While conversations about Asia’s energy transition have focused on the early retirement of coal-fired power plants of late, there is a need for the first phase-out deal to get done to provide a model to follow, said Jackie Surtani, regional director of Asian Development Bank (ADB)‘s Singapore office on Wednesday (26 July).

To continue reading, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

“Too many people are talking about this. What they really need to do is to get one of these transactions done,” Surtani said.

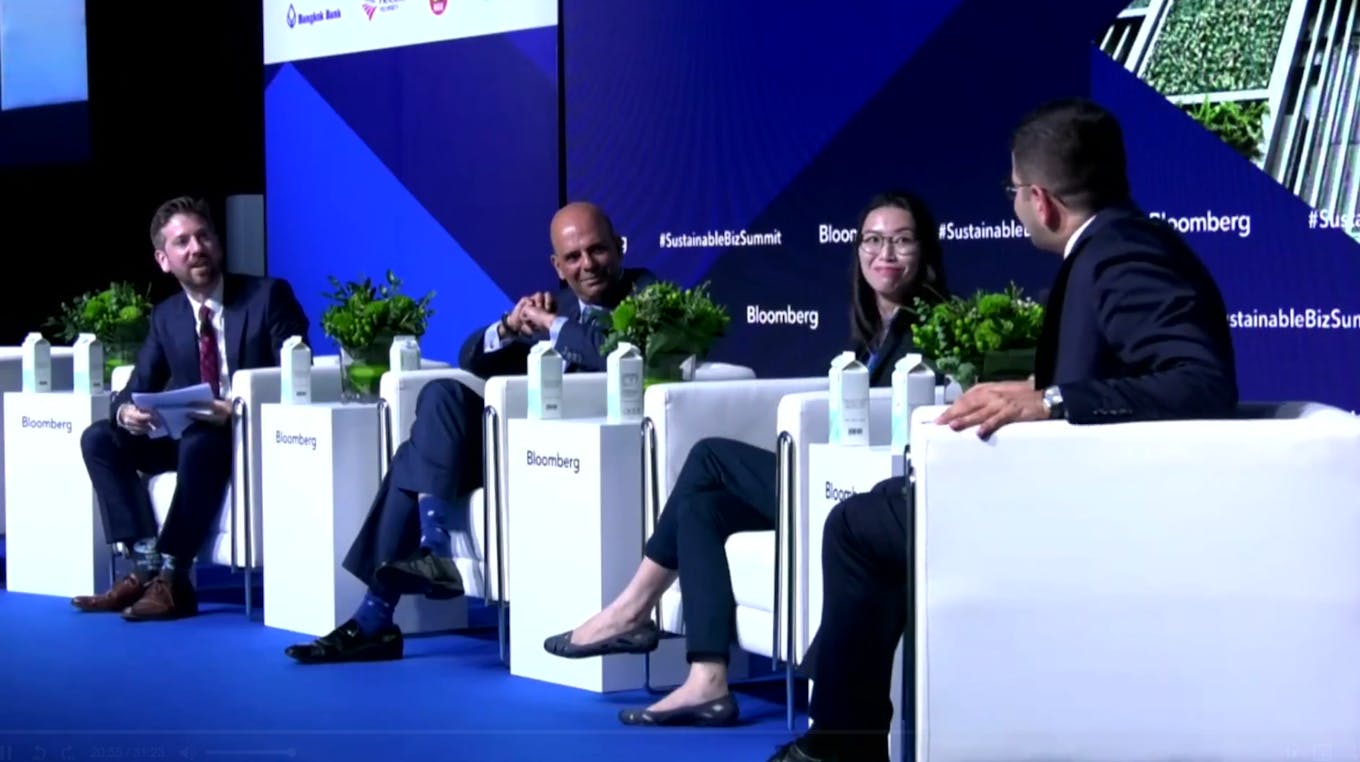

Surtani was speaking at a panel discussion on financing Asia’s energy transition at the Bloomberg Sustainable Business Summit.

In the past month, a flurry of public consultations around frameworks to finance managed coal plant phase-outs for the region have been launched by the Asia Pacific chapter of the world’s largest climate-finance coalition and Singapore’s central bank.

Yet, despite several financial mechanisms to facilitate the early closure of coal plants springing up in recent years, a successful deal has yet to be seen in the region.

