Bans, taxes and polluter-pays laws are the most potent weapons available to policymakers to fight plastic pollution now.

To continue reading, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

But these three policy tools will do little to stem the tide of plastic pollution because of the sheer volume of plastic products being consumed by the world’s biggest economies, a new study by Economist Impact and Nippon Foundation suggests.

Bans on single-use plastic, levies on plastic production, and extended producer responsibility (EPR) schemes that make firms responsible for post-consumer waste are the three main policy levers that underpin a planned global treaty on plastic trash.

The United Nations-led treaty on plastic pollution, which is expected to come into force by 2024, involves 175 countries and has been billed as the most important piece of environmental legislation since the Paris climate accord.

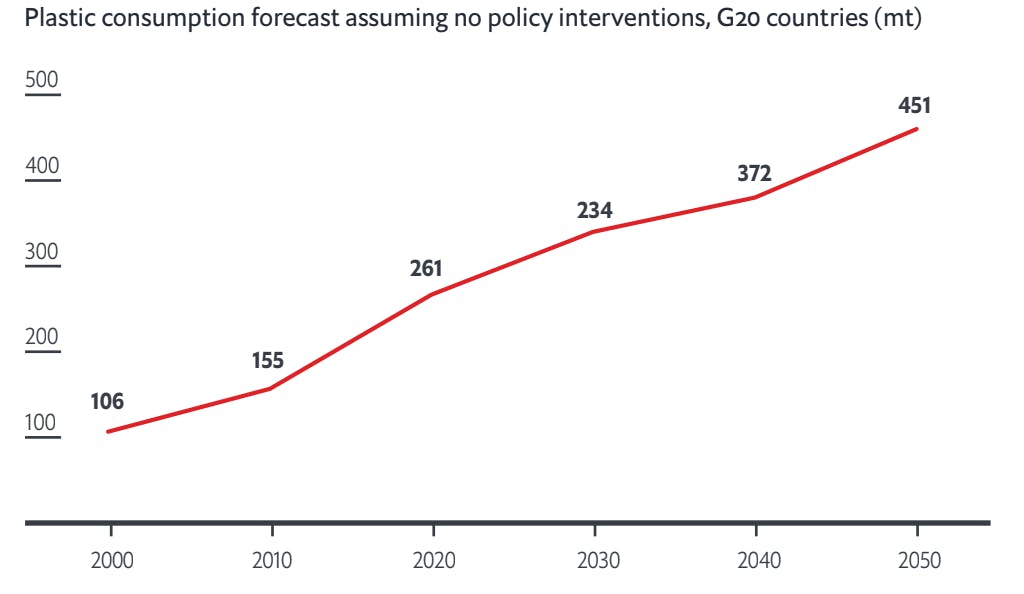

Plastic consumption forecast assuming no policy interventions in the G20, the world’s biggest 20 economies. Source: Economist Impact, 2023

But even a combination of bans, taxes and EPR laws will not cap plastic consumption, the report, titled Peak Plastics: Bending the consumption curve, predicts. With these measures in place, polymer use in G20 countries is set to rise by 1.25 times the amount currently consumed by 2050.

The report emerges two weeks after researchers found that 6 million tonnes of single-use plastic has been produced over the past two years, and a further 15 million tonnes is expected to be in circulation by 2027 as oil and gas firms pivot from oil to petrochemicals to sustain revenue growth.

The Peak Plastics study suggests that the UN treaty will be too weak to bend the plastic consumption curve downwards, and only the most aggressively applied measures will have any impact at keeping plastic use under control.

The most effective of the treaty’s proposed measures – a global ban on unnecessary single-use plastic items like straws, carrier bags and utensils – will still see plastic consumption grow by almost one and a half times current levels by 2050.

How Asia Pacifc G20 countries are curbing plastic consumption

South Korea. First in the world to ban single-use plastics; well established EPR scheme; charge US$0.01 for a plastic bag.

Australia. State-level disposable plastic bans since 2021; varied EPR schemes in place; trialled bag charges.

Japan. Law to reduce single-use plastic introduced in 2022, but promotes recycling not restrictions; established EPR scheme; charge US$0.03-0.05 for a plastic bag.

India. Ban on one-time use plastic items introduced in 2022; EPR law in pipeline; goods tax on plastic packaging and single-use products.

Indonesia. City-level plastic bans in Jakarta and Bali; EPR law in the works; US$0.03 plastic bag tax in the pipeline.

Source: Economist Impact, 2023

The approach least likely to curb consumption is producer responsibility regulations. Even if EPR schemes were mandated in the territories studied, plastic consumption is projected to be 1.66 times higher in 2050 than 2019 levels.

EPR schemes, which are well established in Japan and Korea and in the pipeline in India and Indonesia, are deemed critical for improving waste collection and recycling rates. Only 9 per cent of the 380 million tonnes of plastic produced globally every year is recycled; the rest is either burned, landfilled or leaked into the environment, the majority of which ends up in countries in the Global South with poor waste infrastructure.

A global tax on virgin plastic resin, which would address the problem of brands baulking at the relatively high prices of recycled plastic, would still see consumption rise by 1.57 times by 2050. Taxes must be aggressive to have significant impact, the study found. Countries with plastic bag taxes in place include Japan, China and India.

“On their own, these policy measures will have a marginal impact – and are not going to lead to the peak in plastic consumption we are hoping for,” said Gillian Parker, senior manager, Asia Pacific, sustainability, policy and insights, Economist Impact.

“It will take these three policy levers and a whole lot more to get a handle on the plastic waste crisis,” she said.

If nothing is done, and the UN treaty fails, plastic consumption will double by mid-century – from 261 million tonnes a year in 2019 to 451 million tonnes a year by 2050 – and will continue to rise throughout the rest of the century, the report predicts.

According to non-profit WWF there will be more plastic by weight in the ocean than fish by 2050 given the current rates of consumption. As it stands, plastic pollution costs US$100 billion a year in environmental clean-ups, ecosystem degradation, and health impacts.

Other policy measures the treaty negotiators are considering include subsidies to support plastic recycling infrastructure, standards for the amount of recycling content brands use in their products, and labelling laws that require brands to publically communicate how much recycled plastic they use in their products.

Plastic policy pitfalls

While bans, taxes and polluter-pays schemes may slow the rate of plastic consumption, these policies need to be implemented carefully with local context in mind to avoid unwanted outcomes, the report cautions.

A ban on hard-to-recycle multi-layered sachets would be welcome in most countries, as this type of packaging accounts for 80 per cent of all municipal solid waste that leaks into the environment, according to estimates by Systemiq, a consultancy.

But banning single-use sachets, which give low-income consumers in developing nations access to products in small quantities, should avoid spurring the growth of alternative disposable materials, such as paper and aluminium, which could also have unwanted environmental impacts, the study warns.

Similarly, plastic taxes should avoid making essential medical applications or packaging that extends the shelf-life of food more expensive for lower income consumers.

EPR schemes also face challenges. For such schemes to work on a global level, more harmony is needed between systems, although this is complicated by varying rubbish collection rates in poor and rich countries. The study’s authors also say that funds raised from polluters need to be reinvested into schemes that address pollution.

“The UN treaty on plastic waste could be the biggest green deal since the Paris Agreement, but hopefully it won’t give polluters as much wriggle room,” said Parker. “The study highlights the enormity of the task in negotiating the treaty, which must address the full lifecycle of plastic products to be effective.”