To represent the reality for media professionals operating in Southeast Asia, studies assessing press freedom should capture how reporting is undermined by both government and non-government entities. They should also assess other constraints such as a lack of access to information, financial precarity, and how media workers’ identities affect their work, New Naratif researchers argue in a report published last month.

To continue reading, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

A granular look at the challenges independent media workers in the region face will better secure their safety and rights, and is the first step to building regional solidarity among these often marginalised individuals.

Addressing these issues could potentially improve the coverage of underreported issues such as environmental degradation and land rights, sustainability in opaque industries, as well as human rights abuses. These areas have in the past been contentious, and often dangerous, for the media to report on.

“By way of writing, they’re trying to lift up their communities and bring to light stories of injustice,” said Sahnaz Melasandy, network coordinator and report co-author.

More than numbers

Reporters Without Borders (RSF) recorded that at least 76 journalists were imprisoned in 2021 and one was killed in Southeast Asia. The majority of countries in the region are poorly rated in its World Press Freedom Index with Brunei, Laos, Singapore and Vietnam ranking in the bottom 30 countries globally. The France-based non-governmental organisation found that Asia has some of the highest rates of abuses against journalists covering the environment.

But most global media freedom indices and reports only show a snapshot of what’s happening in the region, and do not account for the nuances within and between countries, the researchers said. “It’s important to listen to what people on the ground have to say, in addition to scholars and leaders from Western institutions,” said Fadhilah F. Primandari, democracy researcher and co-author of the report.

For example, RSF has a secretariat and council comprised mostly of European members. Its freedom index is determined through an online questionnaire of 87 questions, which is sent to media professionals, lawyers and sociologists selected by the organisation. Scores are then tabulated based on these responses combined with the data on abuses and violence against journalists—compiled by researchers and their networks of correspondents in 130 countries—during the period evaluated.

The New Naratif researchers instead conducted a qualitative analysis of 44 independent media workers, those who do not work in state-owned or state-affiliated media, from eight different countries including Malaysia, Indonesia, the Philippines, and Singapore.

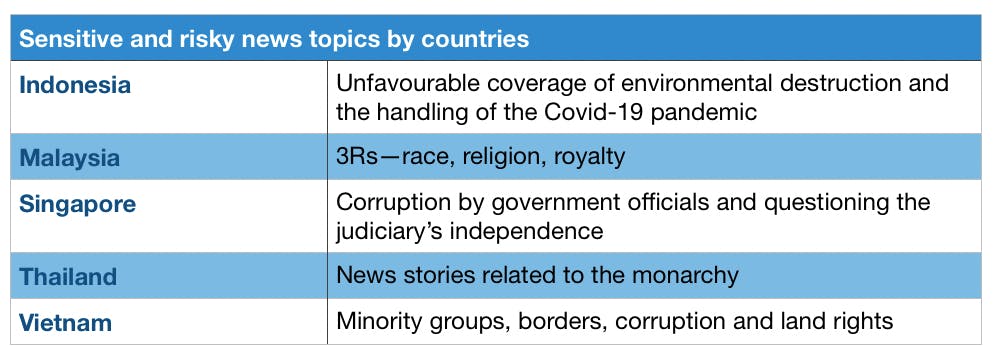

Topic sensitivities vary across geographies, the research revealed. Media workers could face physical violence and police brutality as a result of producing stories that criticise governments, prominent politicians and the military. Other more ‘passive’ but corrosive methods including regulatory harassment, restrictions and lawsuits by both governments and members of the public. Anti-media propaganda and digital attacks have also been deployed to muzzle press freedom.

Increased digitalisation has opened up a new avenue for attacks against media workers allowing the public to directly engage with the publishers and writers. Internet trolls skew online discourse through reactionary and negative comments. Doxxing—searching for and publishing private or identifying information about media workers—and hacking, are other forms of internet attacks that put their safety at risk.

Sensitive and risky news topics by countries in Southeast Asia. Source: New Naratif

Sensitive and risky news topics by countries in Southeast Asia. Source: New NaratifTo ensure that stories are fairly reported, independent media workers should be able to safely access primary sources of information and data, said Primandari. “It goes beyond looking for information online, but also being able to interview and question public officials.”

“Sometimes, government bodies might be more sceptical towards independent media, so they don’t warrant access to them. This makes it difficult for independent media to hold governments accountable,” she added.

The Covid-19 pandemic has exacerbated these challenges. In Malaysia, for example, press conferences were moved online, and only state-owned outlets were invited to participate, the report said.

Beyond government sources, independent journalists in the region also face difficulties approaching the wider public for information due to a culture of fear and intimidation. “If the wider public is fearful of speaking up, journalists are unable to uncover in-depth stories nor write critically about what’s happening in society at large,” Primandari said.

Identifying the issues impinging on media freedom in the region would help ensure that local issues are not only reported by international news houses. “We’re slowly starting to see a pivot toward Southeast Asian people taking charge of their own stories by creating these spaces themselves in the region. Local communities are writing their own stories and recovering agency over their narratives, even if there are many factors working against them,” she said.

The intersection between identities and media freedom

Current metrics fail to account for the identity markers that may prejudice a journalist’s ability to do their job. Nationality, age, gender and sexuality, class, geographical location, race, as well as employment status—play a part in how freely media professionals are able to operate in the region.

“Independent media workers tend to come from backgrounds that are often marginalised, so securing the safety of their freedom and rights is one of the most important things that we have to do,” said Hassan.

Rural media workers are more likely to be subjected to assassinations and brutality than their urban counterparts with many of the cases going unreported, the researchers found.

Female media workers face more difficulties as they may be subjected to sexual harassment and gender-based bullying from both colleagues and in the field while reporting. This, again, is a factor that varies from country to country within Southeast Asia.

The art of content-making and concealment

To remain safe, media workers have devised ways to tailor and adjust their media content.

- Altering the tone and framing of the issues being covered, for example using more conservative headlines;

- Thoroughly editing and double-checking their work to guard against accusations of defamation;

- Using creative visual metaphors;

- Reporting in English rather than local languages;

- Avoiding certain topics.

Future research and studies should be conscious of how identities shape the experiences of media workers and how certain groups are routinely silenced, marginalised, and do not have as much access to participate in such research projects, the researchers emphasised.

Creating a space for regional solidarity was important to facilitate knowledge exchange and support among media workers in a climate that is hostile towards them.

“Many of our governments are very unoriginal in their tactics to oppress media workers, so there’s potential here to be in solidarity with and learn from one another,” said Melasandy.

“This will show government and the rest of the world that Southeast Asia independent media is a force to be reckoned with, and that it can’t be squashed by individual governments,” echoed Hassan.