A panel on financing Asia’s energy transition at the Bloomberg Sustainable Business Summit 2023. From left: Stephen Stapczynski, senior energy reporter, Bloomberg; Jackie Surtani, regional director, ADB Singapore office, Asian Development Bank; Sylvia Chen, head of ESG, South Asia, Amundi; A. Burak Dağlıoğlu, president, investment office of the presidency of the Republic of Türkiye. Image: Bloomberg Live

Trying to persuade investors to shut down coal plants before they have fully recouped their investment is not easy, said Surtani, who compared it to convincing people to leave their homes before their lease expires.

Surtani flagged that the intermittency of renewable energy and high cost of battery storage also stand in the way of the region’s immediate transition to clean energy from more carbon-intensive methods.

Until battery storage technology matures, it will be hard to ensure sufficient base load power, or the minimum amount of electricity required over the course of a day, to persuade governments to accelerate the closure of coal-fired power plants, he said.

However, Sylvia Chen, head of ESG, South Asia, for fund manager Amundi, said that renewable energy challenges have been overstated, compared to the risks around more nascent carbon abatement technologies.

While the inking of memorandum of understanding (MOU) agreements in Asia around newer technologies like carbon capture and green hydrogen is “great”, that should not be the priority, said Chen. Instead, countries “should really focus on the known technologies, which is renewables in many places.”

The race to complete Asia’s first early coal phase-out deal

ADB is currently working with Indonesia to complete its first coal retirement deal through the Energy Transition Mechanism (ETM). The multilateral development bank has done feasibility studies elsewhere in Asia Pacific, namely the Philippines, Vietnam and, more recently, India and Kazakhstan.

At full scale, the ETM is expected to retire up to 50 per cent of the coal fleet in Indonesia, the Philippines, and Vietnam over the next ten to 15 years.

Under the ADB’s initial agreement with Indonesia, the Cirebon 1 power plant would be refinanced in a US$250 to US$300 million deal on the condition that it will be retired permanently by 2037. ADB estimates that it could reduce about 30 million tonnes of greenhouse gas emissions by shortening its operating life by at least 15 years.

It remains unclear when, and whether, this deal will succeed in reaching financial close. While an MOU was signed last November, a definitive agreement which includes details about the financing package for the plant owner Cirebon Electric has not yet been reached.

“What I can tell you is that all stakeholders are working very hard towards getting this done. There’s no lack of enthusiasm. There’s no lack of very hard work. There’s been a lot of meetings in Jakarta. But these things take time,” Surtani told Eco-Business.

In response to a question on how the ADB, through the ETM project, will support the deploying of renewable energy to replace the power currently supplied by Cirebon 1, Surtani clarified that this is being treated as a separate workstream from the early phase-out of the coal plant and not included in the agreement.

Surtani emphasised that the retirement of coal-fired power plants has to happen before promoting potential competitively-priced renewable energy projects, citing the example of Java in Indonesia, which faces an oversupply of power and therefore needs to phase-out coal before increasing its renewable energy capacity.

Economics or politics?

In Indonesia, the phase-out of coal power is expected to result in 245 job losses for each coal plant on average, with knock-on impacts on upstream mining operations which currently employ 250,000 people, most of whom are low-skilled workers. In India, which has the second-largest number of coal workers worldwide after China, the livelihoods of nearly four million people are directly or indirectly linked to coal.

While the creation of more jobs associated with renewables are anticipated in the long run, a “just transition” for former workers could be challenging in the immediate term, especially if is no guarantee that new clean assets will be built near the communities most affected by coal closures.

When asked which of the two was a bigger roadblock – the economic puzzle or lack of political will – for the early retirement of coal in Asia, Surtani responded: “I will not say the economics is more important than working with the government, or working with the government is more important than the economics. You deal with everything and make sure that all interests are aligned.”

Each project and country has its own “bespoke” issues, with no “simple magical answer”, said Surtani. ADB currently works with private sector players on the Cirebon 1 project, but there might be a whole set of different issues if they were working with a state-owned utility, he said.

“We are where we are today because we are overcoming everything one step at a time, and the rest will play out. We’ll either come up with a solution, or we’ll hit a roadblock,” he said.