, including information on what to grow in a changing climate, better infrastructure and alternative employment.

But, Upadhyay says, as villages began to empty, government support and presence withdrew. She tells Carbon Brief that “public institutions were shutting shop: roads were not getting fixed, no teacher” came to the village.

Limitations

The researchers admit that they could not investigate the role remittances, caste and income played in determining who stayed and why, but urge follow-up research in these areas.

Dr Ritodhi Chakraborty at the University of Canterbury, who was not involved in the study, tells Carbon Brief that while he was “happy to see more qualitative work in this space”, the study “sorely misses representing more intersectional subjects” by “relying on binary frameworks such as old and young, mobility and immobility”. It also does not reflect the variations in climate across the state, he says.

Chakraborty also says that the assessment of risk is “a little myopic”. He points out that among those who leave are “migrant men working in hellish urban heat islands in Delhi” and that it was primarily migrant workers who died inside the hydropower installations during the 2021 flood. He adds:

“This idea that somehow only rain-fed agricultural labour puts people in more risky climatic settings is not true.”

According to Chakraborty, focusing on households, instead of villages, could have made for a different analysis because “for most families, mobility of the household is critical for adaptation”.

In addition, he points out, declining village populations are not occurring just as a consequence of climate change, but also due to spatial restructuring – villages coming together to form larger villages – and land acquisition by the state, the wealthy and corporations.

To him, pahari (mountain-dwelling) women face “much greater” burdens than climate change, such as having to be both modern and traditional at the same time.

Dr Amina Maharjan of the International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development, who was also not involved in the paper, tells Carbon Brief that the study counters the “generalised” narrative that people will move when climate change impacts the habitability of their home.

Future climate migration studies, she says, should consider the well-being of migrants, migrant households and immobile populations, adding that these people “are connected and need to be studied together”.

Maharjan says that an important consideration not covered by the paper is that the lack of timely adaptation interventions will make migration a necessity. She adds:

“Once migration has started, it becomes very difficult to stop the flow, thereby bringing second generation challenges. It is of utmost importance to undertake anticipatory adaptation rather than reacting to changes.”

Upadhyay points to land ownership as a specific vulnerability for women trying to adapt to climate impacts.

”[Women] work so hard on the land, but until recently, they don’t own the land. [If] there is a disaster, then the compensation is paid to the [owner], often men.”

The authors say that their findings have wider relevance to subsistence farming communities where women and older people stay despite climate pressures.

And neither leaving nor staying is sufficient as an effective climate adaptation strategy, the authors assert. Upadhyay says:

“All this work that has been done on adaptation: what is it for, if a managed retreat or migration is the only solution [we can find]?”

”[These people] were not looking at migration as sort of an adaptation strategy. They were wanting to stay where they are and they were looking for information, solutions and political will, so they can stay in the places that they call home.”

This story was published with permission from Carbon Brief.