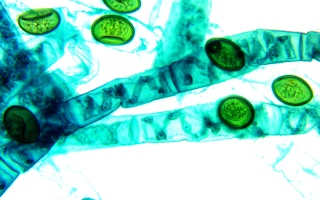

Algae—tiny organisms at the base of the food chain that pack a nutritional punch—could be the next big thing in plant-based protein, if recent developments in Singapore are any indicator.

To continue reading, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

Last month, Californian plant-based seafood company Sophie’s Kitchen won S$1 million from Temasek Foundation, a philanthropic organisation, for its plan to produce microalgae from food waste and “transform Singapore into a protein export powerhouse”.

A capsule of Simpliigood’s frozen spirulina. Image: Simpliigood

Last week, Israeli-Singapore agri-technology start-up Simpliigood Asia launched its online store selling frozen spirulina, a blue-green algae with a mild nutty taste, in Singapore. It plans to expand to the rest of the region and set up a local manufacturing facility if demand is strong.

Meanwhile, agritech firm Life3 Biotech recently partnered Temasek Polytechnic in Singapore to work at producing food-grade microalgae on a large scale in bioreactor tanks.

Proponents say algae products require a fraction of the land, water and other resources needed to produce the same amount of beef and other animal protein. This means algae can satisfy the world’s quest for a sustainable protein source, at a time when global warming is accelerating and water resources are getting scarce. The rearing of animals, such as cattle, for food is a major contributor of greenhouse gases.

Some species of algae also contain more protein than meat and are a source of micronutrients which other plant-based alternatives do not provide, they say.

The push to be cheaper than meat

The rise of algae as an alternative protein source comes in the wake of Impossible Foods and Beyond Burger launching in Singapore and other Asian cities, making waves for plant-based meat that looks, feels and tastes like real meat.

But some have noted that these alternative proteins cost significantly more than real meat, and questioned if they are healthier than the real thing. While plant-based patties may contain fibre and have protein levels comparable to meat, they may also have more sodium which, in excessive amounts, increases one’s risk of health problems like high blood pressure.

Algae producers are confident that their offerings can eventually be cheaper than meat.

“Plant-based (protein) is now more costly than meat… We want (our prices) to go below meat in the future,” said Lior Shalev, co-founder and chief executive of Simpliigood, at its launch in Singapore last week.

Shalev reckoned Simpliigood could “challenge” meat prices in the next two to three years, especially after it raises the funds for a fully automated third production line in Israel.

“

Plant-based (protein) is now more costly than meat… We want (our prices) to go below meat in the future.

Lior Shalev, co-founder and chief executive, Simpliigood

For now, the company is selling its spirulina—known as a superfood for its high vitamin and mineral content—for S$89 (US$65) for 300g and S$129 for 600g. Other possible markets in the Asia-Pacific are Thailand, the Australian cities of Sydney and Melbourne, as well as Tokyo, said Ron Snir, chief executive of Sechel Asia, an advisory and operating company in Singapore that owns half of Simpliigood Asia.

Simpliigood’s spirulina is grown in temperature-controlled farms in Israel. The company said its spirulina has three times more protein than meat, 50 times more iron than spinach, and contains potassium and antioxidants. The nutrition from 10g of its product is “comparable to an egg”, said Snir.

One of Simpliigood’s production facilities in Israel. Image: Simpliigood

Sophie’s Kitchen will produce its microalgae in fermentation tanks using food waste such as spent grains from breweries, and co-founder and chief executive Eugene Wang said it meets all of the World Health Organisation’s nutrient recommendations.

Just 0.02 hectares of land is needed to grow a tonne of his protein, compared to 141 hectares of land needed for the same amount of beef, according to Wang.

A kilogramme of the microalgae protein flour will cost US$2 over time, although initial costs will be higher, he said.

The cost of the first few batches “will not be low enough to justify retail pricing”, said Wang, who hopes to sell his first microalgae products—likely plant-based crab cake patties—within two years.

He expects to launch the first products in California as it is the “most plant-based friendly state in the United States”, but may also sell protein powder to companies making supplements in the US or Canada.

Wang said Sophie’s Kitchen has decided on partners and locations for its research laboratory and fermentation tanks in Singapore, but declined to reveal details.

Smaller footprint and waste-free?

As agricultural yields and practices come under pressure amid global warming and the need to protect forests and wildlife habitats, the companies say algae can improve food security and tackle malnutrition while incurring a much smaller environmental footprint.

Simpliigood said spirulina is waste-free as the entire biomass is consumed, while Life3 Biotech and Temasek Polytechnic aim to optimise production of high-growth microalgae with Omega 3 fatty acids to contribute to Singapore’s target of producing 30 per cent of its nutritional needs by 2030, up from less than 10 per cent currently.

There are many species of algae and Professor William Chen, Michael Fam Chair Professor and director of Nanyang Technological University’s Food Science and Technology Programme, believes the future may lie with microalgae produced through bioreactor-based fermentation.

“In general, the biomass yield from fermentation can be as much as 10 times higher than (from a) photosynthetic bioreactor, thus (resulting in) more proteins produced,” said Chen, who has given advice to Sophie’s Kitchen when approached by the start-up.

“

Most of those microalgae-for-biofuel projects were never successful. That’s why scientists started to divert their attention to foods. After all, microalgae is packed with lots of nutrients. And it is relatively easier to grow than most crops.

Eugene Wang, co-founder and chief executive, Sophie’s Kitchen

From biofuels to food

Why the growing interest in algae as a source of protein to feed the world? Wang believes it started four to five years ago when more consumers, especially in the West, started asking for plant-based protein.

“Most of the microalgae-for-food researchers I ran into were previously involved in microalgae-for-biofuel projects. Most of those projects were never successful. That’s why scientists started to divert their attention to foods. After all, microalgae is packed with lots of nutrients. And it is relatively easier to grow than most crops,” said Wang, a Taiwanese who is based in the US.

But whether algae producers can truly have impact by getting those who love their steaks and burgers to cut down on meat remains to be seen.

Consumers need to accept the colours and smells of the algae products, which vary depending on the species used, said Chen.

While it is easy to make protein powder from microalgae, it is a challenge to make microalgae flour into textured meat, he said.

Simpliigood co-founder and chief technology officer Baruch Dach said there is potential to work with food technologists, while Wang said Sophie’s Kitchen has the technology and knowhow to turn protein from microalgae into a meat-like texture.

“Plus we have access to more species of microalgae; I think you will see a lot of plant meat made from different algae from our brand in the near future,” said Wang.