The tiny electric car that Chen Xianping drives to work over bumpy country roads in Shandong province says much about the hurdles facing China’s efforts to promote electric vehicles and the big car companies’ efforts to sell them.

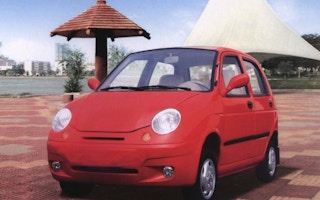

It’s not a beautiful machine. The Shifeng brand car resembles a plump Fiat Mini with oversized headlights and has a top speed of about 50 kilometres per hour.

But Chen’s little car has a big advantage: it cost only 31,600 yuan (about $5,000), far cheaper than BYD’s larger e6, which costs 369,800 yuan ($58,700). And it helps that it’s not a real car in the eyes of the government.

“I had considered getting a gasoline car, but you need to have a driver’s license and pay insurance for that,” Chen said, beaming as he drove his car home from the village school where he is a teacher.

Beijing has made a dismal start toward its ambitious goal of putting of 500, 000 hybrids and electric vehicles (EVs) on China’s roads by the end of 2015, rising to more than 5 million by 2020. Last year, a mere 8,159 were sold across the entire country, including those for government pilot programs for e-taxis and e-buses.

Although heavily subsidised, the EVs the government promotes remain expensive. Even after generous subsidies of 120,000 yuan, the price of the BYD e6 would be seven times Chen’s salary.

A dearth of charging stations and high battery prices have also contributed to the slow pace of high-performance EV sales.

But while policymakers and executives at major automakers wring their hands, scores of small, unlicenced entrepreneurs are tapping the market’s real sweet spot - not middle-class environmentalists, but lower-income buyers who want to get off their bikes and into any four-wheel vehicle they can afford.

By some estimates, some 260 million people in China still rely on bicycles and motorcycles as their main mode of transportation and could be potential customers.

“Mini electric cars are getting popular in rural areas as farmers need something affordable to carry them around,” said Wei Xueqing, vice chairman and secretary general of Shandong Automobile Manufacturers Association.

“Many are still taking their kids to school on bikes, motorcycles or even three-wheel farm vehicles, which are neither safe nor comfortable.”

Mainstream automakers, however, see it differently

“These cars are illegal, unsafe and shouldn’t be on the road,” said an executive at Changan Automobile Group, China’s fourth-largest automaker. There could also be some intellectual property rights issues, he added, and “the government should do something about it.”

Following the money

Lu Jiantong, founder and CEO of auto R&D firm Lojo EV, is typical of the small entrepreneurs who have entered the sector. He shifted his previous focus from pricey, high-performance EVs after he discovered the real opportunities for quick money were catering to rural consumers.

With Lu’s help, Yang Huayu, a Shandong entrepreneur who started building mini e-cars only a year ago, is already selling three or four a day.

“The technology must match the market. Today the high-speed electric car market hasn’t taken off yet, but demand for slow-speed electric cars is growing,” said Lu.

About 12 hours’ drive from Yang’s factory in Gaotang county is Shifeng Group’s new 480 million yuan assembly plant, where workers churn out 100 mini e-cars per day.

Shifeng is the top player in the market, with about a 50 per cent share. Shifeng delivered nearly 30,000 cars to its 200 dealer outlets across the country in 2011. Sales this year could hit 50,000, about a 13-fold increase over the level in 2008, the first full year of sales, said company vice president Lin Lianhua.

“We have a built-in capacity of 100,000 cars, we can easily speed up if needed,” said Li, who has been commuting between home and work in a blue e-car for nearly two years.

Sandwiched between the trucks, vans and farm vehicles that dominate the country roads of Shandong, the quirky mini EVs have even caught the attention of global heavyweights.

According to Wei at the automobile association, executives from Toyota Motor and Mitsubishi Motors Corp have made fact-finding trips to Shandong.

Not “green” e-cars

To expand their appeal, Lin and his team at Shifeng have started trial production of a sleeker version of mini e-cars, with improved interior design and power efficiency. Yang, the business owner, is also ready to add more factory workers to meet rising demand.

Both executives declined to share their longer-term sales targets, aware that shifting government policies could suddenly change their outlook. Like Shifeng, most of the dozens of small manufacturers in this segment operate without official licences, making their sustainability uncertain.

Moreover, the cheap lead-acid batteries that power their cars create pollution during production and disposal, hardly projecting the “green” image that government officials hope the EV sector will convey.

But they account for merely a third of mini e-car total cost, while e6’s lithium iron phosphate batteries contribute about two-thirds of the cost.

“It is definitely not a real EV. It’s future very much depends on government policy,” said Paul Gao, auto consultant at McKinsey & Co.

In late 2008, just as Shifeng was gearing up to increase output, executives got a surprise visit from Beijing regulators and were advised not to challenge the market’s status quo. Some feared the e-cars could take market share away from similarly priced low-end gasoline models.

After that visit, Shifeng’s assembly line was idled for half a year and resumed only after tenacious lobbying efforts by authorities eager to spur the local economy.

The latest message to Shandong from at least one powerful central government official: Go ahead if there is market demand, but don’t call them “green” vehicles.

Meanwhile, new orders keep coming.

Yang Wenjun, a friend of Chen’s and owner of a small grocery store in a neighbouring village, also wants to trade his motorcycle for an e-car.

“I’ve seen them around,” he says. “I figure it must feel good to visit friends and relatives in a four-wheeler.”